The Pandemic of Force: A Weilian Review of Apollo’s Arrow

Kathryn LawsonNicholas A. Christakis, Apollo’s Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way we Live, New York, Little, Brown Spark, 2020, pp. 384.

Nicholas A. Christakis’ timely meditation on the coronavirus offers the reader a thorough, engaging, and accessible look at the virus that has so long held the world in its grasp. From the history of plagues to the specifics of this particular pandemic, Christakis guides his reader through the medical, social, economic, and historical labyrinth of COVID-19. In what follows, I will offer a review of Christakis’ book that brings his ideas into conversation with the philosophy of Simone Weil.

Intimations of Plague Among the Ancient Greeks

Like Weil, Christakis sees in Homer’s Iliad a bridge to understanding our contemporary crisis and how we respond to the ordeal of death and suffering. According to Christakis, the plague of Apollo’s angry arrows in book one of the Iliad reveals our COVID-19 tribulations to be at once “wholly new and deeply ancient” (xiii). In this way, Christakis begins the book with a deep hermeneutical connection to Weil, who commonly turned to the ancient Greeks in order to understand her own tumultuous times.

When Weil famously asserts in her 1940-41 essay that the true hero of the Iliad is “force,” or that which “turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing,” she refers to war as the obvious vehicle of that force. But one can certainly see how the plague and the response to it can also be understood as a swift harbinger of force: “Exercised to the limit, it turns man into a thing in the most literal sense: it makes a corpse out of him.” The story of SARS-2 is in many ways a Weilian story of the sway of force and the limitations of necessity. For Weil, force is the movement of power and prestige that enslaves human beings, creating oppression and suffering. It operates completely in the material realm and governs the course of history. Force is limited in its scope by necessity, or the empirically real limitation of our existence, which acts in opposition to the Good and as a screen of sorts between creature and creator. Thus, in terms of COVID-19, necessity is the ripe material conditions through which the virus spreads. Force on the other hand, manifests itself in the arrogant demagoguery and the blind public acceptance of it by so many, a phenomenon particularly evident in the Trump-era United States. The result has been to transform so many living people into inert matter. By late February of 2021, American COVID-19 deaths surpassed 500,000, making for a monumental loss of human lives.

The Butterfly of Force

In Apollo’s Arrow, the differences between SARS-1, SARS-2, the flu, and the common cold are set out clearly and in layperson’s terms. Christakis is as comfortable with unpacking medical findings as he is referencing popular television programs and movies. In this time of rampant misinformation, a clear explanation of something as simple as “flattening the curve” or the decision to suspend schools during lockdown is one of the book’s greatest accomplishments. It offers the reader a way to conceptualize the nuances of the pandemic and perhaps would make an apt read to suggest to those family members still influenced by the misinformation of alluring but baseless online videos and social media posts.

Christakis highlights this important point: “The epidemics of emotions and of misinformation intersect in worrisome ways with the underlying epidemic of the pathogen itself” (169). The loss of truth amidst the emergence of fact-denying politicians coupled with swindlers interested in profiting from the calamities of the virus is a perfect example of that which is radically new during COVID but simultaneously as ancient as the scourge of disease. Some political leaders viewed the truth of COVID as a threat to their power and thus took refuge in lies – no matter what the death toll. The truth was purposefully covered over by those hungry for force’s power and prestige.

Beginning by chronicling the spread and development of COVD-19, Apollo’s Arrow moves into a description of epidemics across human history. In attempting to conceptualize the collective interconnection at the heart of COVID’s rapid spread across the planet, Christakis calls upon Edward Lorenz’s famous 1972 butterfly anecdote. To paraphrase, Lorenz argues that a butterfly flapping its wings in Beijing may be the cause of a tsunami in New York City or more accurately, a virus moves into a human body in Wuhan and within six months, New York City has been economically, socially, and medically brought to its knees (31). Christakis rightly notes that the horrifying and enticing aspect of this theory is that it upends our sense of order, predictability, and moral certitude in the world. It is a theory of pure necessity and accepting it is not without serious consequence to our own notions of morality: to act morally when cause and effect are uncertain is a frightening proposition. The necessary laws of cause and effect can be unpredictable, and an action of little consequence may have been maliciously enacted while a catastrophic event may spring from a gentle or even kind gesture. The screen or barrier between the earth and the Good (or God) thus becomes painfully evident: on earth, a seemingly good or neutral act may not lead to a neutral or good consequence. Earthly existence is always a mixture of good and evil and never pure goodness.

