Weilian Models for Living: 2022 Colloquy of the Association pour l’étude de la pensée de Simone Weil

E. Jane DoeringPERSONNEL/IMPERSONNEL, INDIVIDU/COLLECTIF

The 2022 colloquy of the Association pour l’étude de la pensée de Simone Weil was held in Angers, France, at the Hostellerie du Bon Pasteur over the weekend of Oct. 29-30, 2022, on the topic of “Personnel/Impersonnel, Individu/Collectif.” This international Simone Weil association is presently entering its 47th year, having nourished manifold Weil scholars after being founded by French scholar André Devaux almost half a century ago. The American Weil Society, inspired by the original Weil Association in France, had its beginning shortly thereafter.

President Robert Chenavier, eminent Simone Weil Scholar, editor of the Cahiers Simone Weil and of the Simone Weil: Oeuvres complètes, and editorial secretary Marie-Noëlle Chenavier welcomed approximately 50 participants representing France, Italy, Spain, Wales, Mexico, and the U.S. Through the lens of three of the sixteen presentations given over the two days, we offer a glimpse into the depth of thinking that took place on this key theme in Simone Weil’s religious philosophy; all talks will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Cahiers Simone Weil.

Angers, the historic capital of the province of Anjou, situated at the confluence of the Loire River and the Maine, is graced with a gentle climate and awarded the title of “Ville fleurie.” Extensive fields of beautiful flowers supply plants and cut blossoms throughout France. The massive Chateau fort of Angers, constructed with its locally mined black slate and white tuffaut stone, was begun in the 9th century and fortified with thirteen massive towers up through the 13th. These monumental round towers were originally one third higher and coiffed with conical rooves until Cardinal Richelieu (1585 – 1642), bent on centralizing the French State under Louis XIII, ordered its dismantling, a hated order, happily and immediately nullified at his death.

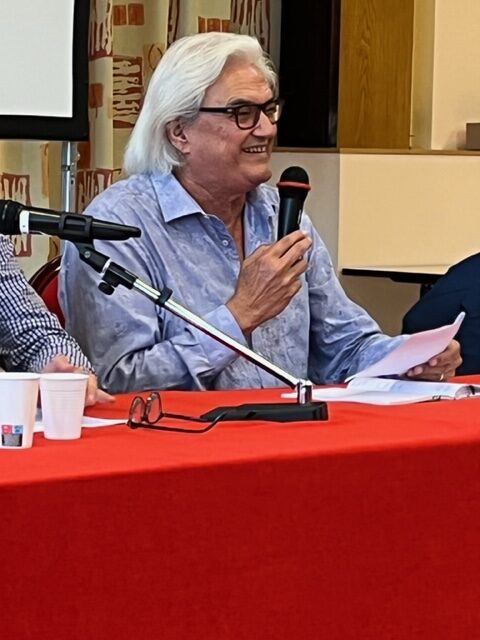

Robert Chenavier: Introduction & Opening Remarks

In his introduction, “Mettre en relation: la Personne, le Collectif, le Commun, la Limite,” Robert Chenavier, spoke about Weil’s project, noted in the London Notebooks, to write on the notions of “Collectivité—Personne—Impersonnel—Droit—Justice.” These insights were later published posthumously under the title “La Personne et le Sacré.” Her first caption had been: “Faut-il conserver le vocabulaire personnaliste?” The Gallimard Press, committed to making available to Weil scholars all her written notes—down to the slightest fragments and doodles—has been compiling sixteen volumes under the rubric: Simone Weil: Oeuvres complètes, of which twelve are already in bookstores. Nevertheless, as Robert Chenavier wryly observed in his presentation, Weil scholars are left with the fascinating task of unraveling her many seemingly contradictory strands of thought, all interwoven like skeins of wool. This recent conference offered a prime example in the challenge of illuminating her understanding of the relationship between the personal, impersonal, and the sacredness of the human person.

In his opening remarks, Chenavier set the tone by elaborating the paradoxical and obscure in Weil’s citation: “Lectures superposées: Il faut aimer Dieu impersonnel à travers Dieu personnel” from her Notebooks. [Note: “Superimposed readings: one must love the impersonal God through the personal God.” All translations are mine.] He pursues his analysis by distinguishing between the political and the social spheres and that of the person. Divine limitation, self-imposed by God, a paragon for the human person, can also be an exemplar for the social sphere, a win-win for everyone.

