An Interview with Lenora Champagne

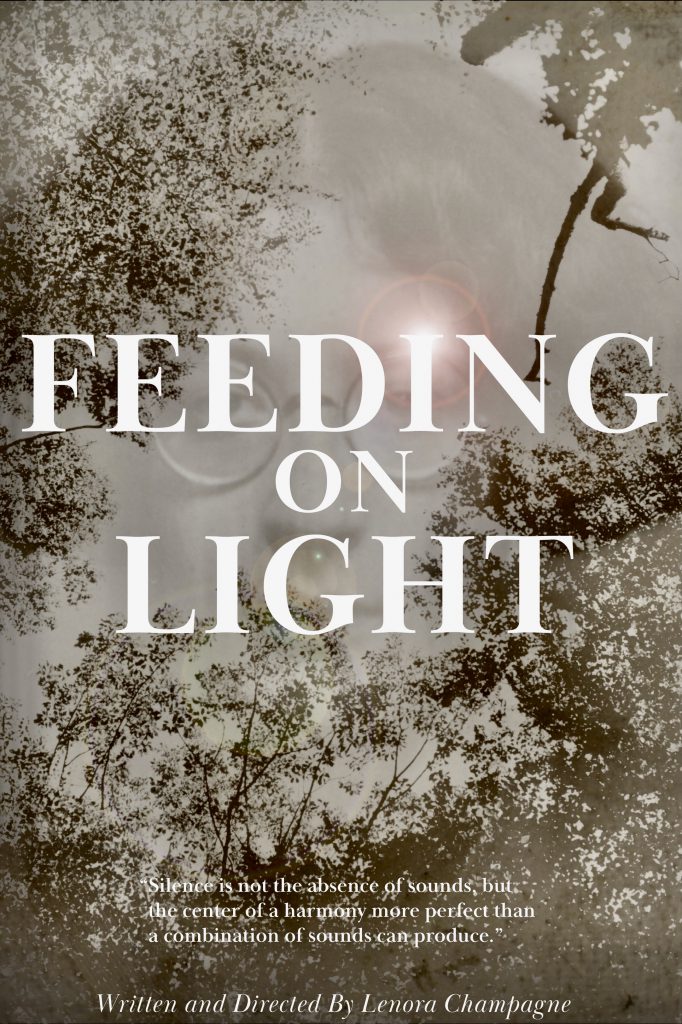

RONALD KL COLLINS“Feeding on Light”

Lenora Champagne is an American playwright, performing artist, and director. Champagne is Professor of Theatre and Performance at Purchase College. She received her Ph.D. in performance studies from New York University, and teaches a class in Solo Performance in Spring for NYU’s Gallatin School.

Professor Champagne has received numerous fellowships, awards, and commissions from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, the Jerome Foundation, and others, and has been awarded residencies at Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony, the Bogliasco Foundation, and Maison Dora Maar. She lived in Japan in 2012-13 on a Fulbright award.

She is the author of New World Plays (2015) and French Theatre Experiment Since 1968 (1984), editor of Out from Under: Texts by Women Performance Artists (1993), and has contributed to Plays and Playwrights (2009), the Performing Arts Journal, and to The Iowa Review, among other publications. Her essay on theatrical adaptations of The Scarlet Letter appeared in Sharon Freidman’s Feminist Theatrical Revisions of Classic Works (2008), and in 1977 she authored an essay published in Sub-Stance: “The Beach Beneath The Paving Stones: May 1968 and French Theater.”

More recently, she offered video commentary on Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958), who captured the first-ever image of DNA.

Professor Champagne’s latest project is a play titled “Feeding on Light,” which is a collaboration that explores the life and influence of Simone Weil. The play was awarded a commission by the Inaugural Katherine Owens Fund for New Work.

“Feeding on Light” streamed from April 28th through May 2nd in Dallas at the Undermain Theatre. Ronald Collins prepared the questions, all of which were submitted to Professor Champagne by e-mail. His questions and her responses are set out below.

Light . . . exerts no pressure, has no weight; but by its means the plants and trees reach towards the sky in spite of gravity.

— Simone Weil, “Fragments, London” (1943)

Grace represents our chlorophyll.

— Simone Weil, Notebooks (II, 368)

The Interview

Collins: Lenora, thank you for agreeing to be interviewed and congratulations on your latest work, “Feeding on Light.” Before we go further, tell us a little bit about your familiarity with the life and thought of Simone Weil and what about both attracted your attention.

