Weilian Lessons from Abroad: Michela Dianetti’s Interview with Gabriella Fiori

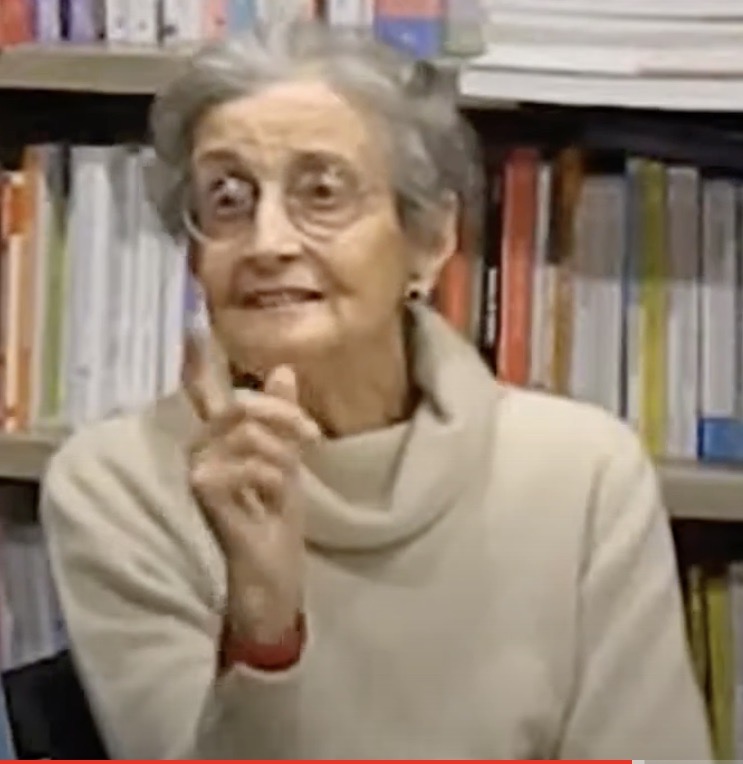

Michela Dianetti & Gabriella FioriGabriella Fiori was born in Florence, Italy on March 15, 1930. She has degrees in modern literature from Cambridge University and Université Grenoble and has long specialized in English and French studies. She has taught in secondary schools and at Queen’s University in Belfast. She is a translator in the field of non-fiction, fiction, and poetry and is the author of numerous books and articles. The interview with Ms. Fiori follows the list of works listed below.

A sampling of published works (Italian & English)

Fiori is the author of 38 works in 122 publications, six languages, and 1,208 library holdings. Her works include:

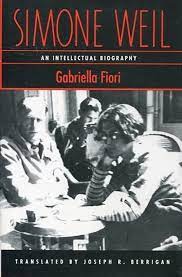

- Simone Weil : biografia di un pensiero. Milano, Garzanti, 1981Editions: 1981, 1990, 1997 [reprint of 1990 ed.], 2006

- Simone Weil: An Intellectual Biography (U.S. ed., 1989).

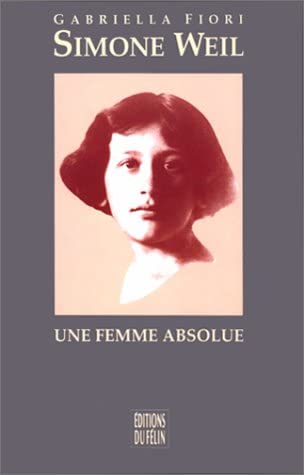

- Simone Weil : une femme absolue Paris, Éditions du Félin, 1987, written and published originally in French. Two French editions: 1987 and 1993

- Simone Weil: una donna assoluta. Milano, La Tartaruga, 1991, written in Italian by the author. Two Italian editions: 1991 and 2009 Japanese edition 1994, Spanish (Argentina) edition: Simone Weil: una mujer absoluta. Buenos Aires, A. Hidalgo, 2006, Polish edition: Simone Weil: kobieta absolutna. Poznań: “W drodze”, 2008

- Anna Maria Ortese, o, dell’indipendenza poetica, Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2002.

- Coauthored with Mariolina Graziosi and Adriano Marchetti, Simone Weil : poesia e impegno, Milano, Unicopli, 2003

- Introduction to Armida Pezzini, Pensare la soglia : la riflessione di Simone Weil tra filosofia e mistica, Siena, Cantagalli, 2007.

- “Simone Weil o dell’esperienza dell’autoesilio,” Testimonianze. vol. 50., no 1 (2019)

- “Realism and Faith in Transformation Through the Creativeness of a Conscious Life: Simone Weil (1909–1943),”Analecta Husserliana, vol. 60 (1999).

