“An Argumentative Jew”: Leon Wieseltier contra Simone Weil

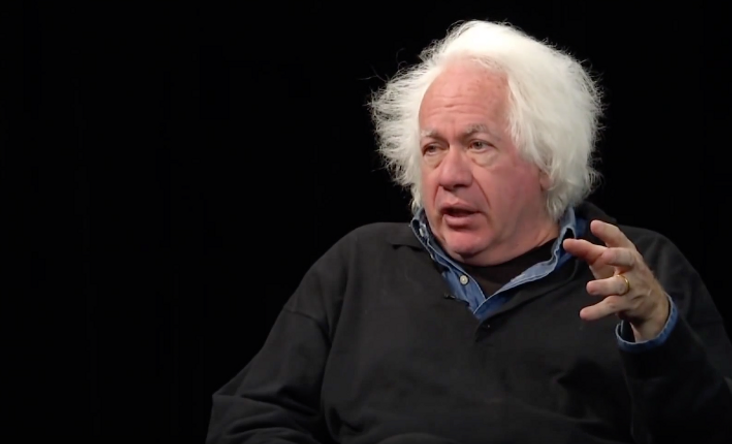

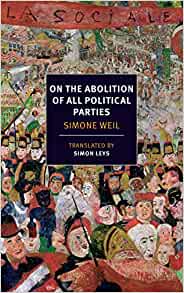

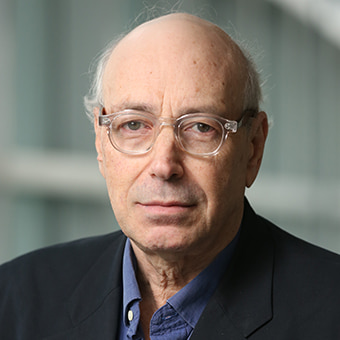

Palle YourgrauIn his essay, “The Argumentative Jew” (The Jewish Review of Books, Winter, 2015), Leon Wieseltier, formerly literary editor of The New Republic, takes Simone Weil to task for proposing, in her 1943 essay, On the Abolition of All Political Parties (2013), a model of governance that he believes contradicts both the republican ideal of democracy and the tradition of Jewish interpretation and argumentation.

On Rousseau & our republican ideal

Weil begins her essay, Wieselter writes, with “an endorsement of Rousseau and proceeds to develop her own alarmingly Rousseauist vision of perfect society-wide agreement”:

“Rousseau took as his starting point two premises. First, reason perceives and chooses what is just and innocently useful, whereas every crime is motivated by passion. Second, reason is identical in all men, whereas their passions most often differ. From this it follows that if, on a common issue, everyone thinks alone and then expresses his opinion, and if afterwards all these opinions are collected and compared, most probably they will coincide inasmuch as they are just and reasonable, whereas they will differ inasmuch as they are unjust or mistaken. It is only this type of reasoning that allows one to conclude that a universal consensus may point at the truth. Truth is one.” (emphasis added)

(pp. 5-6 )

“Weil,” according to Wieseltier, “describes these assumptions as the basis for ‘our republican ideal’.” He sees them as evidence, for Weil, that “the abolition of disagreement, when it is not coerced, is a promise of union and peace.” He introduces, by contrast, what he describes as “another republican ideal, which recognizes the inevitability, and even the nobility, of ‘faction’ and chooses compromise and respect over conformity and massified certitude. Reading Weil, one yearns for Madison.” (emphasis added).

The value of disagreement

One also yearns, Wieseltier suggests, for the Jewish tradition in which “disagreement is not only real, it is also ideal.” He quotes from a Mishnah about a quarrel between the house of Hillel and the house of Shammai, “a quarrel for the sake of heaven [which, therefore] will endure,” and comments: “The endurance of a quarrel: What sort of aspiration is this?” Apparently, it is a great aspiration. He quotes Rabbi Moses Schick: “Sometimes it is our duty to make a quarrel . . . For the sake of truth, we are not only permitted to make a quarrel, we are obligated to make a quarrel.” Such quarrel, according to Wieseltier, is a recipe for peace: “A quarrel . . . if practiced with methodological integrity . . . is evidence of coexistence.” “Emotion,” he concludes, “is private and opaque, but reason is public and lucid. . . . Judaism evolved and progressed as an alliance of the heart and the head. The heart alone would not have sufficed, certainly not for a tradition whose essential act is the act of interpretation.”