Champagne: Recently I have been going through my own journals and notebooks, and was startled to discover that I was reading Simone Weil back in the seventies and that one of my first ideas for a play, in 1979 or 1980, about the relationship between passion and suffering, was going to include Simone Weil and Flannery O’Connor! I found quotations from Weil here and there, in various notes I’d jotted down.

Back then, I didn’t know much about her life, but when Katherine Owens asked if I’d be interested in writing a play about Weil, I said yes immediately and pointed out that I had four books by or about her on my shelves. In terms of what interested me back then—I think it was the purity of the suffering, the essentialness of it. That interests me less now that I’m older and don’t romanticize suffering.

Collins: Your play is billed as a “collaboration.” Tell us about that and Katherine Owens (1957-2019) and her work. Who was she and how does she figure into the biography of “Feeding on Light”?

Champagne: Katherine asked me to write the play, which she was going to direct. We had collaborated previously—she directed my play Coaticook in Dallas and in New York City. I initially saw her work in the 90’s, when she directed a play by Erik Ehn at the Undermain that was a fabulous adaptation of Faulkner. She both directed it and performed in it, which I very much appreciate as someone who has also directed work in which I’ve performed.

Katherine was that very rare director who took risks on new work and directed the play you wrote rather than developing it forever. She worked with exciting writers and staged powerful productions in Dallas and elsewhere. She took a production about the siege of Sarajevo to Macedonia—they couldn’t get into Sarajevo at the time because it was during the siege.

We started meeting about “Feeding on Light” in upstate New York during a long weekend and exchanged notes and ideas and just hung out. I got a residency at Dora Maar in the South of France to work on the play; we were both excited about it. A couple of months later, a friend called and told me that she’d seen something that suggested Katherine had died. To say I was shocked is an understatement. We’d been in touch sporadically via e-mail and phone, but I’d had no idea she was so ill. Apparently, it was very intense and relatively quick. She was still young, just 61.

Collins: Ms. Owens once said: “I think there are two traditions in the theatre – the hermetic and the heroic.” Which approach did you employ in your latest play?

Champagne: That was Katherine speaking, not me. I think she was attracted to those kinds of plays—the hermetic and the heroic, and could handle them both beautifully. I think Simone is more of a heroic figure, but I don’t look for heroes, myself. I tend to point out their shortcomings. I tend to agree with Tina Turner that we don’t need another hero. Some of my more poetic or language-based work may be considered hermetic, but I think of it more as meditative or reflective. Writers I admire range from Virginia Woolf and Chekhov to Joy Williams and Maria Irene Fornes, with Lydia Davis and Lucia Berlin and Sarah Ruhl in there also. Something that is true of a lot of my plays and performance texts is that there is something domestic or everyday about them, with eruptions of the fantastic or lyrical. I attribute that to my Louisiana roots.

Collins: Bruce DuBose is directing “Feeding on Light.” How is it that you turned to him?

Champagne: Bruce, who is now Artistic Director of the Undermain, was co-Artistic Director with Katherine, and Katherine’s artistic and personal partner. When he expressed a desire to direct the play, I readily agreed, as probably no one knew her better. I was thrilled that he wanted to continue the work on the play that Katherine and I had begun.

Collins: As suggested by the epigraph quotes above, I am intrigued by your selection of the word light in the title of your play. As you know, it is a word (along with chlorophyll) that is of great significance in Weil’s philosophy and spirituality (e.g. Notebooks, vol. I, p. 223, Perrin & Thibon, Simone Weil as We Knew Her, p. 94). Can you, as it were, shed some light on your selection of that word?

Champagne: The title comes from a line of Simone’s in Gravity and Grace. It captured two things for me: the importance of illumination and light(ness) (grace versus gravity) for her, and that she didn’t eat. If you feed on light, you may become holy, but your body will not survive. She stopped eating, and died, but left her remarkable ideas and life story.

Collins: I gather that suffering and compassion are central themes in your play. How and why so? And on that score, what is the link to Katherine Owens?

Champagne: Katherine prioritized taking care of her father for the final two years of his life, which is when she read a lot of Simone Weil. I believe she showed compassion for him. I also think we have both had difficulty with witnessing other people’s suffering. Weil and Katherine both made themselves do it.

Collins: How do you understand Weil’s notion of “attention,” and how does it fit into the arc of your play?

Champagne: Attention is an urgent responsibility for Weil, and is emphasized in some writing that Katherine did, copying Simone’s words in French and superimposing a drawing she did of Simone. Attention is what we owe the suffering, and what we owe God. We have to recognize the humanity in another despite or even because of wanting to avoid being confronted by suffering.

