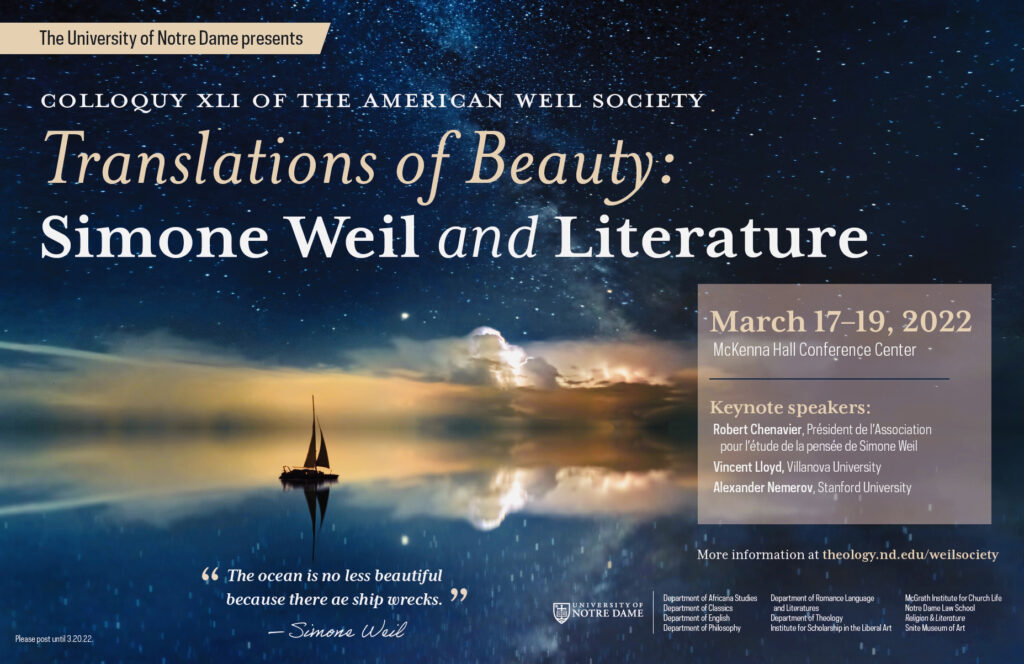

“Translations of Beauty: Simone Weil and literature”: The 2022 American Weil Society Colloquy, Part II — a Summary

E. Jane Doering

Introduction

According to Simone Weil, contemplating the works of authentic geniuses of past and present is an inexhaustible source of inspiration, which can legitimately direct our thinking. This inspiration, for those who know how to receive it, expands, as in Plato’s image, into wings against moral gravity.

The works of authentic geniuses, whether they craft their message in words or visual images, aid in the task of consciously decentering the attentive person away from being the center of his or her own imagined universe and toward a transcendence or an assimilation with God. Contemplating varied approaches to such an essential goal by fine minds of the past and present motivated the thoughtful papers and panels described in Part II of the summary of the 2022 American Weil Society XXII annual colloquy organized by Professors Ann Astell and E. Jane Doering.

Giotto’s Portrayal of St. Francis

Initiating the 2022 Friday series, keynote speaker Alex Nemerov, renowned art historian from Stanford University, explored Simone Weil’s reaction to seeing Giotto’s portrayal of the life of St. Francis during her 1937 trip to Assisi and Florence. Weil wrote that Giotto’s painting is an expression of holiness; she later reaffirmed the idea that the art of Giotto was not unconnected to the Franciscan spirit. Sharing illustrations of several of Giotto’s paintings, Professor Nemerov focused on the artist’s placement of St. Francis slightly off center, leaving a space or a void in the center as an emptiness through which God enters. Similarly, St. Francis’ relationship to the institution of the Church—being both part of and yet separate from—is also expressed visually in his separate stance vis-a-vis church structures.

Nemerov reminds us of Simone Weil’s essential belief: “To give up being the center the world in imagination, to discern that all points in the world are equally centers and that the true center is outside the world, this is to consent to the rule of mechanical necessity in matter and of free choice at the center of each soul. Such consent is love.”

Referring to Giotto’s prayerful relation to the beauty of nature, Nemerov recalled Weil’s conviction that every true artist has had real, direct, and immediate contact with the beauty of the world, contact that has the nature of a sacrament. In the Sermon to the Birds, St. Francis has come across a flock of birds that does not fly away at his approach. He gives a sermon to the expectantly waiting creatures, who leave only after receiving his blessing. Giotto makes plain the extraordinary nature of events through the reaction of the Franciscan friar, who raises his hand in surprise to accentuate the scene’s unusualness. Once again, Saint Francis is decentered but the implied words in the center could represent an emptying of oneself. The descending bird suggests free choice in the center of the soul, while in the background, the pods bursting open in the trees reveal nature’s complicit ecstasy.

