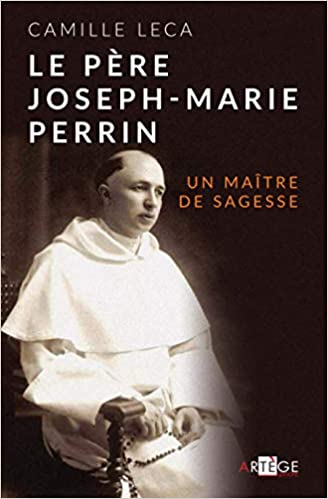

Joseph-Marie Perrin: A Biographical Sketch

French Wikipedia entry (translated & expanded)Michel Perrin (July 30, 1905 – April 13, 2002) was a French Dominican priest and resistance fighter. In 1999 the Yad Vashem committee awarded him the medal of “Righteous among the nations.” (The title is awarded by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save Jews from extermination by the Nazis for altruistic reasons.) He is also known to have been the spiritual mentor of Simone Weil.

He was born in Troyes and was the second son of Edmond Perrin, a career soldier, and Germaine de la Boullaye. He was raised in a devoutly Catholic family. In 1916, he learned that he had retinitis pigmentosa and would go blind. His older brother and one of his sisters suffered from the same disease. His mother encouraged her children to learn Braille when she heard of the Valentin Haüy Association for the blind. Perrin was encouraged by Pierre Villey, a professor and the secretary-general of the Association, to continue his studies.

Perrin already had a desire to become a priest. While on a retreat for his solemn communion, he mentioned this calling to the chaplain of his college. The chaplin replied that he should not think about it again since “blindness is an impassable obstacle to priestly ordination.”

Sometime later, his mother wrote to the future Cardinal Jean Verdier, who gave a less discouraging reply. Thanks to his mother, Michel came into contact with Father Bernadot and decided to become a Dominican. He entered the novitiate of Saint-Maximin in October 1922 and took the name Joseph-Marie Perrin.

He made his solemn profession on September 2, 1927, continued his studies, and prepared to receive ordination. Since canon law at the time did not accept the ordination of a blind man, he had to obtain a dispensation from Pope Pius XI. He was ordained a priest on Holy Saturday, 1929.

Assigned to the convent of Marseille in 1930, Perrin was in charge of assisting students. Very active as a confessor, he also devoted much time to preaching and became superior of his convent. Convinced of the importance of the role of the laity in the Church, on August 4, 1937, he founded, with Juliette Molland, the missionary Union of the little sisters of St. Catherine of Siena, which later became the Union Caritas Christi.

Caritas Christi was established as a secular institute of diocesan law on December 6, 1950. It became a secular institute of pontifical law on March 19, 1955. Father Perrin founded the Association of Priests of Caritas Christi (1961) and the Fraternities Caritas Christi (March 30, 1989).

As early as 1937, following the guidelines of the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, the Dominicans of Marseille applied themselves to fight Nazism and anti-Semitism. They regularly organized meetings devoted to a dialogue between Jews and Christians.

With the war coming, Father Perrin worked on the clandestine dissemination of the Cahiers du Témoignage chrétien. With the fathers Ambroise Stève, Réginald de Parseval, and Damien Boulogne, he organized the flight of Jews threatened by the Nazis. Appointed superior of the convent of Montpellier in 1942, Perrin was arrested by the Gestapo on August 13, 1943. After being temporarily released, he took refuge in Marseille, then in Aix-en-Provence.

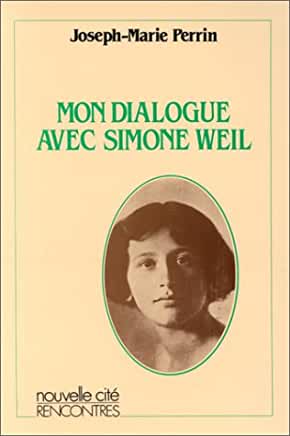

In 1940, Hélène Honnorat, a teacher and devote Catholic, informed Father Perrin that Simone Weil was in Marseille and that she wanted to do agricultural work. The two met on June 7, 1941. Sometime therefater, Perrin put Weil in contact with Gustave Thibon, who hired her as an agricultural worker. Perrin also introduced Weil to Father Louis-Joseph Lebret(founder of the journal Économie et humanisme) and to Father Jacques Loew. Weil took part in the clandestine dissemination of the Cahiers du Témoignage chrétien.

