The Radical Weil and the Rightist Thibon: A First Set of Thoughts on “Gravity and Grace”

Ronald KL CollinsThink contrast and comparable. Think of opposites attracting one another. Now think of Simone Weil (1919-1943) and Gustave Thibon (1903-2001). In several significant ways, they were different, though the two friends relished the robust nature of their conversations. Simone was an intellectual who, among her many talents, read and translated ancient Greek and taught herself Sanskrit. Like Thibon, she valued intellectual discourse, albeit of a political and spiritual nature. Though he oversaw some twenty acres of farm fields, Thibon was very much a man of the mind. He was a country gentleman of the Saint-Marcel d’Ardèche region who appreciated the remarkable arc of Weil’s genius.

Radical and rightist friends, it is strange that the two ever bonded as they did. They were so close in some respects and yet so distant in other ways. In the evenings, after work in the fields and under the stars, Simone and Gustave allowed their friendship to blossom despite their differences. Their relationship gave contradiction new meaning.

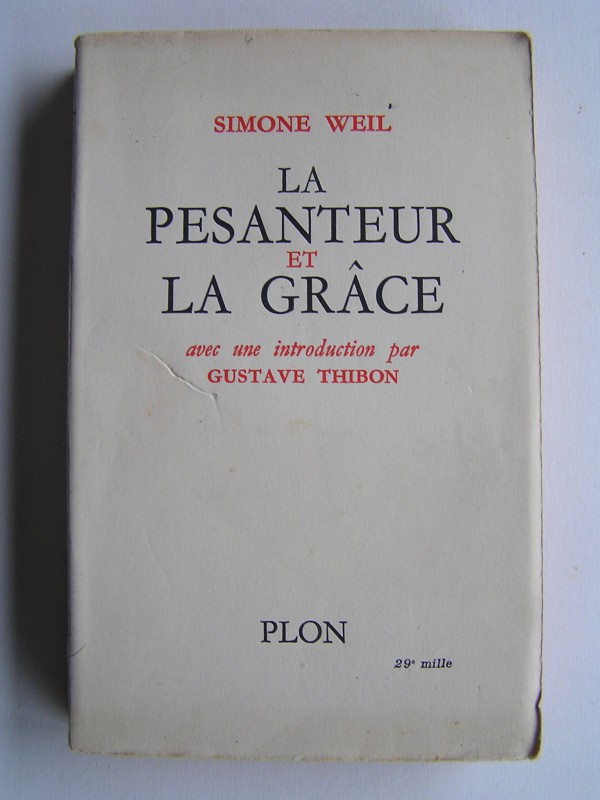

Thibon’s La Pésanteur et la grâce was released in 1947 by Plon, a politically conservative publishing house. By that time, he had already published no fewer than five books. One of those books, translated into English, was What Ails Mankind? (1946). It was a political tract staunchly opposed to political revolutions of almost any kind and highly critical of socialism and any form of social “leveling.” Thibon was a doctrinaire Catholic convert. Unlike Father Perrin (Weil’s other close friend), he had ties (disturbing though perhaps not extensive) to the antisemitic Vichy Regime and its leader Philippe Pétain, an authoritarian figure who in 1945 was convicted of treason. [Thibon, observed Francine Du Plessix Gray, “was one of Marshal Pétain’s principal speechwriters . . . .” Simone Weil: A Penguin Life, New York: Viking, 2001, p. 169]

Weil, by contrast, was a socialist radical with sympathies for revolutionary causes, though she always marched to the beat of her own drummer. What writings she published appeared in leftist labor papers and radical literary magazines. She was repulsed, as she judged it, by the Church’s history of political and religious oppression. Time and again, Weil was critical of the institutional and doctrinaire church and the repressive ways it responded to the spirituality of the “unfaithful.”

By the time she penned her notebooks, Weil was earnestly exploring the Manichean-Cathar culture and how it fell victim to the Albigensian Crusade and the Inquisition. Her sentiments in this regard might well be summed up this way: “The battle for bodies had been won; the next stage of religious warfare was the battle for souls. The Church could move from the conquest of a geographical region to the domination of the inner realm.” This historical fact galled her; it was a vicious sin for which Simone could never pardon the Church. [See Andrew Phillips Smith, The Lost Teachings of the Cathars: Their Beliefs and Practices. London: Watkins, 2015, p. 27 and Simone Pétrement, Simone Weil: A Life. New York: Pantheon Books, 1976, pp. 394-396] Since her ideas could sometimes be contrary to Church doctrines, that placed them outside of the Church.

