The Reluctant Witness: A Few Recollections of Simone Deitz and Related Matters

Jacques Cabaud“To have been Simone Weil’s friend can only bring unhappiness.”

— Simone Deitz (as told to me in reference to herself)

As we know from the innumerable films based in a court of law, some witnesses are too reticent, others are too talkative. Before the court of history, Simone Deitz, Simone Weil’s last best friend, was both. There was a reason for this, probably caused by a most disturbing event of her youth.

Deitz was 19 when engaged to be married to the son of a well-known professor at the Sorbonne in Paris. In those days Jews married Jews, even among agnostics. Simone Deitz must have been pretty attractive in the somewhat storied society of those days. That is when disaster struck: for reasons doctors must have found imperative, she had to have both ovaries removed. On the same occasion, her fiancé left her.

She belonged to the same generation as Simone Weil, though I suspect she was a few years younger. They met in Marseilles at a time when Simone Weil and her parents, as did many other Jews, tried to get visas for the U.S. circa 1941. Both families ended up in New York during the war years.

What is significant for our story is that by then both Simones, in their own way, had experienced that malheur (affliction) can lead to God. For Deitz, this had meant entering into the Catholic fold, whereas Weil, as we know, shunned a total commitment to which she considered she had not yet been called.

Archives Gallimard no longer exists)

Both Simones, however, shared the same patriotic spirit of dedication to the Free French movement with de Gaulle. They decided to apply for visas together. On their way to have their pictures taken at a photographic studio in the Rockefeller Center they entered an elevator in which, believe it or not, they ran into another Simone, namely “de Beauvoir.” This was an occasion not to be missed. As recounted by Deitz, Weil asked this ex-student of the Ecole Normale in Paris: “What is existentialism?” The unexpected answer was: “It is what it is.” With that de Beauvoir got out on her floor. Once she left the elevator, Weil commented to Deitz: “As you see, it does not mean a thing.”

Whatever one makes of the purported statement, we know that in Weil’s mind the great weakness of Sartrian existentialism was the omission of the notion of value.

The existential elevator story

This is but one of the many stories concerning her friend that Simone Deitz told me once we met in 1957. Since this one sounded too good to be true, I wrote a letter of inquiry to Simone de Beauvoir — wisely omitting her comment: “It is what it is.” Her answer was indignant: “How could I have been during the war years both in Paris and in New York?” My excuse was that I had not yet read her own biography. Thus did I begin to have my doubts about the reliability of Simone Deitz.

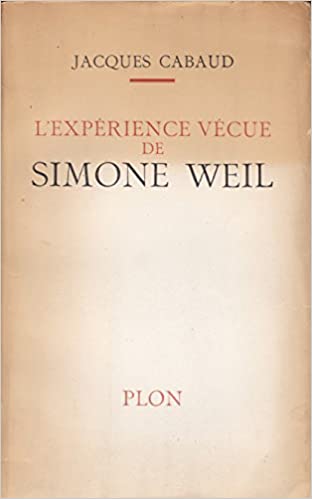

She had contacted me first. She had read my book L’Expérience vécue de Simone Weil (Plon, 1957) and must have been astonished that I, as her friend’s biographer, had neglected to take the initiative to meet her in person. Nobody’s perfect! Furthermore, Mme Selma Weil had warned me: “Simone Deitz is a mythomaniac”. Would that I had taken this statement literally.

Graduate thesis — off to Paris

To turn the clock backwards: Once I had completed my graduate studies in French Literature at Columbia University in June 1950, I asked my favorite professor, Jean Hytier, if he would sponsor my proposed thesis “Pascal mystique.” He agreed, and I left for Paris where I stayed for three years.

Soon after my arrival, I came upon a newspaper review by André Rousseaux on Simone Weil’s Attente de Dieu (Waiting on God), which Plon had published. A year earlier, I had perused à review of La Pesanteur et la Grâce (Gravity and Grace) that left me unconvinced. But the quotations from Attente made such an impression on me that I knew I had to explore this terra incognita. This struck me as preferable to paddling through the bibliographical morass of past scholarship such as would have been the case with Pascal. My reaction was: “They are both mystics, and she writes as well as he did.”

