Inside Issue 11: New and Forthcoming

Ronald KL Collins

What’s New in this Issue

In this issue we are fortunate to have a wealth of original contributions starting with D.K. Levy’s and Marina Barabas’ newly translated summary of the notes Simone Weil made concerning a lengthy essay she sent to Father Joseph-Marie Perrin. As Levy and Barabas point out, the notes might serve as an aid to readers of Weil’s essay “Concerning the Pythagorean Doctrine.” This is the first time these summary notes have been translated into English replete with an invaluable introduction by Levy.

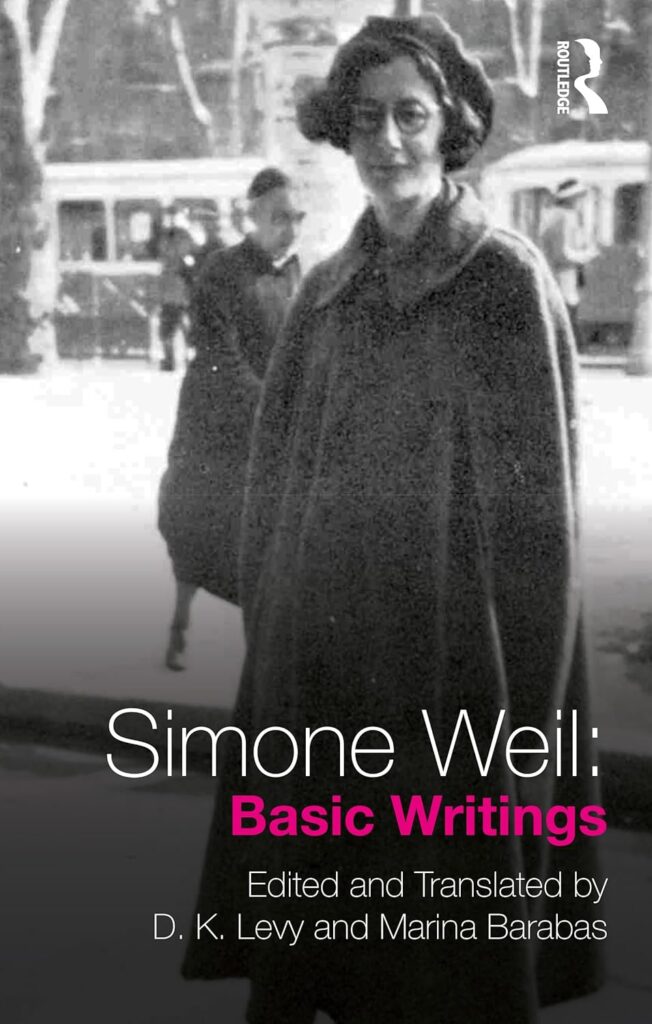

Levy and Barabas have also just released a major new literal translation, replete with illuminating notes and introductory essays, of important selections from Weil’s works. Their book is titled Simone Weil: Basic Writings (Routledge: London, 2024). Eric Springsted reviews that book followed by a reply by Levy and a rejoinder by Springsted. Note: sometime this summer Attention will host an online exchange on the Levy-Barabas collection and translation of Weil’s works. Thereafter, in the next issue of Attention, we will have a Q&A discussion about their book — stay tuned.

Michela Dianetti (our Italty correspondent) has a thoughtful and wide-ranging interview with Maura Del Serra, former Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Florence, who recently did a major Italian translation of Weil’s L’ enracinement. That interview, conducted in Italian, has been translated for this issue.

Our own Jane Doering has an inviting and instructive summary of the 2023 French Colloquy on “Decreation, Capitalism, Ecofeminism, and Sacrifice in the Cadre of Work.”

Finally, we round out the original contributions with yet another commentary on Gustave Thibon’s Gravity and Grace.

Newly Translated Work by Weil

- “Rationalisation: by Simone Weil,” Global Labour Journal, vol 15, no.1 (2024) (translated by William Tilleczec: “The text translated here as ‘Rationalisation’ is, to my knowledge, the first English version of a presentation given by Simone Weil in February 1937 and included in her complete works under the French title “Rationalisation.”)