- “Marie-Magdeleine Davy, una solitaria dell’Assoluto,” Testimonianze, issue 477, no. 3 (2011), pp. 99-116.

- “Simone Weil : le langage d’une écriture,” Recherches sur la philosophie et le langage, no. 13 (1991), pp 119-125.

- “Albert Camus et simone weil une amitié sub specie aeternitatis,” Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 29, no. 2 (2006), pp 128-139.

- “Elsa Morante, lectrice des Cahiers de Simone Weil,” Cahiers Simone Weil, vol. 32, no. 1 (2009), pp. 65-96.

- “Storia di un’amicizia”, in R. Fulco e T. Greco, L’Europa di Simone Weil, Quodlibet, 2019, pp. 213-228.

Related

- Libreria Gioberti — Gabriella Fiori in conversazione con Antonella Lumini (Jan. 26, 2017 — YouTube)

The Interview

What follows is a series of questions e-mailed to Gabriella Fiori in 2022 and early 2023 by Michela Dianetti along with Ms. Fiori’s replies (all translated from Italian by Andrew Florio and Michela Dianetti). Thanks to Ms. Fiori’s daughter, Stefania Andreini, who kindly assisted in bringing this interview to completion. Unless otherwise noted, all of the following questions were posed by Ms. Dianetti. – rklc.

Michela Dianetti: Let me begin by saying how honored I am to have this opportunity. Your works have been very important to me since the very first day of my college education when I discovered Simone Weil.

You have had an incredible intellectual life, and you have been one of the most influential scholars in the Italian Weilian community.

Biography of Weil

Question 1: Your biography of Weil came after two other monumental ones, first by Jacques Cabaud’s and then by Simone Pétrement. What was your objective in writing a new biography?

Fiori: My objective became obvious with time. I always enjoyed writing, as I do reading, women’s books, alone or together with my mother who was a lover of France and who taught me French when I was six. I wanted to understand a woman who, through her life, in a particularly dramatic period of our human history was not properly a writer but a thinker. She was also an idealist who experienced the most significant tragedy of her time and tried to understand and resolve it. She did so by grounding her thoughts and actions in history but in her own unique way, and with a genius’ intuition and a woman’s tenderness.

I wanted to show her in her whole being, with her peculiar personality of a young woman, and to recount her experiences that let her be an earthly creature among us. Precisely, as if she was with us now.

My mother brought me to Paris (a city she had visited in her youth) when I was 19 years old. Some years later, in 1970-71, I began to think about writing something on Simone Weil (perhaps an introduction and comment on her written works). It was after an early informal conference on Weil (around June of 1972) that the idea of a biography emerged. Years of fascinating encounters ensued, usually in the summertime, autumn, or Easter holidays as I taught English in middle schools. Meanwhile, in letters, I write about Simone Weil with a French friend, Hélène Vetch — we met in 1953 at Oxford’s Wadham College, where I was taking a course in English literature from the British Council.

Question 2: You wrote that your work was based “solely on evidence provided by people who knew her and upon her works.” And an impressive lineup it was, including André Weil, Father Perrin, and Simone Petrément, among others. What can you tell us about how that came to pass? Tell us about your work with these three individuals.

Encountering André Weil

Fiori: I thought that only real-life testimonies, from friends or detractors, could give me answers, given that everything in Simone Weil relates to her everyday life — that is, her anguish and her impatient will to know.

My first meetings with André Weil took place in 1976. I did not have the courage to go and meet him; the idea of it made me uneasy. “He is tough” they told me. A cousin of theirs (Raymonde Nathan) encouraged me a lot. She had been left motherless and had spent her childhood and adolescence with the Weils and really loved the two siblings. She told me: “Go, go, with people like you, André will never be tough, you’ll be fine.” So I went to meet him in the house at Rue Auguste Comte, which overlooked the Gardens of Luxembourg. I could make out the trees from the French window. André sat at a long table, open in front of him was a Russian book. He was a fascinating man; his face exemplified intelligence. On the wall to the right was a small closed bookcase, with two shelves containing all of Simone’s books and papers. Our conversation lasted a good hour, but he barely spoke, he asked me lots of questions. Between one question and the next, he patiently awaited my response. I was very intimidated. I kept giving answers and they were listened to respectfully. After leaving I was moved and dazed. I did not know how it had gone, which is what I said to a friend who asked for an update.