In response, let me say that I have no wish to pick a quarrel about anything Wieseltier says about the Jewish tradition. Let us take what he has to say here as the truth. But if it is true that “the essential act” of this tradition is interpretation, I confess to finding his commentary on Weil a poor representation of that tradition. For Wieseltier’s interpretation of Weil’s essay gets her reasoning exactly backward. Weil, according to Wieseltier, chooses “conformity and massified certitude” over “compromise and respect”, whereas the entire thrust of Weil’s essay is an argument against “conformity and massified certitude”.

Nor, contra Wieseltier, is Weil in opposition to what he describes as the Jewish tradition of quarrel and disputation. All this is clear from every page of Weil’s essay, including the very passage he quotes. He simply misreads it. In that passage, in support of Rousseau, Weil proposes a conditional: “if everyone thinks alone” on a common issue and expresses their opinion . . . . This condition, which speaks of “thinking alone”, represents the very opposite of the idea of “conformity and massified certitude.” (emphasis added)

Collecting together individual thoughts is entirely different from engaging in collective, “massified”, conformist thinking. Given this condition, Weil says, “inasmuch as they are just and reasonable”, people’s opinions will coincide. Moreover, she insists, “it is only this type of reasoning that allows one to conclude that a universal consensus may point at the truth.”

Truth alone is an end

This ideal condition, however, is rarely, if ever, satisfied. Passions, Weil insists, cloud and distort one’s reason – especially given the influence of political parties, designed to inflame one’s passions. Thus, to reach the truth, it is not sufficient to take a poll or canvass voters. (Therein, for Weil, lies the Achilles heel of democracy, about which, more later.) It is thus necessary to employ other means to get to the truth, in particular, disputation and argument. But, Weil insists, disputation and argument are not an end in themselves; they are merely a means, wherein lies their only justification. (And the same, for Weil, we’ll see, holds true for democracy.) Contra Wieseltier, these means (disputation and argument) are not “ideal”, and are not an end in themselves. Truth alone (in the end, only goodness) is an end. Indeed, Wieseltier himself should have acknowledged this, since, as we’ve seen, he quotes Rabbi Moses Schick as saying, “Sometimes it is our duty to make a quarrel . . . . For the sake of truth we are not only permitted to make a quarrel, we are obligated to make a quarrel.” (emphasis added). Weil (herself, a fearless and frequent disputant) would agree.

To consider disputation itself an ideal, an end, risks the loss of the true end, namely, the truth. “There are broad-minded people,” writes Weil, “willing to acknowledge the value of opinions with which they disagree. They have completely lost the concept of true and false.” (p. 32).

That is, they have only the concept of agreement and disagreement, and liberally, as the saying goes, “agree to disagree”. While others, says Weil, “having taken a position in favour of a certain opinion, refuse to examine any dissenting view. This is a transposition of the totalitarian spirit.” (Ibid.) Yet Wieseltier, in describing Weil as recommending “conformity and massified certitude”, chooses to identify Weil herself as one of these others, these totalitarians, who refuse to examine any dissenting view. “Goodness alone,” says Weil, “is an end. Whatever belongs to the domain of facts . . . — money, power, the state, national pride, economic production, universities, etc. –- pertains to the category of means. Collective thinking, however, cannot rise above the factual realm. It is an animal form of thinking . . . with [a] dim perception of goodness.” (p. 12) Are those the words of someone who recommends “conformity and massified certitude”?

And here we arrive at the central thesis of Weil’s essay and the central failure of Wieseltier to understand Weil’s argument against the institution of political parties. Political parties, Weil argues, stoke collective passions, inducing a form of disagreement or disputation that has no intrinsic relation to the truth, but only to political, factional power. She advances three theses:

The real danger to truth: collective passions

1. “A political party is a machine to generate collective passions.

2. “A political party is an organization designed to exert collective pressure upon the minds of all its individual members.

