From Italy — Liliana Cavani’s Cinema of Fraternitas: An interview about her never-produced movie on the life of Simone Weil

Michela DianettiLiliana Cavani is one of the most influential and critically lauded Italian filmmakers of her generation. In August 2023, at the age of 90, she received the Golden Lion for Career Achievement at the 80th Venice Film Festival to mark the significance of her long and outstanding filmmaking journey. ‘In her work, Cavani intertwines philosophical, political and spiritual musings (a trait that resonates with Weil’s work, which started to make waves in Rome in the 1960s). Her esteem for Weil is most evident from her proposed biopic of Weil, for which a script was co-written with Italo Moscati. As fate had it, however, the film never made it to production.

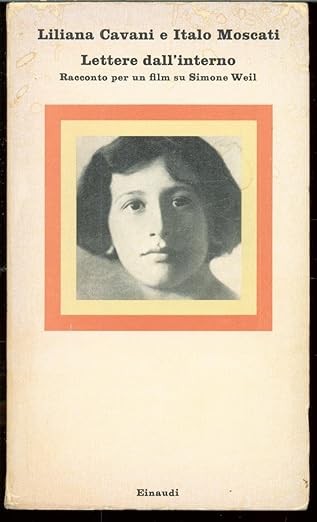

In the 1974 volume titled Lettere dall’interno. Racconto per un film su Simone Weil (Letters from the Inside. A Story for a Movie on Simone Weil), the publishing house Einaudi released Cavani and Moscati’s script in the series “Nuovi coralli.” The same year another one of her movies, also in collaboration with Moscati, was released in Italian cinemas. This movie, Milarepa, is similarly a biographical movie about the life of an extraordinary individual, as was her 1996 TV movie about the life of Francis of Assisi (and her other adaptations of 1989 and 2014). It is unsurprising to find the name of Simone Weil alongside that of St. Francis and Milarepa as it suggests a common thread in Cavani’s career – a focus on figures characterized by a “lived philosophy” (figures, such as Elsa Morante’s ‘Felici-Pochi’ (Happy-Few), amongst whom the Roman writer includes Weil as an image of “the intelligence of saintliness”).

What follows is a series of questions presented to Ms. Cavani this past August by Michela Dianetti. Ms. Cavani’s replies were translated from Italian by Ms. Dianetti. This exchange came against the backdrop of the 80th anniversary of Weil’s death, and also Cavani’s latest production, L’ordine del tempo, released in Italian cinemas on August 31st.

# # # #

- Dianetti: The idea of a “missed” movie about Simone Weil can only cause regret. What led you to abandon the project and continue instead with the making of the movie on Milarepa?

Cavani: I couldn’t find a producer interested in the Weil project. It was around for some time but with no luck. Fortunately, I had the chance to make a movie that in the meantime had become possible: The Night Porter. This movie was very successful and as a result, I was able immediately after to realize another project that I had for a long time: Milarepa. I made that movie, which was very important to me, with the same production of The Night Porter: the “Lotarf film.” At that time, I learned that they were going to make a movie about Simone Weil in France. Maybe they did but in Italy, it was never screened.

- Dianetti: In your Weil book, you and Moscati warn that the movie was meant to be made in 1971. On the back cover you talk about it as “the most urgent movie to do” in order to understand the ideological crisis of those years, and you talk about “arretratezza dei colti” (the backwardness of the educated). What was the gestation of the proposed movie? Where did the idea, not to say necessity, come from, and how would you describe the primary objective of making a movie about Simone Weil?

Cavani: Unfortunately, making movies is not like writing books; there is a significant economic aspect in the production, even if they are not colossal films. Rai (the national public broadcasting company of Italy) participated in the movie Milarepa but not in the one about Simone Weil. I was told that only a few people knew her. Milarepa was unknown in Italy and those who knew him were very few, but strangely and fortunately the executive at Rai had heard about Milarepa and had read the book about his life.