Novelty is attractive per se: the name of the Dr. Bernard Weil family was in the phone book. When I arrived at her door, Madame Selma Weil greeted my project, La Vie de Simone Weil with the warmth of a mother totally focused on the posthumous reputation of her daughter. None of the then-available biographical accounts had the format of a doctoral thesis.

I borrowed my sister’s Solex, a motorized bicycle with a top speed of 25 km an hour and interviewed all the people who to my knowledge had met Weil, whether they lived in Paris or in other parts of France where Simone had taught or spent her holidays. Many of her manuscripts were still unpublished: I remember copying pages upon pages by pencil at the Bibliothèque Nationale, where Simone Weil’s friend, Simone Pètrement, an archivist there, was of great help. (Her two-volume biography, which appeared ten years after mine, is the most complete and the most reliable work on Simone Weil.)

Pètrement and Madame Weil referred to me as “le détective” because, in my blissful ignorance of the rules, I had a few times obtained access to data that should have been archived out of sight for fifty years. It was really nothing else than “beginner’s luck.” I interviewed some big names, like Maurice Schumann who received me in an office as large as those you see in historical films, where I committed the “faux pas” of not waiting for the uniformed usher to guide me out the door.

In the course of my many visits with Madame Selma Weil, the name of Simone Deitz came up. It was from Selma that I heard of Deitz’ surgery and broken engagement. This tragedy must have been the reason for the onset of her mythomania, a rare condition, which led her to report falsely about past events without realizing herself the difference between fact and fiction.

Hence, I should have explored this matter. Since Deitz lived in the States, however, at that time I put her on the list of persons to be interviewed.

Meeting Simone Deitz . . . in New York

Since the mountain would not come to Mohamed…. It is not, however, as if Simone Deitz needed my doctoral thesis published by Plon in 1957 to become aware that her name would be associated for centuries to come with the last two years of a potentially immortal figure. She was then teaching French and French Literature in a women’s college in New England. She called me on the phone and we agreed to meet during her next visit to New York.

Simone Deitz had an engaging personality. I like to categorize people by their most obvious character traits. Gustave Thibon and Albert Camus (the latter whom I only met once and briefly) both impressed me with their quick minds. The Thibon-Weil discussions in the Fall of 1941, which were endless, survive only in Thibon’s published works.

When I interviewed Georges Bataille, whom Simone Weil considered an “obsédé sexual,” found nothing better to mention other than he had lent her an erotic book, not that she had asked for it — La bouche parle de l’abondance du coeur. Out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaks [that’s a quote from Luke].

In the case of Simone Deitz what she said was colored by what she had gone through herself. How could it have been otherwise? But at first I did not notice that this quality of subjectivity was at work to such a high degree. Still, I was enchanted by the vivid way in which she recounted the hours she had spent with Simone Weil.

Later, when I wrote her a letter of thanks, I mentioned we should write a book on our common object of interest. It was clear she did not wish to do so on her own. I admired her modesty, unusual as it may seem on the part of the would-be scholar usually lurking below the college teacher.

Time went by and I added some of what she had told me to the nearly finished typescript of the translation of L’Expérience vécue which would appear as Simone Weil: A Fellowship in Love with Harvill Press. The second part of the book was stylistically uneven so that I had to rework it with the help of an English Graduate student (Janet Egleson), while incorporating some of Simone Deitz’s souvenirs.

“Erroneous reminiscences”

Rereading the text now, I noticed two passages that I am certain are Simone Deitz’s erroneous reminiscences:

- on page 294, Simone Weil’s parting words to her parents (I underline the emphasis): “If I had several lives, I would devote one of them to you. But I have only one, and I owe it elsewhere.”

The underlined passage was added by Deitz and did not feature in Selma Weil’s recollections. The reader will appreciate, however, that the addition was already implicit in Selma’s shorter version.

- on page 325: ” . . . once when boating with Simone Deitz, [Weil] teased her by rocking the boat until they both fell into the shallow waters of the Serpentine”.

Years later I met the lady who had been responsible for this incident in which Weil had not been involved.

In all the other passages, where Simone Deitz is alone with her friend, I have to leave it to the reader’s personal wisdom and sagacity to determine what is true and what isn’t. How does one decipher fiction from fact?

With Simone Deitz, fiction is often plausible enough. Were she still alive, I doubt she could be of any help, since she would not be able to distinguish between the two.