Chenavier cites Gaël Giraud, an economist and Jesuit, along with the jurist Alain Supiot, who claim that it is within the sphere of each person to take on a sense of the divine auto-limitation as a key to optimal relationships, which would allow the common good to gain primacy of place. Weil cautions us that such a goal would take a great deal of work, for the unfortunate reality is that personhood, or personal identity, becomes inappropriately inflated when social prestige is at play. (See Francesca Simeoni below for explicit examples.) The relevancy of Weil’s concepts for today was apparent throughout the presentations.

Francesca Simeoni

The obligatory work on the self by the individual is a major theme in « Quelle anthropologie pour l’impersonnel » by Francesca Simeoni, a young Italian philosopher presently at the Université Catholique de Lyon. Maintaining her thesis that there is common ground between the personal and the impersonal in Platonic philosophy, she draws her conclusions from two of Weil’s 1929 essays, “Du Temps” and “Le Travail comme médiation.” Modern society, with selfies and internet posts for personal expression, has eliminated many former obstacles that slowed down the process of knowing oneself by facilitating a speedy but superficial process of self-knowledge. This demand for immediacy in self-expression tends toward conformity, a willingness to plunge into the collective, a propensity feared by Simone Weil. She insisted that true authenticity of self, on the contrary, came only by way of mediation and a tortuous learning curve passing through vulnerability, powerlessness, and affliction.

Post-modern attitudes are impelled by rivalry and by denial of one’s neighbor in the cry “Why does the other have more than I?” On the contrary, the impersonal corresponds to full acceptance of the reality that “there is nothing in me that I can lose,” a humbling humiliation that permits hearing both the affliction of the other and the truth. This state of susceptibility requires a contraction of the power of the ego. According to Simeoni, Plato’s psychology, as expressed in the “Banquet,” in which the soul is essentially animated by eros: eros of tyranny and eros of Beauty, is inherent in Weil’s understanding of human nature. Desire can be domineering, based on avidity for power, consumption, and property wanted immediately and in abundance, despite the cost. Alternatively, desire without a specified goal is pure and active receptivity, transforming itself into transcendent action based on the real, on love.

Simeoni concludes that an anthropology centered on the soul and on a metaphysic of mediation enables living the impersonal as imagined by Weil. The “I” or self, has the possibility of accessing several levels of mediation in the impersonal, including the full void, which opens the way for the good. Nevertheless, the inexhaustible spirituality of desire, sacred in all persons, requires nurturing through education, work, courage, determination, and protection by a political system that is too often tainted by egocentrism.

Rita Fulco

Weil’s warning to her students that going against society is rare and takes great courage is reiterated by Rita Fulco of the University of Messina, in her presentation « Contr’un: Simone Weil et Étienne de la Boétie ». Those who want to think, love, and transport purity into political action will be confronted by cutthroats, abandoned by their own, and debased by history. She focused her remarks on the social dilemma of the individual accepting voluntary servitude within the collective through the prism of Weil’s essay, “Méditation sur l’obéissance et la liberté,” which analyzes La Boëtie’s “Discours de la Servitude Voluntaire“ ou “Contr’un.”

La Boëtie’s essential questions are posed without solutions, which leaves perplexing queries open for the reader to resolve. Weil pursues his conundrum with her own query: if in the sciences human beings have learned to harness force and put it to their use instead of being subject to it, why can’t they accomplish the same feat in society? Active complicity in the violence perpetrated by another is a betrayal of natural tendencies, as is the most obvious paradox: why the more numerous can’t hold sway over the few.

Weil illuminates this last concern with the insight that a larger number is actually a weakness; a smaller ensemble can organize and enact a strategy better than can a larger amorphous mass of individuals. History shows that mass uprisings do not endure, for they cannot effectively formulate a method for pursuing a goal. Weil concludes pessimistically that a social order in whatever form is essentially amoral. Nonetheless, to her thinking, remaining aloof in an ivory tower, is not an option, consequently, negotiating with maximum cold lucidity to do the least possible harm and to stay within a certain limit of violence, is a practice that must prevail. This goal requires reaching a spiritual transcendency that goes beyond but through one’s material existence.