The fact is that dealing with Simone Weil means dealing with cultural and social issues that are still very important today. I never knew whether the Simone Weil project was carried out in France. Curiously, in the penultimate exhibition of the Venice Biennale two years ago, an artist, if I remember correctly from Sweden, exhibited the book we published on Simone Weil as a work of art. In its own way, I interpreted it as “the dream of a movie to be made.” Who knows if it will ever come true?

- Dianetti: Can you tell us something about the title of the volume Lettere dall’interno?

Cavani: The title is a poetic image, I think. With Simone Weil we walk an untrodden path that is uncommon . . . it is from elsewhere.

- Dianetti: Before, I mentioned Elsa Morante. The Roman writer’s passion for Milarepa is well known, not to mention for Weil. What role did Morante play in writing the movie about Milarepa and the screenplay about Weil?

Cavani: I had a rare acquaintance with Elsa Morante. I happened to meet her at her house with Pier Paolo Pasoliniwhen she was thinking about the music for one of his movies. Another time I happened to come to the restaurant where she usually went and she nodded to me to sit at her table. And then we would talk about cinema, of course. She liked Milarepa, she had suggested it to me as something to read, and I must say that it was a nourishing read.

- Dianetti: What attracted you to the work of Simone Weil? And what, in your opinion, is the greatest difficulty in recounting her life and thought?

Cavani: I read several of her books. I was interested in her political vision, the ideal socialism that somehow has its roots in the Franciscan Fraternitas. Not surprisingly, at the center of the French Revolution, there was Fraternity. I made three movies about Francis of Assisi. Simone Weil went to Assisi. I think she rightly recognized herself as a sister. She lived not too differently from Francis. Fraternitas for them was a serious matter: they believed it to be the key to reading Creation . . . and only by looking at the world in this way might we save ourselves from childish contemporary political visions.

- Dianetti: In the script, in the scene in which Weil decides to work in the factory, she is accused of hypocrisy and sentimentality, and of falling into the dynamics of the “king of coal” who one day descends among the workers and then returns to the comfort of his castle. In your opinion, is it truly possible to put oneself into the shoes of the worker as Weil did? Or does the fact that Weil didn’t have to go to work but was there out of choice somehow make her perspective biased?

Cavani: Hard to say with clarity. Years ago I made a documentary on the Poor Clares. When they changed their lives for the choices they made, they were prepared to change the way they dressed and ate, basically to change their whole lives. Simone Weil lived as the pioneer of a possible way of being, as a lay nun of a possible vision: hers. She lived according to the rules of her very personal convent. She chose a life in which she did not feel uncomfortable, feeling “sister’ to many people and, at that time in the factory, to the workers. And I believe that after that experience she always dressed with great simplicity. Fraternitas means sharing.

- Dianetti: In the book you and Moscati write: “The script presents a young woman trying to match ideas with action. Reality is pressing and every effort must be made to understand it without dreaming.” This is a movie that represents an extraordinary life lived “from the Inside” of the evils of her time (the ‘30s and early ‘40s). Even so, it could still speak to an audience of the ‘70s. If you were to think of proposing it for television as a movie for today, I wonder if it would still be able to resonate with a modern audience in a technologically transformed world. What do you think? Do you think yesterday’s dreams are different from today’s?

Cavani: I think dreams are always the same. Technology has changed so many things in our lives, but it hasn’t changed our “loneliness” despite so much progress. Sharing, Fraternitas is the only project that concerns our possible happiness. The other achievements, many very useful, have united us more, but only by insisting more on the vision and culture of the value of Fraternitas can we speak of progress. Scientific progress, though often very useful, does not always have connections with the development of the Fraternitas. Indeed, it often has repercussions such as terrifying weapons, which the current culture must further recognize as the inhumane and unacceptable work of fools and thugs.