“The word ‘rationalisation’ is rather vague. It designates methods of industrial organisation – ones that are more or less rational – which currently reign in the factories in various forms. which currently reign in the factories in various forms. Indeed, there are several methods of rational rationalisation, and each boss applies them in his own manner. But they all have some points in common, and all make claims to science, in the sense that methods of rationalisation are presented as scientific methods for the organisation of labour [travail travailvail].

rationalisation are presented as scientific methods for the organisation of labour[travail].

At first, science was nothing other than the study of the laws of nature. It intervened later in production via the invention and the fine-tuning of machines, and via the discovery of procedures that made it possible to make use of natural forces. Finally, in our era, towards the end of the previous century, one began thinking of applying science not only to the use of natural forces, but to the human force of labour. This is something completely new, whose effects we are beginning to perceive.

The term“industrial revolution ”is often used to designate precisely the transformation that took place in industry once science was applied to production and large-scale industry made its appearance. But one could say that there has been a second industrial revolution. The first was defined by the scientific use of inert matter and of natural forces. The second was defined by the scientific use of living matter, that is, of human beings [des hommes].

Rationalisation appears as a perfection of production.If one considers rationalisation from the point of view of production alone, it can be filed amongst the successive innovations of which industrial progress is made; whereas, if we take up the perspective of the worker, the study of rationalisation is part of a very great problem, the problem of an acceptable regime in industrial enterprises. Of course, I mean: acceptable for the workers; and it is above all from this angle that we ought to envisage rationalization. For if the spirit of trade unionism [syndicalisme] differs from the spirit which animates the best leaders of our society, it is above all because the union [syndical]movement is more interested in the producer than in the product–contrary to bourgeois society, which is above all interested in production, not in the producer.

The question of the most desirable regime within industrial enterprises is one of the most important –perhaps even the most important –for the workers’ movement. It is thus all the more surprising that the question has never been posed. To my knowledge, it has not been studied by the theorists of the socialist movement; neither Marx nor his disciples dedicated any works to it, and in Proudhon, one finds only hints of it. The theorists were perhaps not well placed to deal with this subject, lacking the experience of being themselves a cog in the factory. . . .

[The remainder of the translated work is set out here.]

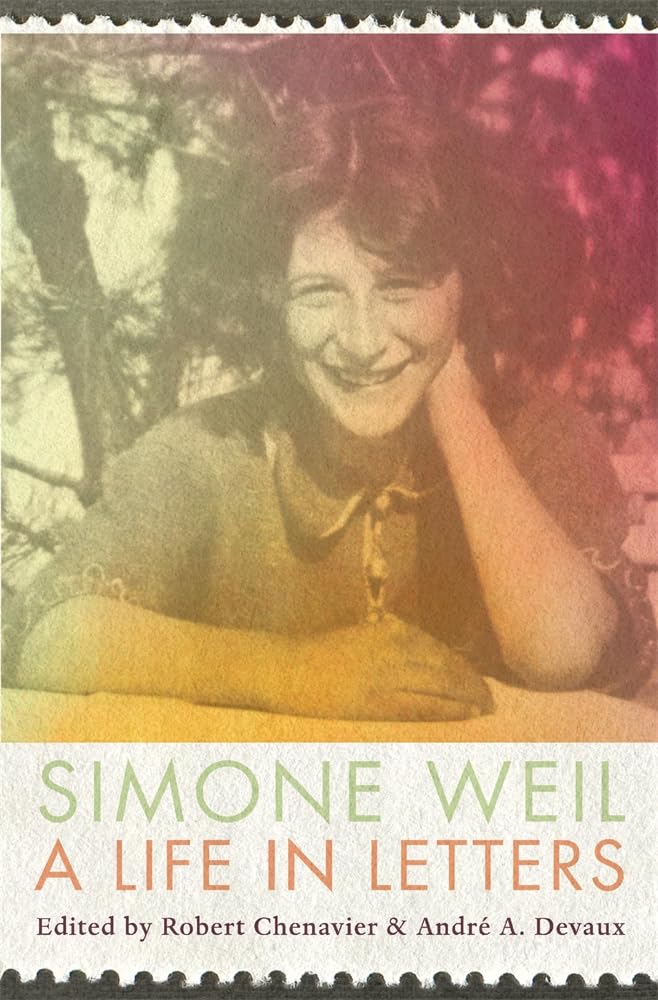

Forthcoming Book

- Simone Weil: A Life in Letters (Belknap Press / Harvard University Press (Aug. 27, 2024), Robert Chenavier & André A. Devaux, editors, with Nicholas Elliott translator, and Marie-Noël Chenavier-Jullien, Annette Devaux, and Olivier Rey, contributors