I remember her astonishment when I reported to her that de Beauvoir had written that she could not have been in New York during the war years: “I was convinced indeed it was her,” was Deitz’s response.

Co-authorship?

I had kept Simone Deitz posted on the forthcoming publication of A Fellowship of Love. That is when she called me with the following proposition: “Since you asked me to collaborate with you on a book on Simone Weil, this is the occasion to do so. I still have your letter. Since the administration at my college is threatening me with a non-renewal of my teaching contract, I need to write a Ph. D. Thesis or at least some kind of equivalent publication. I am sure that my collaboration with your future book would pass muster.”

This sounded to me as nothing short of proposing a fifty-fifty sort of writing arrangement. Jacques Cabaud & Simone Deitz — a masterpiece? But when I calculated the matter in my head, I realized her contribution to my forthcoming book constituted, at the utmost, 12 of the 384 pages, and in many cases not her alone.

Considering the amount of information I had obtained from Madame Selma Weil directly, it is she who would have deserved credit as a co-author, even though she had not permitted me to make notes when she spoke to me — a clear sign she did not consider herself a co-author. She treated me like all the other innumerable students or literati who came to her for information about her daughter.

Believe it or not, faced as I was with what amounted to the partial surrender of authorship, I thought of Christ’s words: “If someone asks you for your cloak, give him also your tunic.” Since I am not made of the same stuff as St. Francis of Assisi, I balked.

But Simone Deitz was insistent: “I have it in black and white in your letter concerning the proposal of the co-authorship I deserve”. This is in substance how she argued.

I answered I would mention her contribution to the extent that I felt it could help her to obtain tenure. For this is what the whole thing amounted to.

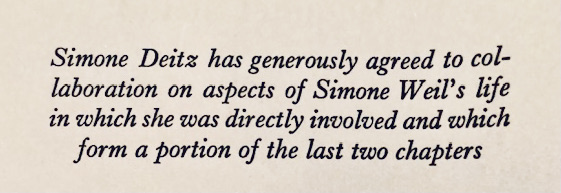

I struck a balance between gratitude and integrity, which somewhat strained my conscience. I hoped the formula I found could pass off as a white lie. It is what you can read on the fly-page of A Fellowship in Love in the small print (see immediately below), and in the larger print in the first paragraph of the Acknowledgement (see second excerpt below).

Half-measures are doomed, of course, as they should be. Thus, Deitz had to take a leave of absence of one year to write a doctoral thesis in France. She thereafter secured her position. She must have been a good teacher: her department appreciated her.

Had someone actually baptized Simone Weil?

Later I heard that at the University of Quebec (a religious institution) a student had mentioned to a professor that she had baptized Simone Weil. Since I did not know that Deitz had studied at Quebec, I borrowed a car from a friend and drove there to learn more about this story. I interviewed no fewer than three professors who were three priests, all of whom received this information from “the horse’s mouth” — Simone Deitz.

The question in my mind was then: “Why did she not tell me about this?”

As chance would have it, I met Deitz in the New York subway. She did not seem astonished at my blunt question: “When did you baptize Simone Weil? Was it in the Middlesex Hospital in London or shortly before her death at Ashford Sanatorium?”

Her answer was “I cannot remember, the times were so strenuous, I do not know for sure.”

I was somewhat flabbergasted but did not express it. How often, indeed, does a layperson find herself in the position of administering the sacrament of Baptism? I had never met anyone until then who had done so. I should have asked, in circumspect terms, if Deitz had suffered from shell-shock during the war she had participated in. But of course, I did not.

Strange & strained times

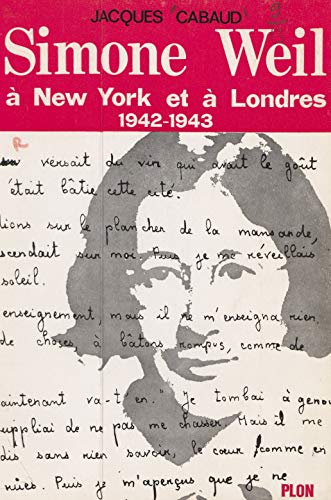

I called Simone Deitz on the phone to tell her about my forthcoming book, Simone Weil à New York et à Londres: les quinze derniers mois, 1942-1943 (Paris: Plon, 1967). Among the random things she said was the following: “As for the Catholic Church, I am on the way out.” I should have queried what were her grounds for doing so. Her feeling of relief at leaving the Church was intriguing.