3. “The first objective and also the ultimate goal of any political party is its own growth, without limit.” (p. 11)

As a consequence, Weil asserts, “every party is totalitarian – potentially, and by aspiration.” (Ibid.) Individual thought – the only genuine kind of thought, according to Weil, that exists – is replaced by factional loyalty, loyalty to a party. (Is the contemporary political situation in the United States not a striking example of this?) Indeed, this is true, she believes, of all “parties”, not just political: “When Einstein visited France, all the people who more or less belonged to the intellectual circles, including other scientists, divided themselves into two camps: for Einstein or against him.” (p. 33) (For details about that visit, see Jimena Canales, The Physicist and the Philosopher: Einstein, Bergson, and the Debate that Changed Our Understanding of Time (2015).) And something similar arose, she comments, with disputations around Cubism vs. Surrealism, people who were Giden vs. Maurrassian, and so on. “To achieve celebrity,” Weil adds, mordantly, “it is useful to be surrounded by a gang of admirers, all possessed by a partisan spirit.” (Ibid.)

The Founders’ skepticism

Yet “reading Weil,” says Wieseltier, “one yearns for Madison.” Has he forgotten the skepticism, even hostility, with which the founding fathers regarded the idea of political parties? Perhaps he should yearn a bit more for Jefferson, who famously wrote:

“. . . I never submitted the whole system of my opinions to the creed of any party of men whatever, in religion, in philosophy, in politics, or in anything else where I was capable of thinking for myself. Such an addiction is the last degradation of a free and moral agent. If I could not go to heaven but with a party, I would not go there at all.”

(Letter to Francis Hopkinson, March 13, 1789)

Disputation, then, for Weil, is a means, not an end, a means all too easily deflected from its proper end, the truth, by the influence of political parties, which results in collective thinking (or more precisely, collective non-thinking) on behalf of one’s chosen side or party. More dramatically, Weil argues that the same is true of democracy itself. For Weil, it, too, is only a means. The true end of democracy is not democracy itself (i.e., collective thinking or collective voting) but rather truth and justice. “The true spirit of 1789,” writes Weil, “consists in thinking, not that a thing is just because such is the people’s will, but that, in certain conditions, the will of the people is more likely than any other will to conform to justice.” (7) (Which corrects Wieseltier’s misunderstanding of Weil’s approval of Rousseau.) “Democracy,” Weil adds, and “majority rule, are not good in themselves. They are merely a means toward goodness. For instance, if instead of Hitler, it had been the Weimar Republic that decided, through a most rigorous democratic and legal process, to put the Jews in concentration camps and cruelly torture them to death, such measures would not have been one atom more legitimate than the present Nazi policies.” (p. 5)

Yet Weil goes even further. Not only is democracy, as such, a means (towards justice or goodness), not an end, but in truth, “we have never known anything that resembles, however faintly, democracy. . . . Any issue that does not pertain to particular interests is abandoned to collective passions, which are systematically and officially inflamed” (p. 10) – inflamed, in particular, by the influence of political parties, with the result that individual thought (i.e., genuine thought) is replaced by collective non-thought, what Wieseltier calls “conformity and massified certitude”, which he accuses Weil of recommending.

Conflating means with ends

As an interpretation of Weil’s essay, then, Wieseltier’s critique is a failure. At the same time, he comes close to conflating means with ends, insofar as he praises a tradition that he says (incorrectly, I have argued) takes disagreement, disputation (as opposed to truth) as an “ideal”, and speaks of “the nobility of ‘faction’.” This is not to say that Weil’s substantive thesis, recommending the abolition of all political parties, is beyond criticism, beyond disagreement or disputation. Weil, herself, however, I have been suggesting, in spite of what Wieseltier has written, is the last person who would deny the importance, indeed, the necessity, of seeing whether her ideas can stand up to strict scrutiny, to the rigors of disputation.

Palle Yourgrau is the Harry A. Wolfson Professor of Philosophy at Brandeis University. His many works include Simone Weil (Reaktion Books: “Critical Lives,” 2011) and Death and Nonexistence (Oxford University Press, 2019).

5 Recommendations