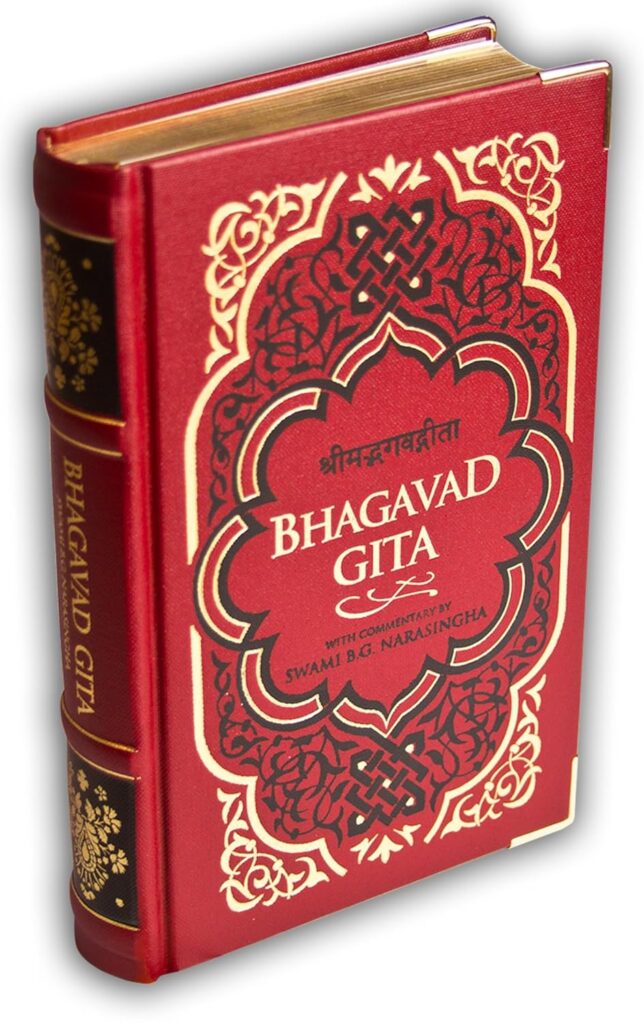

Yet there is more to say about Weil’s spiritual referents. One such referent is her 1942 and later interest in the Bhagavad Gita and Upanishads. In this regard, Norman Hendricks, in an impressive 1971 Ph.D. dissertation, has observed that Weil “assumes an authority for the texts which brings her close although not identical to a traditional Hindu. She demands that all great writing be given a degree of attention as if it were man’s sole access to truth. These texts are guides to [thinking] about the human condition because they are divinely inspired in the sense that their relationship is that of egoless personalities who because they are spiritually transparent allow truth to flow through them. The proof for her that they are divinely inspired is, in a sense, that they are anonymous. In this respect, she is close to Sankara’s doctrine of the impersonality and self-evidence of truth.” Simone Weil and The Indian Religious Tradition, Ph.D. Dissertation, McMaster University (Dec. 1971), p. 17 (footnote omitted). See also Maria Clara Bingemer, “War, Suffering, and Detachment: Reading the Bhagavad Gītā with Simone Weil,” in Catherine Cornille, ed., Song Divine: Christian Commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita, (Leuven, Peeters, 2006), pp. 69-89. While more will be said about this in future posts, the takeaway for now is that this tenet of Weil’s spirituality was foreign to Thibon and his doctrinaire Catholic thinking — hence, it received no direct and meaningful attention in his Gravity and Grace project.

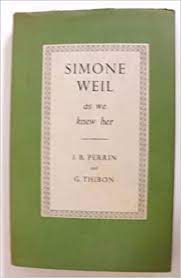

By Thibon’s gauge, Weil’s “categorical refusal of every truth which she had not elaborated and tested within her own mind” was a vexing flaw, especially when it came to Church doctrines. [Joseph-Marie Perrin and Gustave Thibon Simone Weil as We Knew Her, New York: Routledge (Emma Craufurd trans., 2003 ed.), pp. 112-113.] The institutional Church to which Thibon converted with such categorical devotion was the same one about which in 1942 Weil wrote this: “I am kept outside the Church by philosophical difficulties which I fear are irreducible.” (Richard Rees, ed. & trans., Simone Weil, Seventy Letters (Oxford University Press, 1965), p.155 {letter to Jeanl Wahl}). In so many ways, in Thibon’s own words, Weil was his opposite: “I had the impression of being face to face with an individual who was radically foreign to all my ways of feeling and thinking and to all that, for me, represents the meaning and savour of life.” (Perrin & Thibon, p. 109, emphasis added).