Collins: Weil’s 1940-41 essay “The Iliad or Poem of Force” finds expression in your play. Why?

Champagne: Katherine was particularly interested in that essay of Weil’s. I think it’s partly because she directed The Iliad, a solo play based on the epic. I find it particularly timely, given the reliance on force and bullying that we’ve just undergone as a nation.

Collins: On a related front, Weil’s notion of force likewise finds echoes in her nearly completed play “Venice Saved.” Are you familiar with that play? If so, what is your sense of it?

Champagne: I tried to find Venice Saved, but couldn’t get my hands on it. I read your review of the play. I’d love to read it, but don’t know it.

Collins: There are three main characters (all women) in “Feeding on Light.” Who are they and what can you tell us about each by way of character snapshots?

Champagne: Simone Weil is a character in the play. She is an intellectual, awkward, a chain smoker, physically clumsy, but can be luminous. Katherine is a character in the play. She is a director, a grounded visionary, with a clear and beautiful voice. Nora is writing the play. She is skeptical, a joker, but respects Katherine and Simone. In fact, one of the challenges of the play is that I feel that I must honor both Katherine and Simone. It’s not hard to do that, but it might be more fun if I were less reverent.

Collins: Beyond the script and the characters, there is also the visual setting for your play. What can you tell us about that and how it relates to your idea of the play?

Champagne: In reading Weil’s biography, several interiors came to mind. My favorite is the hut she lived in while staying at Gustave Thibon’s farm—she found the farmhouse too comfortable, so she set herself up in an abandoned stone dwelling on the property. I might have set the entire play there, but Katherine had mentioned a black and white floor and a chandelier overhead—it referenced a church Simone had attended on the upper west side of Manhattan in 1942. Then, in Paris I went to an exhibition by the American sculptor, Kiki Smith, where I saw a piece she’d made in honor of the women who’d been burned at the stake as witches during the middle ages, and I immediately wanted a pile of stones (the Smith piece is of a naked woman with outstretched arms kneeling at the top of a pyre of wood. The sculpture is called, “Father, why have you forsaken me”). When I mentioned this to her husband, Bruce DuBose, he told me that Kiki Smith was one of Katherine’s favorite artists, so of course I wanted to honor that.

In my play Katherine and Nora are in a farmhouse together, so there has to be something normally domestic, and of course Simone’s room is cluttered with books and papers while she incessantly writes. So, the visual imagery shifts and changes—it must all be very simple. There are also projections of flames from time to time, to signify the multiple injuries Simone experienced in her various adventures.

Collins: A half-century or so ago Megan Terry (an American playwright, screenwriter, and theatre artist) wrote a play entitled “Approaching Simone” which won the 1969/1970 Obie Award for Best Off-Broadway Play. Are you familiar with that play and how, if all, does it resonate with your play on Weil?

Champagne: Yes, I’m familiar with the play—I read it back in the day and again when I started on this project. I think it feels very much like a play of its time, with a lot of use of transformations in the style of, well, Megan Terry and the Open Theatre. It’s theatrical, which is terrific, and fairly schematic. I suppose mine is more discursive.

Collins: There is some talk about a workshop accompanying the release of the play. Is that so?

Champagne: I’m directing a workshop production through Purchase College that will be streamed March 26 to 28 and Bruce is directing a staged reading at the Undermain which will be streamed April 28th through May 1st. There will be a workshop production at the Undermain in Dallas next year, hopefully post-Covid.

Collins: Finally this: In commenting on Albert Camus as a playwright, John Cruickshank wrote that Camus “used the theatre primarily as a medium for the expression and dramatization of serious ideas – philosophical problems and moral dilemmas . . . .” {Caligula and Other Plays, Penguin Books, 1984, p. 309)} As a playwright, what does the medium of theatre mean to you?

Champagne: While I am trying to express and hopefully dramatize Simone’s serious ideas in this play, I’m more typically drawn to plays that explore consciousness and language. There is reflection and even meditation on or attention to everyday things in my work. The domestic shows up, friendship is explored, nature always makes an appearance. For some time I explored women and power as a theme. Actually, as my website says:

“I’m interested in perception — in how the world looks depending on where you stand to see, and on what you’re looking for. I’m interested in representation — how the aesthetic portrayal of individuals and groups gives a picture of their ‘value in society. I’m interested in language (words, images, movement) as a means to play with and affect perception and representation. With my intricate stories and metaphors, I aim to move audiences both intellectually and emotionally – to challenge them to think and feel about the complex ways in which we are implicated in each other’s stories, and in the larger society.”

51 Recommendations