I came to know him only a year later when I returned to Paris and telephoned him. He answered cheerfully: “Ah, you’re back!” and immediately invited me over to see him. The next time over a year later, I rang him again to say I had come back to Paris and he answered affectionately like an old friend: “I’m back, oh great!” He quickly invited me over for breakfast at their house; since then I have often gone to see them and also been their guest in the countryside.

André was curious about everything, childlike in fact, and the intelligence, that great intelligence, made him beautiful. When he came to have lunch at my home in Florence with his wife Eveline, the first thing he did was tour the garden that contained a towering 100-year-old Magnolia. He wanted to understand everything. He questioned me endlessly about my life and my family. I was struck by how intently he listened to the words of my youngest daughter, who was only little then, about 12. To get to my house he came down from the Abbey of San Miniato al Monte, where he had gone to a concert. Another time we visited the Benedictine monastery in Rosano, where the nuns still practice liturgy in Latin. He kept his eyes shut throughout the entire mass; I felt like he wanted to get closer to Simone. We traveled there in my Fiat 500: to this day I don’t know how all five of us managed to fit in that tiny car.

We visited a community of monks as well, in Gricigliano, where at the time there were the Benedictines of Fontgombault. It was a gorgeous day with clear and sunny blue skies. André and I walked around the walls of the convent stepping on the dry leaves which crunched under our feet. And André said to me:

“My sister wanted to change the world, but the world doesn’t change, you have to endure it. There are two options, you either kill yourself or adapt to the world.”

I was also their guest in a small house they had rented near Paris. There was a small garden with boxwood hedges and we were always there, or taking walks in the woods nearby. At the time (it was 1988) my biography was always a topic of conversation between us and he would ask about the different chapters.

André was very close to his wife Eveline, a calm and easy-going woman. He was always at her side. Eveline died suddenly, far too early. André told me it was worth going to Paris to talk with me because he really trusted what I said, a sentiment that I felt was real. I remember speaking at the FNAC along with a couple of other academics and he was in the audience. My second book on Simone had just been published; it first came out in France in 1987 and then in Italian four years later. He read it soon thereafter and enjoyed it very much, which honored me considerably. He invited me along with another scholar to a department store for lunch. I was so thrilled with all of that! It turned out to be the last time we would see each other in person.

Padre Perrin

Father Perrin was practically blind. Yet from an upper floor of the convent in Aix-en-Provence, he hopped down the grand stairs quickly like a little mouse, all the while holding onto the marble banisters. In his study, I noticed a black four-poster bed. A black drape depicting a large red setting sun sinking into the sea hung at the headboard. With cheerful efficiency (a quality of his that struck me the most), he swiftly arranged all the meetings I was hoped for: First, there was a day with Gustave Thibon, his friend, (together they wrote Simone Weil telle que nous l’avons connue).

Then there was a meeting with Jean Ballard, founder and director of the fine magazine Cahiers du Sud, for which Weil wrote glorious articles. There, she was honored and listened to, but always debating. The meetings took place in an attic where she sat at the end of a long sofa. I met Marcelle Ballard, Jean’s lovely wife, whom I saw again after his death. She spoke of a very sweet Simone, bent over the cot of her newborn in 1942. The collaboration with Cahiers du Sud allowed Simone to become more noticed.

Padre Perrin spoke to me fervently. Though he was practically blind, you really couldn’t tell it since he was more active than those of us who can see. His organizational and pragmatic spirit struck me. He told me many things. He wasn’t at all affected or pathetic, it wasn’t in his nature. A very intelligent man.

Simone Pétrement

Around 1974, I went to see Simone Pétrement at Enghien-les-Bains. She had been a friend of Simone Weil’s at the Lycée Henri IV, and subsequently at la Normale. That continued later in Simone’s life when the Weil family was evacuated to the mountains above Marseille. She had such a dedication to the biography; it was one grounded in a life commitment to a deep friendship.

Pétrement did her job with a great deal of responsibility and seriousness — according to her editor, she was also difficult to please. She lived in an old house, a little villa with a garden. She found it hard to speak of her work. She had carried out an important task and kept a promise made to Weil’s parents. Now, she seemed exhausted.

In pictures from her childhood, I saw her fresh-faced and sweet. In her, there was an expression suggesting an effervescent intelligence, yet at that moment she found it difficult to even serve tea. I had the impression of a suffering woman who needed tranquillity (she wasn’t even that old, born in 1907). Her severe housekeeper stared me down, fearing I would tire her out; she couldn’t wait until I left. I remember her unhappiness which was made clear to me by words exchanged on the wooden stairs leading up to the upper floor. Truthfully, the visit was somewhat melancholic. Pétrement, however, was pleased to have carried out her task; she kept her promise to write about a great friend. Her work is absolutely reliable, credible, and influential. She described Weil’s youth and her schooling so well. (Something of the same could be said of Gilbert Kahn, for he too was a friend and classmate of Simone’s. He was a little younger (born in 1912). He, too, proved to be an important Weil scholar. His impression was that, even though Pétrement had personally known Weil and wrote an excellent biography, the way I described her (without having known her) was more vivid.