Given that, it is amazing that the two found any common ground, yet they did on certain matters. Their friendship was not shackled by their differences. Perhaps that helps to explain why Gustave Thibon, in his own sincere and respectful way, cast Simone Weil in his editorial image. The result was a work of brevity and ingenuity with a captivating air of Weilian authenticity. Thanks to Thibon’s handiwork, Weil’s words were made fresh both in form and substance. Whereas very few would ever read her complex notebooks (consisting of some 2664 translated and printed pages) in a comprehensive and reflective manner, very many read Thibon’s Gravity and Grace in a browse-and-sample manner, albeit with alluring Catholic overtones. The book invited readers into Weil’s world as seen through Thibon’s lens.

Make of his method what one will, but the fact remains that Thibon gave Weil’s words a popular reception they might not ever have otherwise enjoyed. His Gravity and Grace was an astonishing achievement, quite unlike other works with collected passages in posthumously edited books “by” other philosophers. Whether Thibon’s method could ever have won Weil’s approval as a book in her name is, in a certain sense, beyond the popular point – with its original 39 compressed chapters and aphorism-like appeal, Thibon’s Gravity and Grace has defined Weil for generations.

Gravity and Grace “fully belongs to the history of the reception of the thought of Simone Weil” — Robert Chenavier

Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 28, no. 3 (Sept. 2005)

When he first selected and then wove Weil’s words into his editorial plan, the result was to preserve his influence on those words since the two became one. Mass appeal greeted Thibon’s Gravity and Grace from the start. Many students and some scholars turn to it for guidance and even applaud its appeal. It has remained a book in spiritual vogue for over three-quarters of a century. For example, only two years following its release in France, Gabriel Marcel observed that La Pesanteur en la Grâce has made its way to all parts of the world and M. Thibon told me recently that he was receiving letters from everywhere, dealing with his work. A writer such as François Mauriac does not disguise his admiration for the book: a high destiny is undoubtedly in store for it. [“Simone Weil,” The Month, vol. II, no. 1 (July 1949), pp. 9-18.]

Likewise, in the United States, this history traces back some seven-plus decades. Consider the fact that in 1952 alone Thibon’s Weil book was favorably reviewed in the

- New York Times (Aug. 16 & 31),

- The New Republic (Oct. 13),

- The New Yorker (Sept. 6),

- San Francisco Chronicle (Sept. 7),

- Kirkus (Oct. 1),

- The New Stateman (Oct. 25), and

- Catholic World (Oct.), among other publications.

In that same year, there were even more articles about her written in the wake of Gravity and Grace: articles in such publications as the Saturday Review (March 8 & May 10), Catholic World (June), Theology (Aug.), Judaism (April), Cross Currents (Spring), and even in the Congressional Quarterly (July). In his 1952 New Republic review, S. M. Fitzgerald (a free-lance critic) predicted that “Simone Weil seems about to become a fashion, a rage. Among those who will talk about her there will inevitably be some to whom her subject doesn’t really matter as much as her vogue.” Only two years thereafter, in an essay in Catholic World (May 1954), Borisz de Balla confirmed what had already become in “vogue”: “The volume of interpretive essay-literature on her is now beginning to exceed that of Sartre” – and to make his case he pointed to Thibon’s “La Pesanteur en la Grâce.”

Ponder as one might about how to judge the collective appeal of Gravity and Grace, the conceptual die has long been cast. That is, Thibou’s book and Weil’s thought have become indistinguishably connected. Against that backdrop, Robert Chenavier’s point (in his article titled “Simone Weil, Author in ‘Some Way’ of Gravity and Grace”) rings true: They are, on the one hand, the actual works of Simone Weil, and other hand, they are her words as selected and structured in Thibon’s Gravity and Grace. Though the two were so different, the “reception of her thought” over decades has treated them as the same. What to make of that, of course, is another matter . . . about which more will be said later.

The above was excerpted from a much larger work still in progress. Additional installments from that work will be posted in future issues of this journal. — rklc

5 Recommendations