Weil’s ideas and contemporary dilemmas

We also rejoiced in the success of the pioneer hybrid format, seamlessly aided by Richard Allen, the University of Notre Dame’s streaming engineer, which permitted worldwide representation and myriad fresh perspectives on the religious philosophy of Simone Weil. The goal of this two-part summary is to encourage continued discussion of the diverse topics; readers can access any full paper or even better start a dialogue with other Weil scholars, by finding email addresses through university websites or inquiring through the AWS website, where recordings of the keynote speakers and the Friday series panels are accessible.

In evidence throughout the colloquy was an intense interest in exploring the applicability of Weil’s ideas for fresh perspectives on resolutions to contemporary dilemmas, which would require, among other things, emptying oneself to give full attention to the reality of the other, including nature. The topics treated here include the transformative roles of justice and liturgy, Weil’s rights critique, contradiction as transcendence in “Venise Sauvée,” Meister Eckhart’s approach to decreation juxtaposed with Weil’s concept, decreation and recreation in the Anthropocene, Weil’s reading of the Hebrew Bible, theology seen through the lens of Weil’s thought, and varying philosophies behind translating Weil’s works.

Jesse Perillo of De Paul University spoke of justice as a liturgical form of life, which focuses on lives lived in relation to others, just as liturgy functions as a means of transforming hearts. This attitude is contrary to the mindset inspired by the language of Rights. In the contemporary dialogue about liturgy’s connection to politics and ethics, the necessity of justice as a performative form of life becomes evident. Viewing Weil’s work on justice through a liturgical lens highlights aspects of Christianity’s own idiosyncrasies. Her resistance to the transformation of justice into a mere principal to be applied or into a practical means to solve a problem stems from the conviction that a disembodied Rights discourse becomes immune to the suffering of the body.

Päivi Billie Gynther, a freelance researcher in Finland, also revisited Weil’s Rights critique by comparing the thoughts of Simone Weil and Christos Yannaras, a Greek philosopher known for his critique of individual rights. Placing both philosophers in conversation, Ms. Gynther discussed six points: how rights-language feeds self-centeredness, creates deceptive categories of concern, offers a false image of freedom, defeats communities, remains insufficient in terms of vocabulary, and most essentially molds a hegemonic paradigm. Gynther posed the question of whether the language of human rights as a global lingua franca could ever rise above the level of a dream. She concluded with the pertinent question: “What are the creative alternatives?”

Alejandra Novoa of the Universidad de Los Andes, Chile, continued the concern for the social good with a presentation on Simone Weil’s portrayal of contradiction in her literary opus of poems and a play, “Venise Sauvée.” For Ms. Novoa, Simone Weil’s use of contradiction in her literary work illustrates the concept of bridges or metaxu as a means to transcendence or to a greater assimilation with God. Thus, when the sacrifice of Weil’s protagonist Jaffier is perceived as an offering rather than an annihilation, another access to truth is revealed. Essential to Weil’s religious philosophy is the understanding that by accepting sacrifice for the good of others as a bridge to the transcendent, societies as well as human beings can rise to a supernatural destiny.

Considering the suffering of affliction as a compelling force toward decreation, or emptying of self, Sarah Griffin of Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada, presented a comparative study of Eckhart’s theory of “ground” and Simone Weil’s theory of decreation. Ms. Griffin maintains that placing Eckhart’s detachment next to Weil’s concept of decreation not only substantiates the current understanding of Weil’s mystical impulse but supports the distinctly tragic aspect of her Christology.

Kate Lawson of Queen’s University confronted the tragedy of climate catastrophe in her discussion of ethics and beauty in the Anthropocene. Ms. Lawson expands Weil’s ethics to include the “natural world” and applies her attention to art, science, and work, as three actions that allow for human creation. Any ethics suitable for survival in the face of our present species extinction and human annihilation must include Weilian decreation as a prerequisite to allow for an innovative recreation. Decreation and recreation are two sides of the same coin in Weil’s concept. In the present dire necessity for creative thinking, Ms Lawson reiterated Weil’s reflection that the best time to be alive is when radical new possibilities become the indispensable imperative.

With his provocative title, “Translating Silence: Delores Williams and Simone Weil on ‘The Underside of the Underside,’” Mac Loftin, a Harvard University Ph.D. candidate, offers a fresh look at Weil’s critique of the Hebrew scriptures. On reading Weil and Williams together, Mac Loftin assumes the seriousness of Weil’s judgmental commentary, while at the same time showing how she failed to see that her critique is, by her own criteria, evidence of their beauty and truth. Hagar’s story and the Book of Joshua held the attention of Weil and Williams, the first as a beautiful and pure part of the Hebrew Bible and the latter as an example of biblical authors misidentifying genocidal ambitions as God’s will. Loftin sees the internal contestations in the Bible as signs of vulnerability and thus evidence that God has consented to have God’s story told by fallible creatures who will inevitably fail in the telling.