Question 3: In the recently published Appendix of L’Europa di Simone Weil, titled Storia di un’amicizia, you speak of a “Weilian fire” in the 1950s “around the writer Cristina Campo, together with the psychoanalyst-writer-artist Gianfranco Draghi, the poet Mario Luzi, who have all since died, and the essayist Margherita Pieracci Harwell.” Could you tell us a bit more about this Italian community of Weilians? Did you ever get in touch with them?

Cristina Campo

Fiori: Not only were we acquaintances, but we all became more or less friends over time except for Cristina Campo, however. I only read her work since every time we tried to meet fate got in the way. A mutual friend, Marcella Amadio (also a child of musicians like Cristina), let me know of Campo’s desire to meet me personally, but it wasn’t possible. It’s better that way really: I am happier to have gotten to know her through the essence of her original and profound writings. Since some have described her as giving a “cutting” criticism, I really wouldn’t have liked that.

Cristina Campo was among the earliest intellectuals to recognize the value of Simone Weil and how important she was in our time. She was right in translating Weil’s Venise Sauvée for the first time (where the city is saved by its beauty and Jaffier is the conspirator who sacrifices himself by abandoning his friends to be the means of salvation). This story is an example for all of us in the face of the hardships of our time. In this regard, I refer here to one of Weil’s aims: individual universalism. To realize you are an instrument and to be conscious of it in every action, thought, and feeling of your existence: Venice Saved is a great example of this. Venice is saved by itself and Jaffier knows he is simply an instrument in the fulfillment of its salvation. Such Weilian universalism is derived from Europeanism.

Campo also helps us to better understand Weil’s spirituality, even if Campo is too rigid and demanding when it comes to Weil’s catholic culture (or lack of culture) — such things that, according to her, prevented her from getting completely involved with the church, its liturgy, and with baptism. When Campo criticized Weil for ignoring basic elementary notions of theology and asceticism, she forgot that Simone Weil, up until her conversations with Father Perrin, had largely completed her education alone. She was taught by her parents and brother the most complete form of agnosticism with the only exceptions of her meetings with the daughter of Jacques Copeau, Hedwig (later soeur François) whom I met as a Benedictine nun in a community near Paris.

Gianfranco Draghi

I also had helpful meetings with Gianfranco Draghi, a committed Europeanist. I had healing conversations with him along with other people whom I hold dear such as Rita Biancalani and Leonello Rabatti. (Biancalani, was friend-cum-student in the course titled “Female Writing as a Road to Women’s Identity.” I started that course and it lasted 20 years, from 1989 to 2009.)

I had already met Draghi a couple of years earlier, perhaps before my biography of Weil came out (18 June 1981). He had held conferences in Florence on the idea of Europe, conferences which my mother used to attend. The time I sought him out he was living in Settignano. I was told he had taken an interest in Weil and that he was a member of the Cristina Campo circle — he was also a friend and admirer of hers. Back then he was different from who he became in the 1990s. He was refined, from a distinguished family (he used to greet me with a slight bow). Always quite composed, he had become the most famous psychoanalyst in Florence. He was rather cheerful and that cheerfulness was contagious to his guests at dinner parties. Though he had written Ragioni di una forza in Simone Weil (Caltanissetta, Salvatore Sciascia, 1958), neither then when I knew him nor now do I remember any reference at all to Simone Weil during our conversations. It’s odd: when Rita Biancalani, Leonello Rabatti, and I were at his house, Simone Weil seemed present, breathing alongside us. Gianfranco Draghi died in 2014 when he was 90. His friend, the abbot of San Miniato al Monte, accompanied me to his funeral in a small church above Fiesole.

Mario Luzi

Draghi and Mario Luzi had discussed at length which one of them was the first to introduce Cristina Campo to La Pesanteur et la Grâce, which had just been released and enthusiastically read in Paris in 1947. We don’t know and we never knew which one of them it was. In that book, Campo recognized (and she was the first to do it in Italy) an educated inspiration for the life of the spirit in Weil. In a conference in Florence (25 March 2017), the minutes of which were released in December 2021, one scholar called Campo “un classico dello spirito” (a classic of the spirit).

