The Merchant of Distraction: A Review of How to THINK Like Shakespeare

Ronald KL CollinsAttention is intimately related to desire — not to the will, but to desire.

Simone Weil, Notebooks, II, 57

Reading How to THINK like Shakespeare triggered a Proustian-like experience for me. Its initial lure took me back to 1968 when I first read Plato’s dialogues under the direction of Professor Michael Ormond. I had enrolled in his class on Plato’s Republic. Students were tutored in reading the full text carefully.

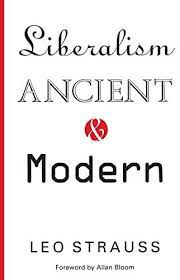

Several months later I drove out to Claremont College where I listened to a perceptive lecture on philosophy. While there, I purchased a then-new book, Liberalism: Ancient and Modern by Leo Strauss. In it was a chapter titled “What is Liberal Education?” All of which brings me back to that Proustian-like moment I recently experienced.

One of Strauss’ lines caught my attention, then and now: “liberal education consists in listening to the conversation among the greatest of minds.” (p. 7) To do that, Strauss stressed, one needed a teacher to introduce students to the great works of the greatest thinkers. In the process, he added, “we must transform their monologues into a dialogue, their ‘side by side’ into a ‘together.’” (ibid.) It was that dialogic engagement that first stirred my imagination and then seduced my mind.

One summer, about then, I ventured to Laguna Beach to participate in a reading group Mike and Jeanne Ormond had organized to discuss Plato’s Symposium. It was exciting to go to a Platonic party, one rich with ideas of the most tempting type. Rick, Dave and Stan were there as were others, including Aristodemus, Apollodorus, Agathon, Phaedrus, Aristophanes and Socrates. A mysterious woman was also there – someone Socrates claimed to have met once. Oh yes, Alcibiades was there, too; he burst onto the scene late and intoxicated. We interacted with them all, spontaneously and robustly. What a banquet it was, so much so that some fell asleep, though none in our Laguna group.

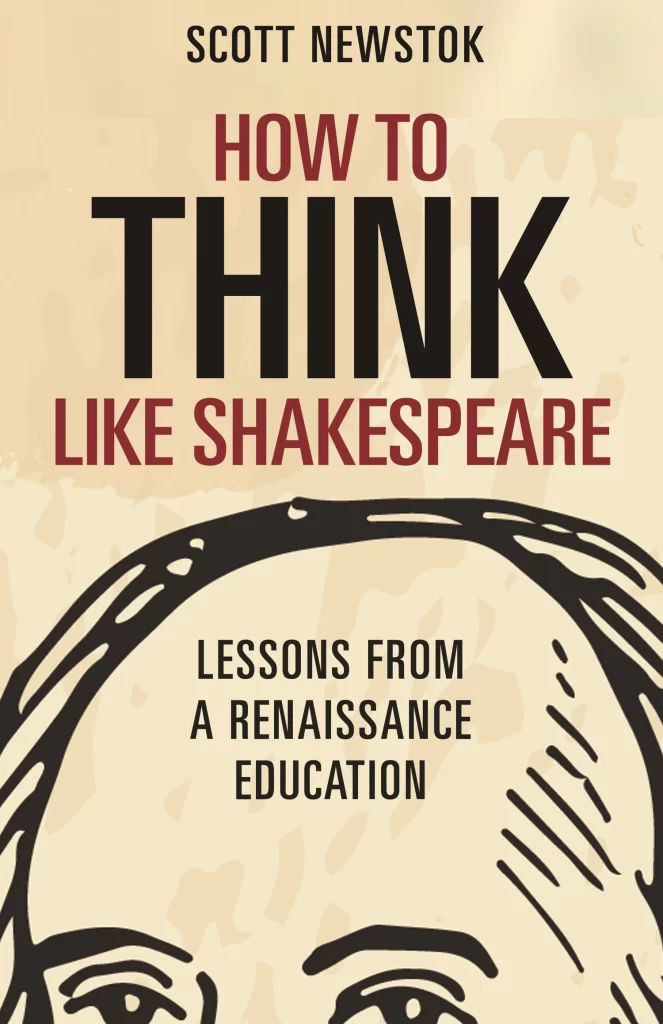

Memories now, but back then they set into motion a philosophic curiosity that continues to live within me. That is why I was drawn to Professor Scott Newstok’s How to THINK like Shakespeare: Lessons from Renaissance Education (HTLS), if only to engage him in a dialogue about liberal education. But that proved more difficult than the title of his book (with the word THINK in caps) suggested.

