The Value of “Failed Experiments” in School Studies

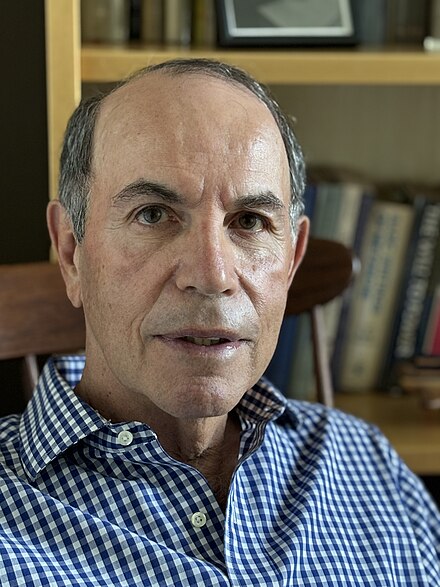

Ronald K.L. CollinsEducation is a practice, but before that it is an idea rooted in an uplifting belief . . . or at least that is the hope. Thus viewed, real knowledge is a sort of liberation from one’s fears and errors, and from the falsehoods to which we once pledged our allegiance, as if falsity and inattentiveness could ever be worthy of devotion. School studies, then, is a path away from the vanity of ignorance and the wrongs committed in its name. It is a path upward.

* * * * * *

She was a master of the essay format. For all the praise heaped on her works, it is well to remember that Simone Weil never wrote a book in her lifetime – what has come down to us is the handiwork of others who compiled her writings under various titles. Among her essays, the 1942 one titled “Reflections on the Good Use of School Studies with a View to a Love of God” is among her best. In 38 paragraphs, Weil covered a wide span of profound ideas ranging from attention and affliction to school studies and manual labor, all glazed with her notion of a “Christian Conception” of spirituality.

What follows is a modest attempt to explore Weil’s understanding of school studies not from a higher “mysterious dimension” but rather from a “secondary” “intrinsic” perspective, one aligned more with what she labels as “the lower plane of the intelligence.” This, to be sure, is not to discount the value of her “spiritual use” perspective, a use of a different order. (see Springsted, pp. 54-55) Even so, ultimately the methodology herein investigated is linked to the spiritual. Moreover, once the notion of humility is brought into the equation, vestiges of the spiritual emerge. Still, that spiritual orientation is more than a few steps up a conceptual ladder better left for another day and a more extended discussion. For now, let us consider how important, though radical, are Weil’s ideas of learning in light of a notion of liberal education worthy of the name.

A method of education: The values of humility and patience

Weil traded educational orthodoxy for a methodology of thinking and beyond. As Weil saw it, the method of education was of greater educational value than robotic-like approaches fixated on memorizing correct answers. In the case of school exercises, a failed attempt to solve a geometry problem, for example, was immensely more important than being told the answer sans any meaningful effort to comprehend the path to a right answer. When it came to pedagogy, process took priority over product; properly understood, the means were more important than the ends in exercising the mind. An aptitude for grasping the truth is what was at stake here.

Genuine education, she posited, requires patience (as in “waiting”); it necessitates a certain availability of thought open to receiving truth. And it also involves the development of a capacity oriented toward “the investigation of a problem” more so than an answer to it. “[I]t matters little,” she emphasized, “whether one succeeds in finding the solution or in grasping the proof, although it is important to have tried to succeed in doing so.” In that respect, there is enormous educational value in trying to track “the origin of each mistake.” Hence, understanding any “failed school exercise” is worthwhile. Ignoring the educational value of such failures is a “temptation [that] must be resisted.” By her measure, “nothing is more necessary for success in studying . . . .” (A passage from her notebooks suggests a link between her notion of education and her conception of doing philosophy: “The proper method of philosophy consists in clearly conceiving the insoluble problems in all their insolubility and then in simply contemplating them, fixedly and tirelessly year after year, with any hope, patiently waiting.” (FLN, 335))

Furthermore, Weil’s conception of education was broad in the sense of not being cabined to any particular subject. Thus, even for “high schoolers,” education meant expanding attention in a way so as “to learn to like all” subjects, from math to French and beyond. Or as she so aptly put it: One must apply “oneself equally to all exercises with the thought that they all serve to develop [one’s] attention . . . .” Improving one’s attention (again, properly understood) was key as was her related notion of reading (see (Levy & Barabas, 143-149).

And then there is “the virtue of humility,” by which Weil means the “contemplation of one’s own stupidity.” This Socratic virtue, if you will, is “a treasure infinitely more precious than any academic progress . . . .” Education, thus viewed, leads to knowledge of one’s ignorance, which in turn can prompt humility – a virtue incompatible with an arrogance born of out of ignorance.

This cultivation, both at a lower level and at the spiritual plane, should be the mission of education. Thus, it shuns indoctrination and memorization. So too, it is neither mass nor standardized. Unlike much institutional education, it is not dictated by the demands of the collective. A “student’s interpretation of the world” comes, after all, from “what is in the air” around them, from the domain of the Great Beast. (Bloom, 124) In that regard let us not forget what Weil said on this general matter in a 1943 report for the Free French: “Any kind of collectivity, institution or collective way of life [is in need of] reform or removal.” (Levy & Barabas, 10) Moreover, such cultivation might be said to involve “a training in boldness: it demands from us the complete break with the noise, the rush, the thoughtlessness, the cheapness of the Vanity Fair of the intellectuals as well of their enemies.” (Strauss, 8).

Cultivation of this order is not a routine for the docile but rather a process for those energized to engage with learning. It is not any kind of “muscular effort” or a hardship that must be endured. Hardly! It involves a certain “joy of learning,” which is as “essential [for students] as breathing is for runners.”