“The inspiring letters of philosopher, mystic, and freedom fighter Simone Weil to her family, presented for the first time in English.

Now in the pantheon of great thinkers, Simone Weil (1909–1943) lived largely in the shadows, searching for her spiritual home while bearing witness to the violence that devastated Europe twice in her brief lifetime. The letters she wrote to her parents and brother from childhood onward chart her intellectual range as well as her itinerancy and ever-shifting preoccupations, revealing the singular personality at the heart of her brilliant essays.

The first complete collection of Weil’s missives to her family, A Life in Letters offers new insight into her personal relationships and experiences. The letters abound with vivid illustrations of a life marked by wisdom as much as seeking. The daughter of a bourgeois Parisian Jewish family, Weil was a troublemaking idealist who preferred the company of miners and Russian exiles to that of her peers. An extraordinary scholar of history and politics, she ultimately found a home in Christian mysticism. Weil paired teaching with poetry and even dabbled in mathematics, as evidenced by her correspondence with her brother, André, who won the Kyoto Prize in 1994 for the famed Weil Conjectures.

A Life in Letters depicts Simone Weil’s thought taking shape amid political turmoil, as she describes her participation in the Spanish struggle against fascism and in the transatlantic resistance to the Nazis. An introduction and notes by Robert Chenavier contextualize the letters historically and intellectually, relating Weil’s letters to her general body of writing. This book is an ideal entryway into Weil’s philosophical insights, one for both neophytes and acolytes to treasure.”

Three New Books

- A. Rebecca Rozelle-Stone, Simone Weil: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, May 2024)

This Very Short Introduction provides an overview of the intriguing and provocative life and ideas of twentieth-century French philosopher, mystic, and social activist Simone Weil. Weil was not a typical, systematic philosopher. Despite her short life, Weil’s philosophy has much to offer us in our times of personal, communal, political, and environmental crises, both in the breath and poignancy of her philosophy, and the topics it covers.

In keeping with Weil’s spirit to consider and address laypeople, Rozelle-Stone takes readers, including those who have had little or no previous exposure to Weil or philosophy, on an accessible journey of Weil’s major philosophical impacts. This exploration consists of seven chapters highlighting: her life and manner of death, both characterized by attention; the influence of ancient Greek ideas on her philosophy; her thoughts on labour and politics; her unique and ecumenical religious inspirations, stemming from Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism; her ethical philosophy centred on a specific notion of attentiveness; her understanding of beauty as connected to fragility but also eternity; and finally, her legacy and influence on contemporary writers and issues, particularly as she may help us navigate and critically assess the growing convergence between religious fervour, late capitalist and corporate values, and authoritarian politics.

- Kathryn Lawson, Ecological Ethics and the Philosophy of Simone Weil (Routledge, May 13, 2024)

This book places the philosophy of Simone Weil into conversation with contemporary environmental concerns in the Anthropocene.

The book offers a systematic interpretation of Simone Weil, making her ethical philosophy more accessible to non-Weil scholars. Weil’s work has been influential in many fields, including politically and theologically-based critiques of social inequalities and suffering, but rarely linked to ecology. Kathryn Lawson argues that Weil’s work can be understood as offering a coherent approach with potentially widespread appeal applicable to our ethical relations to much more than just other human beings. She suggests that the process of “decreation” in Weil is an expansion of the self which might also come to include the surrounding earth and a vast assemblage of others. This allows readers to consider what it means to be human in this time and place, and to contemplate our ethical responsibilities both to other humans and also to the more-than-human world. Ultimately, the book uses Weil’s thought to decanter the human being by cultivating human actions towards an ecological ethics.