Let us begin by noting the brevity of HTLS (163 pp.) and the texts of its “deliberately short” 14 chapters that range from seven to eleven pages. Then there is the method by which Newstok (a professor of English) makes his case for thinking. By Shakespeare’s measure, this seems strange since Newstok’s bite-sized approach is one apparently designed for a Twitter-feed mindset.

On the one hand, HTLS is a work adorned with photos and stocked with snippet quotations and scores of footnotes regarding everyone from Erasmus to Wittgenstein, and with breakneck stops along the way to the likes of Virginia Woolf, Hannah Arendt, James Baldwin, and Bob Dylan, too. Additionally, click-click homage is paid to, among many others, John Donne and John Dewey . . . and, of course, to the Bard and his plays. In that sense, the book’s 14 chapters offer up tasty tidbits of notable lines of many great thinkers. Hence, its highly abbreviated form might well be characterized as the antithesis of the more learned lessons it claims to honor.

On the other hand, it could be argued that there is a certain realism at work in Newstok’s approach. That is, because he appreciates the severity of the crisis of modern education he addressed his audiences as he found them and not, instead, in the assiduous ways quietly counseled by Strauss. To that end, the modernist-like Newstok tantalizes his audience with the hope that his shortcuts might catch the mind’s eye of students waiting and wanting to think. The question then is whether the book is a realistic means towards greater ends or an end in itself. To be sure, it is a gamble of the kind found on a Las Vegas roulette wheel.

Moving to its substance, this book, prepared by the founding director of the Pearse Shakespeare Endowment at Rhodes College, might also be understood as a modern-day example of the very problem Allan Bloom pointed to in his blistering work The Closing of the American Mind (1987). Newstok’s offering is accommodating and egalitarian; it pampers the mind. It was just that brand of modern education that Bloom denounced in his attack on contemporary culture writ large. At a time when, as at Yale University in 2016, ever more students demand the “decolonization” of reading lists of white male authors, Newstok’s declaration is a daring one: “I am hopeful that Shakespearean habits of mind can help us hold a mirror up to current dogma.”

The promotional materials for HTLS assure its consumers that it is “[w]ritten in a friendly, conversational tone . . . brimming with insights,” and that it prompts “the thrill of thinking on every page, reviving timeless—and timely—ways to stretch your mind . . . .”

Yes, it is “friendly” if that means something other than demanding; and yes it is “conversational” if that is not synonymous with being dialogical; and yes it “invites the thrill of thinking” so long as the profundity of the Bard’s great insights about human nature is swept aside.

Newstok apparently understands the educational and cultural crisis of our times and how that problem is compounded by the alluring and habitual temptations of “smartphones.” Chapter 6, titled “On Attention,” makes that abundantly clear: “Too often these days,” he stresses, “our concentrated consciousness is taken, fractured by the merchants of distraction, who know that information-richness produces attention-impoverishment.” In that regard, he even quotes from Weil’s 1942 essay, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God.”

Predictably, the essence of Weil’s essay is entirely denigrated in the seven pages of text devoted to this subject. No fewer than 21 quotations – ranging from José Ortega y Gasset to Thomas More – dot the pages like dizzying flashcards whose truncated messages rush to the readers’ retinas with no real register. In the process, sustained attention succumbs to the demands of a “smartphone” culture. If, as promoted, such texts are “brimming with insights,” they are of such a nature that some students will be wildly confused while others will be hopelessly lost.

To further explore the nature of the problem under consideration, it may be helpful to leave modernity and return in time to what Niccolò Machiavelli penned in his famed December 10, 1513 letter to Francesco Vettori:

When evening comes, I return to my house and enter my study; and at the door I take off the day’s clothing, covered with mud and dust, and put on garments regal and courtly; and reclothed appropriately, I enter the ancient courts of ancient men, where, received by them with affection, I feed on that food which only is mine and which I was born for, where I am not ashamed to speak with them and to ask them the reason for their actions; and they in their kindness answer me; and for four hours of time I do not feel boredom, I forget every trouble, I do not dread poverty, I am not frightened by death; entirely I give myself over to them.