In all of these ways, and yet others, Weil’s pedagogical approach was at war with most institutional educational norms both in her times and ours. But how and why?

Weilian education vs modern mass education

In her classes and writings, Simone Weil did not believe in teaching to the exam; she shunned the prescribed textbooks; and she cared little about grades as ends in themselves. Her words: “It is therefore necessary to study without any desire to get good grades, pass exams, or obtain some academic outcome, without any regard for . . . natural aptitudes . . . .” Not surprisingly, “of Weil’s fifteen students [at LePuy], seven were presented for examinations, but only two passed.” (von der Ruhr, 8). Much the same happened when she taught at Auxerre. (Pétrement, 169-170 and Rozelle-Stone, 13)

Weil’s pedagogy was the antithesis of modern education, which is mostly mass, standardized, compartmentalized, computerized, and often parochialized. Google word searches have replaced the use of libraries and books; balkanized information is cut and pasted into students’ minds. The automatic AI acquisition of data has largely derailed traditional notions of liberal education. “[T]he posture of the intelligence,” as Weil conceived it, bends ever more to the electronic product of artificial intelligence. Education in great books is being replaced by schooling in information technologies. Grade inflation yields to the demands of the educational marketplace. In colleges and graduate schools, publication credentials are often more important than teaching skills.

However much we admire Weil’s illuminating pedagogical approach, let us not speak falsely.

To be sure, the kind of education Weil envisioned in her “School Studies” essay is so radical and contrary to modern norms of education as to be summarily dismissed in most schools (save perhaps the likes of St. John’s College). Would any public school ever hire such a teacher? Would even a Christian one do so? Would the faculty of any educational institution tolerate such education? And would the parents of high school students countenance such approaches to education? Moreover, we live in times when it takes so little to offend so many in ways that disrupt the educational process. Meanwhile, classics departments struggle to stay alive since they lack the kind of “utility” demanded in a modern commercialized world.

How to begin to teach in a Weilian way?

Where, then, does this leave those sympathetic to Weil’s views? How does one begin the process even at the “secondary” plane of the brand of learning discussed above? What is the way? What are the texts? What about exams and grading? What to do about the technologies of education? And what about the problem of mass education? (Questions: Is Weil’s geometry example of education applicable in the same way to liberal studies subjects? Or to studying the Iliad or Plato’s Republic or Marx’s Das Kapital?)

By way of a preliminary and therefore incomplete reply, let us think again about the matter of method. Recall that Weil’s method is not muscular; in “itself it does not involve tiredness”; and it is not synonymous with willpower. It is, however, patient; it is joyous and therefore “untiring”; and it requires a certain suspension of one’s thinking so as to leave one ready to receive truth. To get some sense of this method in practice, consider

the example of a geometry teacher who, in working a problem for the benefit of the student, presumably already knows the solution to the problem and has already worked this very problem several times for the benefit of other students. In order to exemplify the method of waiting upon truth, the teacher must in a sense forget the solution — or rather, the teacher must remember the problem, must shift his or her attention to the problem as such, perhaps by asking: What makes this “problem” a problem? (Nelson, 85)

Viewed from this educational perch, consideration of why certain questions themselves raise a problem is antecedent to any pocketing of right answers. By this measure, “the teacher will also presumably realize that a problem is simply not the kind of thing that can exist in the abstract. Every problem worth the name is a problem for someone.” (Ibid.)

“Why are you stumbling in your attempt to answer this question?,” a teacher might ask. What is the impediment? What is blocking the student’s mind?

Accordingly, the teacher is also therewith compelled to ask the student: What makes this a problem for you? And here the situation comes full circle, as the teacher is really asking the student: What is your problem? This is how the method is made known. (Ibid.)

This “your problem” approach points, of course, in multiple pedagogical, ethical, and spiritual directions. In the process, the mind opens and intuition of a higher order awaits students. At the very least, this “secondary” or lower-level approach invites students (of all ages) to confront the mistakes in their thinking and how they approach a problem, be it in geometry or the uses of language. It counsels them how even “failed experiments” can set them on “the right track” and can be a bridge to truth.

Such an approach to school studies, while in need of greater elaboration and short of Weil’s ideal, might nonetheless be a way to begin to think about how to reform education in more realistic respects while vigilantly sensitive to the higher truths Simone Weil equated with “a love of God.”

Bio Statement

Ronald Collins is the editor of Attention and co-editor, with Eric Springsted, of A Declaration of Duties toward Humankind: A Critical Companion to Simone Weil’s The Need for Roots (Carolina Academic Press, 2024).

Sources

Simone Weil, Basic Writings, ed. & trans. by D.K. Levy & Marina Barabas (New York: Routledge, 2024) (the translated quotes used in the text above re Weil’s “Reflections” essay are taken from this book).

Allan Bloom, “The Crisis of Liberal Education,” in Robert A. Goldwin, ed., Higher Education and Modern Democracy(Chicago: Rand McNally & Co., 1967), pp. 121-139.

Christopher A.P. Nelson, “‘To Make Known This Method’: Simone Weil and the Business of Institutional Education,” in A. Rebecca Rozelle-Stone & Lucian Stone, eds., The Relevance of The Radical: Simone Weil 100 Years Later (London: Continuum, 2010), pp. 76-90.

Simone Pétrement, Simone Weil: A Life (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976, Raymond Rosenthal trans.).

Mario von der Ruhr, Simone Weil: An Apprenticeship in Attention (London: Continuum, 2006).

Eric O. Springsted, Simone Weil for the Twenty-First Century (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2021).

Rebecca Rozelle-Stone, Simone Weil: A Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024).

Leo Strauss, Liberalism: Ancient and Modern (New York: Basic Books, 1968).

Simone Weil, First and Last Notebooks. Trans. Richard Rees. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970)

Recommend