“Father Perrin laments that ‘in Simone Weil the conflict between the certitude of religious experience and her philosophical mentality went very deep,’ and that she had difficulty on account of a certain rationalism which the great discovery of Christ had not removed.”

Mario von der Ruhr, Simone Weil, London: Continuum (2006), p. 129.

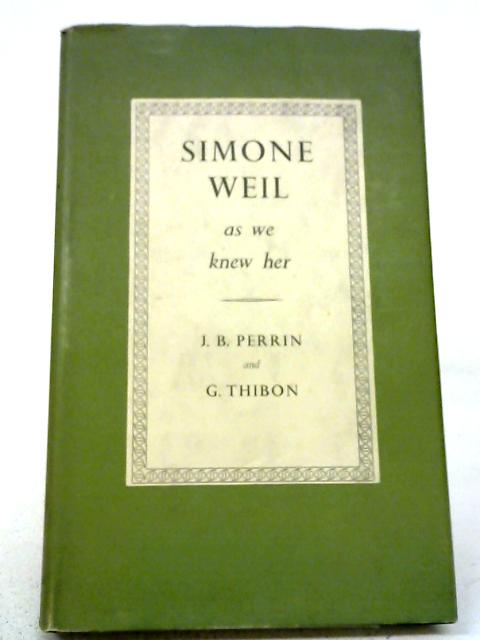

Perrin and Weil intended to write a book together on the “mystics of all religions,” but the project never materialized. On leaving Marseille, Weil bequeathed her essays of religious reflections to Perrin. From Casablanca, where she stayed for some time in a refugee camp before leaving for the United States, she again sent Perrin several long letters which along with some of her other writings Perrin published under the titles (as translated) Waiting for God and in Pre-Christian Intuitions.

“She used to come to see me as often as it was possible for both of us to fit it in. . . . With her extreme consideration of others,” Father Perrin added, “she used to wait quietly in the passage, letteting two or perhaps three people pass before her. After they had gone we talked for whatever moments remained. On a few rare occasions she asked me to see her at her friend’s house in order to have more time and freedom of spirit.”

quoted in Simone Pétrement, Simone Weil: A Life, New York: Schocken Books (1976), p. 412.

“Simone Weil spoke to Father Perrin about her Oriental studies, the Sanskrit texts she had been reading. . . . Father Perrin not only took interest in Simone Weil’s studies; he encouraged them. He also believed that her sociological theories were akin to certain new Christian ideas about the world of labour which were then gaining currency. It was for this reason that he asked Simone Weil to write her experiences as a factory worker for a publication he had in mind.”

Jacques Cabaud, Simone Weil: A Fellowship in Love, New York: Channel Press (1964), p. 253.

J.P. Little has noted that Solange Beaumier accompanied Father Perrin on his travels to Europe, North America, Brazil and North Africa and served as his “secretary and collaborator. . . .” She “also acted as his ‘eyes’ and generally organized his material existence, allowing him to lead a life of commitment that would not otherwise have been possible.”

On May 8, 1979, Father Perrin offered Pope John Paul II his autographs of Simone Weil. He also donated several of Weil’s texts — e.g. her commentaries on Pythagorean texts, her “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies,” and various notes on folklore — to the National Library.

He died on April 13, 2002, at the age of 96.

Select Books & Articles

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, preface, Reponses aux questions de Simone Weil, Paris: Aubier (1964)

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, Mon dialogue avec Simone Weil (Nouvelle Cité, 1984)

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, “A propos de Simone Weil,” Appendix I to L’Eglise dans ma vie, Paris: La Colombe (1951), pp. 117-124.

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, Mon dialogue avec Simone Weil, Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 1, no 1, juin 1978, pp. 2-12

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, Mon dialogue avec Simone Weil, Paris, Éditions Nouvelle Cité, coll. « Rencontres », 1984.

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, « Simone Weil au Portugal », Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 6, no 2, juin 1983, p. 135-136

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, « Simone Weil et sa recherche profonde », Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 12, no 3, septembre 1989,

- Joseph-Marie Perrin & Gustave Thibon, Simone Weil as We Knew Her (1953; Fr. 1952)

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, ed. & intro., Waiting for God (1951; Fr. 1950)

- Joseph-Marie Perrin, The Little Manual of Perfect Prayer and Adoration, Sophia Institute Press (2002)

- André-A. Devaux, « Joseph-Marie Perrin (30 juillet 1905-13 avril 2002), fils de saint Dominique et guide spirituel de Simone Weil », Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 25, no 3, septembre 2002, p. 255-266