Leaving the Catholic Church issue aside, I asked if she would read my typescript: I wanted to know if she agreed with the way I reported the role she had played in Weil’s life. Her answer was curt: “Send me a letter about this matter.” Instead of saying a few placating words, I retorted spontaneously: “Considering the way you use the letters one writes to you, one hardly feels inclined to do so!” She did not leave me the time to present my excuses for being impertinent. She retorted: “In that case, the answer is no.” Click.

Up to then, we had been on good terms. The mood seemed to have changed all of a sudden. She was no longer the same. What about me? Our friendship had been a bit strained at times.

I should have been wary after this and changed the single word in my text which Deitz would be bound to find offensive: On page 35 of Simone Weil à New York et à Londres (Paris: Plon, 1967), I wrote: “Simone Deitz rayonnait de vie, d’entregent, d’exubérance/” That second word was questionable. According to the dictionary, “rayonnait de vie, d’entregent, d’exubérance” means that she “radiated life, the ability to manage people, and exuberance”. The meaning I had intended to convey was that she was “ingratiating,” and not that she was sly. I guess my subconscious must have played me a trick. Writers should be wary.

An indignant letter

The rest is history. Later, I received an indignant letter from Deitz. Her colleagues in college had been chuckling over her “entregent” (interpersonal skills). She stated that for this defamatory injury she was claiming damages for $135.000.

I should have written a letter of apology. Since the claim for damages was so preposterous, however, I did not respond. The matter had taken such unreal proportions!

Three weeks later I received a letter from my publisher in Paris — Plon: the editors were being pestered by letters from Dr. Deitz who complained that I was not answering her mail. Since they, as publishers, had to take notice, should I let them know how they should answer. My answer was that “I offered my manuscript for approval to every one of the public figures mentioned in the book, Maurice Schumann, André Philippe, André Weil, etc., but Dr. Deitz is the only one who turned down the offer.”

In conclusion, this question of Simone Weil’s collaboration with A Fellowship in Love was based on a misrepresentation, obtained under false pretenses, for no one’s advantage or profit, and which should be relegated to a dustbin of scholarship.

It had been “Much ado about nothing”.

A few closing thoughts

All said I wish, nonetheless, to take this occasion to bow my head before these two Simones who lost or risked their lives for their beloved country.

Risk-taking was part of life in those days. That is why Simone Weil could define “risk” as both a personal right and a social duty in her “Projects for the future Constitution of France” — “Risk is an essential need of the soul”. Today when the State has become a Nanny-State in many countries, we are robbed of our birthright: that of meeting on our own the challenges of life and responding freely to the values “which are not of this world”. Simone Weil thought scholars could find in the past the answer to our quest for a meaningful future.

Regarding the nature of this answer, she pursued an endless debate with the priests she met. She had found for herself a home “in the love that forever holds us in His arms.” To Providence who had sent her “the gift of suffering”, she responded with the simplicity of spiritual childhood. Her brother, who remained an agnostic, once qualified his sister with the words that should terrify our lukewarm faith: “She was born a Saint”, and then he would add: “Just as I was born a mathematician.”

The parallelism would last as long as they lived: André’s choice to refuse the call to arms of the French army, the better to pursue his algorithmic inquiries; her attempt to infiltrate enemy-occupied territory, the better to be caught . . . or what was it that she pursued in her need for the greatest danger, if not to give up her life so that others may survive, a truly Christ-like resolve?

— Jacques Cabaud has authored three books on Simone Weil:

- L’Expérience Vécue de Simone Weil (Paris: Plon, 1957)

- Simone Weil à New York et à Londres : les quinze derniers mois, 1942-1943 (Paris: Plon, 1967) and

- Simone Weil: A Fellowship in Love (UK: Harvill Press, 1964)

Related

— Andre A. Devaux, “De Marseille à Ashford, le singulier compagnonnage de Simone Weil et Simone Deitz” (“From Marseille to Ashford, the singular companionship of Simone Weil and Simone Deitz”), Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 22, no. 3 (1999), 315-320.

5 Recommendations