This book will be useful for Simone Weil scholars and academics, as well as students and researchers interested in environmental ethics in departments of comparative literature, theory and criticism, philosophy, and environmental studies.

Related

- Kathryn Lawson & Joshua Livingstone, eds., Hannah Arendt and Simone Weil: Unprecedented Conversations (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024)

- Cynthia R. Wallace, The Literary Afterlives of Simone Weil (Columbia University Press, April 23, 2024))

“The French philosopher-mystic-activist Simone Weil (1909–1943) has drawn both passionate admiration and scornful dismissal since her early death and the posthumous publication of her writings. She has also provoked an extraordinary range of literary writing focused on not only her ideas but also her person: novels, nonfiction, and especially poetry. Given the challenges of Weil’s ethic of self-emptying attention, what accounts for her appeal, especially among women writers?

This book tells the story of some of Weil’s most dedicated―and at points surprising―literary conversation partners, exploring why writers with varied political and religious commitments have found her thought and life so resonant. Cynthia R. Wallace considers authors who have devoted decades of attention to Weil, such as Adrienne Rich, Annie Dillard, and Mary Gordon, and who have written poetic sequences or book-length verse biographies of Weil, including Maggie Helwig, Stephanie Strickland, Kate Daniels, Sarah Klassen, Anne Carson, and Lorri Neilsen Glenn. She illuminates how writing to, of, and in the tradition of Weil has helped these writers grapple with the linked harms and possibilities of religious belief, self-giving attention, and the kind of moral seriousness required by the ethical and political crises of late modernity. The first book to trace Weil’s influence on Anglophone literature, The Literary Afterlives of Simone Weil provides new ways to understand Weil’s legacy and why her provocative wisdom continues to challenge and inspire writers and readers.”

Previously Unnoticed MA Thesis

- Yvana Mols, Weil, “Truth and Life: Simone Weil’s pedagogy as auto-philosophical therapy of soul,” Masters Thesis, Institute for Christian Studies, Toronto /Ontario (2007)

New Scholarly Articles

- Alessandra Aloisi, “Art and the Power of Distraction: Bergson, Benjamin, and Simone Weil” in The Politics of Curiosity (2024)

- Sandra Lehmann, “Bracketing the Future, or Simone Weil’s Mystical Politics,” Journal for Religion and Transformation in Contemporary Society, vol. 3 (Feb.2, 2024)

- Voigt Hogg, “On the orientation of the soul toward grace or God: Simone Weil and Robert Bresson,” University of Otago (2024)

YouTube: Newly Posted Items

- “Simone Weil on Cooperation,” Columbia Center for Contemporary Critical Thought, YouTube (Nov. 30, 2023)

Bernard E. Harcourt, Frieda Ekotto, and Benjamin P. Davis discuss Simone Weil and Cooperation for Coöperism 7/13 @ColumbiaLawSchool1. Read more here: Wednesday, November 29, 2023, at Columbia University.

YouTube: Previously Unnoticed Post

- Stephen Plant, “The SPCK Introduction to Simone Weil,” SPCK (2007)

Overview

Simone Weil was one of the most original philosophers and political thinkers of the twentieth century. During her life, her writings were almost unknown beyond a few close friends. Only after her death at age 34 did her work reach a wider audience, including Pope John XXIII, Pope Paul VI, Simone de Beauvoir, Leon Trotsky, and Iris Murdoch.

Weil was born in 1909 to nonpracticing Jewish parents and was an agnostic until her late twenties, when she became a Christian. She had a refreshing creativity and a rare ability to confront theological complacencies. She wrote about the nature of God, the nature of work, suffering, the importance of improving conditions for factory workers, and our duty to our community. She addressed key philosophical, theological, and ethical issues, many of which are as important today as they were in her own time. Here, Stephen Plant makes Weil’s often complex and challenging thought accessible to a wide audience. He outlines a few of the central themes of Weil’s thought and provides short extracts from her writings. This revised and expanded edition is an ideal introduction to Weil for both students and the general reader.

1 Recommendation