In a similar sense, Weil’s notion of force suggests the unpredictability of our actions and defies the idea that we are in complete control. “Force,” wrote Weil, “is as pitiless to the man who possesses it, or thinks he does, as it is to its victims; the second it crushes, the first it intoxicates.” By the time it has us in its grasp, force is not something humans can control. Those who wield force – e.g., leaders and lawmakers – become objects and lose the informed subjectivity that makes them thoughtful individuals. These oppressors foolishly assume that they are in control or force while in actuality, force controls them. They are slaves to power, and they do not recognize that they are in chains.

Weil recognizes the powerlessness of both oppressor and oppressed when they are caught in the binary position of force. But force is not the end of ethics because we can bring it into balance when we refuse to become wild with possessing it or attempt to bend it to our own will. In times of war or disease, force runs rampant and no human is left unscathed when she falls into its path. When necessity played out the horrific reality of COVID, those who wielded power all to regularly turned to lies and control of others by cunning action or deliberate inaction in order to preserve their power through force.

And yet, force is not completely beyond human control. Recall that necessity implements limitations on force in the very physical laws of material existence. Similarly, while no one can strong-arm force, it is possible to bring force into an ethical balance. Indeed, force maintains an ethical saving grace: it brings about the kind of suffering that is a precondition of truly understanding justice and love. To experience the affliction of oppression creates the conditions for the possibility of the miracle of love. To suffer creates the possibility within a person to choose not to inflict suffering upon another. This choice halts the cycle of lies and violence through an ethical balance that can limit force before we are taken up in its sway. With one’s own balanced reaction, fore-fronting suffering and ultimately love, force’s power is curtailed.

With Force on Their Side?

At one point every human being carries the youthful pride of thinking that force will always be on her side. It is not until we forsake force that we understand how unbalanced and unethically we have behaved. Consider the rumored “COVID parties” or simply the number of people who choose not to take the virus seriously until it has affected them personally. Despite public health warnings, there are myriad examples of people who believed that the virus was no more than the flu and that it could not harm young and healthy people. Many people who wished they had taken the lockdown protocols more seriously, realized only too late that no one can control the direction of force once they are in its grasp.

To be struck by force is to be confronted with the impossibility of certainty. After that happens, one cannot remain ethical and ignore one’s own responsibility to seek balance. This draws the distinction between the calculated oppressor and the ignorant oppressed: those who are liars or those who have been lied to. While participants of “COVID parties” may or may not be ethically culpable, it is clear that the political leaders who understood the consequences and nevertheless wielded the force behind the virus for their own power and political clout, are absolutely ethically reprehensible. These are clear examples of oppressors who have covered over truth and are ethically blameworthy.

To return to the logic of Edward Lorenz, the recognition that the butterfly may cause the tsunami should not lead to apathy or an end to ethics. Rather, an attentive mindset must seek to implement balanced safeguards against that which is beyond human control. By observing the physical necessity that limits force, one can recognize the potential construction of ethical limitations. Force admits to limits and we have an obligation to bring it into an ethical balance via our suffering and love.

Weil claims that force is “at the very center of human history” and that the Iliad as a story, is the “purest and loveliest of mirrors” in that it shows us this movement of force. COVID-19 is not so much a mirror, as a magnifying glass, amplifying that which was already present but was overlooked or purposefully ignored. Force brings to light the social, economic disparities in our sociopolitical structure. The logic of force set in motion in response to COVID-19 reveals our society’s insensitive treatment of the elderly and its cruel behaviours toward racialized groups. Furthermore, the virus brought to light an economic structure reliant on a class of people being paid less than a living wage so that a small elite group could stockpile more money than could ever be spent in a thousand lifetimes. This structure creates the necessity of illness and death for some but health and life for others. Weil echoes that observation: “moral death is always brought about by an obsession in regard to money.” If the Iliad’s mirror is pure and lovely, the mirror of COVID-19 is vile but equally pure. Reflected in the mirror darkly, this is who we are.

On the Abolition of all American Individualism

One motif that continually arises for Christakis is the difference between individual and group action: the virus divides us, creates scapegoats, and vilified others, but so too does it situate us under the arguably disingenuous banner “we’re all in this together.” The reaction of individuated separation is examined by Christakis in chapters three through five and the possibilities of collective action are taken up in the final three chapters of the book. Time and again, he draws diverse interconnections: between our physical and economic wellbeing; the individual’s health and the health of the community; the physical epidemic and the epidemic of existential despair. Mental, physical, economic, and social-political facets are all weaved tightly together.

While Christakis does a wonderful job of noting the differences between the individual and the collective, the American ideal of individual freedom and American capitalism are not given enough weight. (For a thoughtful account of this phenomenon, see Wade Davis’ article on the unraveling of America under the weight of COVID-19.) Emphasizing this distinction is important in a Weilian sense because it recognizes the necessity of the economic system that leads COVID-19 to be such a markedly vile mirror. As Weil notes in her Lectures on Philosophy: “The most important question is that of finding out what are the causes of social oppression.” One of those causes, says Weil, is the problem of lying, of “covering up oppression.” The loss of truth alienates me from my neighbor and from recognizing her social oppression. When that occurs, we are not all in this together.