Since the subtitle of Newstok’s book claims to offer “lessons from a Renaissance education,” its readers would be well served to consider the words of this great Renaissance thinker. When Machiavelli returned to the world of those ancient thinkers, he engaged them and they him. Their minds joined with one another; the logos continued between the living and the dead; they occupied a space that was neither temporal nor predetermined, and their words “spoke” to him and he replied as if to breathe new life into them. Such was the back-and-forth of discourse between friends. Not only did Niccolò pass into their world, but they too into his. Metaphorically speaking, think of them waiting for him so they might escape from their tombs and enter the light of a new day, a thinking day.

But such educational engagement presupposes a certain kind of attentive reading that is neither abridged nor prepackaged. It means, at least at the outset, reading great thinkers on their own terms – fully, slowly, pensively, and with a passionate curiosity born of humility.

In an appendix to HTLS (titled “Kinsmen of the Shelf”), Professor Newstok writes of “shortcuts to knowledge” made possible by “handy” manuals, both “practical” and “portable.” By that measure, he tells us, he wants HTLS to be “handy,” a “handbook for the brilliant community” (quoting Dan Piepenbring’s “The Book of Prince”). Whatever else such a handbook for the “brilliant” might be, it would never be of the kind Machiavelli sought when he entered the courts of ancient thinkers.

In another essay in his Liberalism book Strauss cautioned: “Always assume that there is one silent student in your class who is by far superior to you in head and heart.” (p. 9) Thus understood, let us further assume that such a student broke her vow of silence and asked:

Professor Newstok, how would you respond to the assertion that the real educational problem is the result of the democratization of the university, of the relativity of all values, high and low, and of the debasement of knowledge? Is your book not painted on that very cultural canvas?

How might the good Professor reply?

In notable part, that debasement of thinking is due to claims of right – we are a rights-obsessed society. Everyone has rights, yet no one has obligations. What that means in a modern democracy is a fixation on entitlements of all sorts. In the process, colleges have become consumerist-oriented in that what is actually being offered is a saleable product of the kind that is most pleasing to consumers (once called students). “We want A and condemn Z” is the rallying cry of ever more young consumers who too often fail to appreciate the vices of A and the virtues of Z, if only because they view liberal education (improperly understood) as too demanding and too ill-suited to their expectations for job placement. It is those consumers (what Plato tagged “the Great Beast”) who determine what is offered in today’s marketplace of ideas.

Though there is some value in this little book, there is also much in it that is exaggerated – the title, the overabundance of quotes, the mind-numbing brevity, the excessive italicizing, and an animating sense of trying too hard to appease the consumer/reader rather than challenge her mind. In that regard, after studying its 163 pages one might rightly ask: what exactly does it mean to think like Shakespeare . . . as opposed to anyone else? Sadly, HTLS leaves that question largely unanswered.

Then again, it would be unjust to leave the matter there. Let us not speak falsely: these are hazardous times for institutions of higher education. Simply consider the skyrocketing costs of tuition, the vast cutbacks in the liberal arts departments, the runaway sense of student entitlement, the assault on traditional liberal education (an attack not without some merit), the so-called “cancel culture” mindset, the placement-office notion of education, and the politicization of the university itself. That is the world in which Professor Newstok finds himself, a world in which attention spans are synchronized with Twitter feeds. His educational experiment seeks safe harbor in that domain, to find a way to keep students afloat amid a tidal wave of cultural and technological distractions. Of course, and as Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once warned, sometimes experiments “based upon imperfect knowledge” fail.

In the end, How to THINK like Shakespeare is a most revealing tract on just how much modernity has changed even since that day in 1968 when I picked up a copy of Liberalism: Ancient and Modern.

Sources

- Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting).

- Scott Newstok, How to THINK like Shakespeare: Lessons from Renaissance Education, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (2020).

- Dan Piepenbring, “The Book of Prince,” The New Yorker (Sept. 2, 2019).

- Leo Strauss, Liberalism: Ancient and Modern, New York: Basic Books (1968).

- Simone Weil, “Reflections on the Right Use of School Studies with a View to the Love of God,” in Simone Weil, Waiting for God, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, Emma Craufurd trans. (1951), 105-116.