Federica Negri

The intriguing contradiction of arriving at transcendency through corporal means is the core of reflections by Federica Negri of the Salesian University Institute of Venice in « L’impersonnel dans l’écriture, l’impersonnel dans la politique. À partir des Cahiers ». Weil’s motivating citation for Negri comes from the Notebooks “To reproach the mystics for loving God with the faculty of sexual love is as if one reproached painters for composing tableaus with colors made of material substances. We do not have anything else with which to love.” [Note: “Reprocher à des mystiques d’aimer Dieu avec la faculté d’amour sexuel, c’est comme si on reprochait à un peintre de faire des tableaux avec de couleurs qui sont composées de substances. Nous n’avons pas d’autres chose avec quoi aimer.” (K9, OC VI 3, p. 170)]

Weil cared always for the materiality of the human being; the sacred in a human being is the whole self, the arms, the eyes, the thoughts: everything. Gravity allows the body to have an experience of the world, for only through one’s physicality is there contact with the real, thus, a body with all its materiality can serve as a lever toward the supernatural. Yet, the true nature of things becomes evident in the process of non-intervention, meaning an abandonment of the inherent moral gravity that drags a being down toward the use of force.

The mystic must never lose sight of the body. For Weil, writing every day was her way to learn, to express, to seize the truth in a physical way. Writing was difficult for her, she used it as a meditation, to make the letters enter into her flesh. By writing down her experiences, she was illuminating the impersonal as the sacred. Entering her thoughts into Notebooks was a conscious study of mystical writing, invariably with the goal of revealing truth. For Weil, this physical exercise was a path of liberty, and even more so of liberation, a process always in evolution. Her entries circling around a profound insight are witnesses to the desire to hide the self in order to bring out the unutterable. Words fail because this ineffable concept needs a mystical language, a new language or perhaps no language at all, to express the superabundance of the divine. Words exhaust the sense of Weil’s encounter with God; truth demands to be shown rather than spoken.

Her prose poem, named “The Prologue,” modestly inserted into the notes of Notebook XI, recounts a mystical experience, impenetrable by the intelligence. This mysterious opus holds two key points of interest: a personal encounter outside the world of the philosopher and an act of grace over which hovers an impression of violence. The knowledge or truth of this encounter is not spoken, but rather transmitted through a series of daily material tasks taken together: speaking, discussing, eating, and drinking. Through it, Weil offers an example of the difficulty in reading or interpreting a phenomenon or interaction; much reflection and thought must occur, for reading the truth of any situation takes extended practice and effort.

Discerning the truth of an experience means confronting the real; her Notebook writing became a witness to her journey. Plato’s meditation on myths revealed to her a way toward truth, particularly when they exemplify the concept that the nothingness of action possesses a virtue. The myth, much loved by Weil, of the sister silently stitching seven feather cloaks to free her spell-bound brothers concerns abstention from speech and training of the body and soul in stillness, orienting traits that embody Simone Weil’s evolving thought.

Negri senses a consistent coherence in the philosopher’s thought and action; for her, writing the Notebooks opened Weil’s body and mind to transcendence, to the impersonal, to a consent to decreation, the sole path to our only true liberty. Weil presents a model for every human being to strive for transcendence through the materiality of the human existence.

* * * *

These three synopses offer a glimpse of the rich ideas shared in the colloquy. Each of the conferees, elaborating on a quote from Simone Weil, offered supporting arguments for confronting modern daily dilemmas, while keeping in mind one’s own teleological purpose and the sacredness of every other being. Resumes of two excellent presentations by Thibaut Rioult and Natalie Calmès-Cardoso given during the 2021 colloquy can be found in issue no 5 of Attention.

Resources

- The full programs of each annual conference are posted on the Association’s website (see here).

- To explore further with a particular scholar through email, address the request to

https://www.simoneweil-association.com/contactez-nous/

- Please urge your university library to subscribe to the Cahiers Simone Weil, an invaluable research tool.

About the Author

E. Jane Doering is a Professor Emerita at the University of Notre Dame and is on Attention’s editorial board. Her published books include:

- When Fiction and Philosophy Meet: A Conversation with Flannery O’Connor and Simone Weil, co-authored with Ruthann Knechel Johansen, Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2019.

- Simone Weil and the Specter of Self-perpetuating Force, Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2010.

- The Christian Platonism of Simone Weil, co-edited with Eric O. Springsted, Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2004.