- Dianetti: In the script, you emphasize the importance of the fundamental Weilian idea of the “uprooting” of culture. This is particularly evident when you present the phase of Weil’s life in which she decides to work in a factory and shares the workers’ suffering. In her diary, now contained in Oppression and Liberty, Weil notes how the pain of daily labor did not ignite in the workers the will to revolt, as Marx had suggested, but led them to docility. This slow and inexorable descent of the human being into the state of “things” — and therefore their inability to think about their condition, or to think in general — is a central point in your script. In my opinion, it is masterfully represented in the script the configuration of a society focused on power and social oppression and the lack of equal access to education (for Weil, in fact, the real revolution would be that focus on equal access). At the same time, in the script, the representation of this condition is balanced by moments of extreme beauty. For example, there are those instances in which Weil abandons herself to fatigue and sees for a moment another a different reality, one in which workers, dressed in elegant clothes, take orchestral instruments in hand and play Mozart. In this altered reality there is a beacon of truth that makes the (un)reality of the factory seem distant and impossible. What do you think about Weil’s idea that being rooted in beauty is a human need? Is there room for beauty in today’s system of education?

Cavani: There is always a place for beauty. Especially as we are increasingly immersed in advertising market propaganda. Given this, more cultural education and suitable schooling could help a lot. Simone Weil, when she decided to work in a factory, understood that this was the true and only step to take: to be together and to understand what the human being actually is. She did, without knowing it, what Francis of Assisi did. He participated in a violent war and was in prison in the midst of violence, and he asked himself: is this the fate of humans? After leaving prison he started from scratch: what is the way? He put in his head that the way for all is in PEACE and that everything is Fraternitas: Il cantico delle creature (the canticle of the creatures) is also a scientific text: all creation is made of the same matter, we are brothers so why do we kill each other?

- Dianetti: Again on power and education: I really liked the scene that would have opened the film, in which Weil, as a teacher, dictates to a student a sentence about power to write on the blackboard. The student writes a sentence but without really knowing what he wrote, and Weil presents the example to the class: “he has simply lent his hand and his technique. He has absorbed an idea, he has not sought it. It can be a good idea. It can be a bad idea. How many other misconceptions, preconceptions, and clichés, do we absorb under dictation or breathe in the air?” (L. Cavani and I. Moscati, Lettere dall’interno, Einaudi, 1974). In the 1930s when Weil was teaching it was a time of totalitarianism. What do you think of our own time and the often extreme ideas floating in the air today? How can we begin to be attentive, in a Weilian sense, given our current situation?

Cavani: To answer, I repeat what I said above. You see, Dante talks about Francis in The Divine Comedy, dedicating almost an entire song to him (if I am not mistaken the 17th). Some people have found an answer to our fundamental questions, among them, I choose Dante and Francesco. I think culture can do a lot to prevent the triumph of Stupidity and Arrogance. The concept of Fraternitas should be the basic concept of every approach because only by following it can we prevent the development of the criminal technique of weaponizing life. It is from the Fraternitas that we can begin to understand that we become the “enemies” when we let ourselves be guided by arrogance and vanity. Unfortunately, the latter are the weapons of stupidity that too often govern our world.

- Dianetti: To conclude, you and Moscati talk, and rightly so, about “a movie that could and can still be made.” So, finally, I ask you: would you make this movie today?

Cavani: I don’t think I will return to projects of the past because of an inner law that pushes me elsewhere. I have finished my latest movie L’ordine del tempo, inspired by my reading of a book by the physicist Carlo Rovelli. In this movie, I talk about the meanings of life.

Dianetti: Movies like those about Milarepa, Saint Francis, and Simone Weil, allude to the spirit of Fraternitas, to that altruism from which a certain type of art, always political and always current (like that of Cavani) originates. Unfortunately, while we have not had the opportunity to see a movie on the life of Simone Weil realized by Liliana Cavani, at least we are fortunate enough to see the evolution of her artistry continuing with L’ordine del tempo.

Ms. Dianetti is the Italy correspondent for Attention.

# # # #

7 Recommendations