Winch & Weil

The final event of the in-person part of the colloquy was a hybrid panel exploring Peter Winch’s 1989 classic philosophical work, Simone Weil: the Just Balance. The participating philosophers: Eric Springsted, Chair; Mario von der Ruhr, Emeritus, Swansea University, UK; David Cockburn, Emeritus, University of Wales Trinity St David, UK; John Edelman, Emeritus, Nazareth College, Rochester, NY, explored Winch’s reading of Wittgenstein and how it might have informed his interpretation of Weil. The panelists would gladly entertain additional questions and comments on Peter Winch’s study of Simone Weil.

Translating Weil

Just as Simone Weil believed that eternal principles must be transposed for each new period or generation, her writings must also be translated into other languages with diverse cultures. The Friday series panel on the pleasures and pitfalls of translating Simone Weil dealt with varied conundrums that inevitably confront the most experienced of translators. Three current translators of Simone Weil’s works: Ros Schwartz, presently translating Weil’s L’Enracinement for Penguin UK and Philip Wilson and Silvia Panizza, both translators of Weil’s Venise Sauvée and her poems for Bloomsbury Press, and moderator Tess Lewis, an internationally recognized translator, focused on the varied philosophical approaches that guide translators.

All agreed that the intellectual effort of carrying over the meaning of a literary creation from one culture to another requires humility, attention, patience, and an emptying of self in the attempt to remain consistently faithful to the author’s intentions. Good translations are the result of collaborative efforts that deal with the conflicting voices and contradictory ideas while keeping the author’s rhythm and images. So that a reader remains ever mindful of the task of translating while reading a work from another language, the translator’s name should be prominently displayed.

The challenge of seamlessly maintaining the many cultural, historical, and political references for readers of other cultures and not resolving what is left unresolved by the author are ineluctable constraints. As Philip said, “What is ragged should remain ragged.” That Weil considered the above works as unfinished, ever honing even the wording of her poems, gives an added hurdle to making her work accessible to another culture.

We are very grateful to the panelists for sharing their trials and provocations in translation; we recommend to our readers the full recording of their fruitful exchanges, easily accessible on the AWS website.

An additional advantage of the new technology that allows voices from around the world to be heard by offering a forum to Weil scholars at all points in their study of her religious philosophy was demonstrated in the final Friday series panel. Five young Weil scholars from vastly different areas shared diverse results from their periodic “think tank” Zoom meetings in which they discuss their incorporation of Simone Weil’s unique thinking into their theses, sermons, and teaching. Tom Sojer of the University of Erfurt, Germany, Emily King of the University of Chicago, Gwen Dupré, of the University of Oxford, Joanna Winterø from the University of Copenhagen, and Mac Loftin, of Harvard University, dealt individually with the political aspect of theology, theology as a process of unlearning, discrimination in the Christian churches, the need for attention, openness, and compassion to facilitate true love of the other and a permanent refusal of the use of force. They invite Christianity to embrace the continuance of change.

We were happy to hear both Emily King and Mac Loftin earlier in the conference. We hope the other panelists will propose individual papers for the 2023 colloquy, particularly in view of Gustavo Gutiérrez’s invitation to see theology as a reflection of life in light of the reality of God, which echoes the religious philosophy of Simone Weil.

Ann Astell and I are grateful for the notes expressing appreciation of the hybrid format:

The Web series that followed the conference is a wonderful way to connect with Weil scholars overseas and to continue the conversation after the close of the conference. I hope that the Society continues to expand the conversation beyond conferences!

Many warm thanks to the organizers and executive committee for a wonderful conference and for transitioning into more accessible formats for sharing Weil’s incredible ideas.

I am grateful that you both have worked diligently to present this year’s colloquy in the hybrid format. I have such fond memories of attending these in person – my first was Toronto – how meaningful it has been to connect with others who share my passion for and commitment to Simone Weil’s life and work. I’m glad for the seminars planned for three Fridays, too.

I have appreciated being welcomed into this extraordinary community despite my lack of a university position. Even with my entry and participation as an unaffiliated independent scholar, I have always felt included. Such generosity.

Just a quick note to say thanks for everything! Got lots of food for thought, and AWS civilizes me!

And to visit the beautiful campus of Notre Dame and to be hosted by you, to encounter that huge gift of hospitability. I find no words nice enough but to repeat my thanks. I will stay in touch.

4 Recommendations