Christakis falls into this American individualist trap when discussing the lack of autonomy for doctors during the time of COVID-19. On the one hand, Christakis rightly notes the deplorable muzzling of facts and the “ham-fisted edicts trying to stop [medical] personnel from speaking out” across America (152). On the other hand, the central problem does not seem to be a lack of autonomy given to medical practitioners, as Christakis suggests, but rather that an all-encompassing autonomy is thrust upon them. In the American healthcare system, medical practitioners are individuated contractors working in hospitals, replaceable by any number of other doctors or nurses. As such, these people did not lose autonomy but rather, they were denied the connections to one another and the community. Again, in her Lectures on Philosophy, Weil notes that society is necessary for the thinking individual to emerge. We are not a series of individuals who come together to form a society, but rather, we are given the opportunity to be individuals by the formation of a just society. The problem in America is not so much a loss of autonomy but rather the lack of a communal societal foundation. Weil notes that society so conceived creates “the great beast” that citizens blindly follow. If a more nuanced and thoughtful community is built, people can grow just and strong roots together.

True, Christakis, does not come down as hard as a Weilian may hope against an especially malignant brand of American individualism. But he does devote the final three chapters of his book to the importance of the community: working-class and racial disparities, solidarity, cooperative will, and mutual aid; he considers the distinction and cross-over between self-interest and the common good; and he notes the possibility of shared identity via catastrophe, touching on the social justice focused ideas that are exemplified in articles such as Arundhati Roy’s ‘The pandemic is a portal’ or Alexis Shotwell’s “The Virus is a Relation.”

Gravity and Grace

The Weilian notions of attention, of teaching, and of cooperation are key for the “saving grace” community-oriented portion of Christakis’ book. The ways in which Christakis believes we can look forward and do better are often aligned with Weil’s life and work. While recognizing the staggering losses of COVID-19, Christakis pivots in these final chapters to the productive possibilities that the virus contains. COVID-19 has demanded us to imagine otherwise, to think our world in new ways, and to confront the workings of force and the demands of necessity.

Despite having finished the book before the vaccine was unveiled, Christakis’ estimate of the post-pandemic timeline seems both disheartening and realistic. It will be years until we “return to normal” and by that time, “normal” will be an altogether different thing than it was in the fall of 2019. But “possibility” is where Christakis ends his book, which aligns with Weil’s notion of “grace.”

For Weil, grace, like force, is that which we can prepare for and in so doing perhaps bring into balance. Beyond this preparation, grace is out of our hands and all we can do is wait for its arrival. It may be beyond us, but the only way grace can manifest is through our actions, attention, and openness.

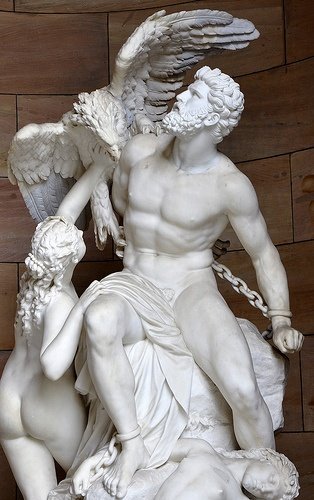

In the final paragraphs of his book, Christakis turns to the character of Prometheus, a proto-Christ figure for Weil. Prometheus gives humanity the possibly cruel, possibly kind gift of “hope.” This is the prospect of grace, lodged in our stubborn human desire to hope beyond the realm of the real. Against the backdrop of the cruel necessity of plague emerges a truly Weilian contradiction: the hope that brings about grace is as entwined with the human condition as the power-hungry deceit that utilizes force. It is up to each of us to bring these two extremes into an ethical balance.

Kathryn Lawson is a Ph.D. candidate in philosophy at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Her dissertation “Decreation for the Anthropocene,” examines Simone Weil’s philosophy in order to grapple with the contentious anthropocentric epoch and humanity’s ecological responsibilities. She is also on the editorial board of Attention.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of E. Jane Doering and Ronald Collins in the preparation of this review essay.

Sources

Simone Weil, “The Iliad or the Poem of Force” in The Simone Weil Anthology, New York, Grove Press, 2000, Sian Miles ed. (online version here)

____, Intimations of Christianity Among the Greeks, New York: Routledge, 1998, ed. and trans. by Elizabeth Chase Geissbuhler.

_____, Lectures on Philosophy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997, High Price trans.

4 Recommendations