Mario Luzi loved my biography. Every time there was some event about Weil (the last time was at a conference at the Centro Coscienza di Milano, in 1993) we would run into one other. Once, at a conference where I brought my biography with me to give him, he literally ripped it from my hands, so impatient was he to read it. Given my research on Weil, he wanted most of all to present me to the University of Belfast. (I later taught a course in Italian studies in 1987.)

Margherita Pierarcci Harwell

Margherita Pieracci Harwell was married to Dwight Harwell, who died too early, and was the American secretary of Selma Weil, Simone’s mother. Margherita achieved something that Campo had always wanted, but couldn’t as she felt uneasy with long journeys: meeting Selma Weil. Thanks to Selma Weil, she met her husband. I saw the pictures of their wedding, which took place in the Weil household. Seeing those pictures gave me joy and made me quite emotional.

I came to know Margherita in 1974 at a conference on Simone Weil held in Cerisy-la-Salle in Normandy (at the time in Cerisy there used to be conventions lasting 10 days, the “décades”). It was organized by the Association pour l’Étude de la pensée de Simone Weil and was packed with information and appearances by scholars aware of Weil’s importance. Cerisy was a suitable backdrop for the meeting. It was the third colloque, following a second one that took place at Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre (near Paris) in 1972, after which l’Association was founded. Margherita’s main talent as an essayist was her balance in both style and opinion.

Question 4: Recently, I read your article published in French in Cahiers Simone Weil. Could you say more about where your interest for Elsa Morante’s interpretation of Weil stemmed from? You also mentioned a conversation you had with her. Please tell us when that was and the circumstances surrounding that exchange.

Fiori: My desire to understand the reasons behind Elsa Morante’s interest in Simone Weil gradually grew the more I got to know her work. I met her nephew, who told me that despite Elsa’s changeable temper (one day adoring, the next hypercritical to all), she always held Weil in very high regard and always loved her with dedicated admiration. She always kept the Weil’s notebooks close to her.

When my biography came out, she would happily gift it to people (so an actor friend of hers told me). She would say: “We should be as Simone wanted it; but it’s not possible.” I telephoned her to tell her of a conference on Weil organized by l’Association pour l’Étude de la pensée de Simone Weil, which takes place every year. She told me she wouldn’t go. She had an aloof tone, not a single bit of enthusiasm and I don’t remember any mention of my book. I couldn’t understand why she would have such an attitude and it caught me by surprise.

I don’t remember exactly when this phone call happened, maybe in the early ‘80s.

I think it was amazement that piqued my interest in Morante’s literature as I found her so different in comparison to Weil. Not even her nephew (who told me about his aunt’s loyalty to Simone) could understand the reason behind her love of Weil. Elsa Morante was difficult in picking people to love. But Morante’s love of Weil lasted throughout her whole life. Eventually, I came to understand that. The short poem Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini, where Simone appears as one of the “felici pochi,” revealed that love.

Iris Murdoch

Question 5: You translated seven of Iris Murdoch’s novels and your relationship with her was that of a friend. I really appreciate your definition of Murdoch as a “philosopher-novelist to reckon with,” “a furtherer of Weil’s work.” In Murdoch’s private library in Kingston, I found your book Une Femme Absolue, with this dedication: “So often remembering our good time together, through her books. With Simone Weil, beyond time and space, friendly”.

Could you tell us something about your first meeting with Murdoch? Where and when did it take place and what the circumstances were? And could you tell us more about your conversations on Weil?

Fiori: The first time I met her was at my house when I invited her over for lunch with her husband John Bayley. I remember how she came in: ladylike, reserved, wearing a blue suit. She was affectionate and gave me an impression of generosity. At the time, I was translating The Nice and the Good. The first question she asked (as she sat right beside me, to my left, at my oval table) was regarding myself: “When will you write something of your own?” That really struck me. She liked my daughter Stefania’s eyes and said “Wonderful eyes.” My brother also sat at the table and took a shine to both Iris and John.

She was never invasive nor did she come across as authoritarian in coming into my home where she was the star of the day. There was a trustful confidence about her and a certain humility. A dear friend of mine, Grazia Livi, a journalist and writer, also came along to my place to interview her. In 1975, in England, I went to visit her. I remember a grassy hill; her beautiful house was at the top and it seemed to me like it had been put there by fairies. With me was a Weilian friend with whom I was doing research. Inside, I remember a large hall, veiled by the dim light. Her welcome was gracious and simple. Later, I wrote to tell her I would continue my research on Julian of Norwich’s biography, and she approved. “Una donna libera che lasciava liberi” (a free woman who set the others free), she said.

The Italian & English Language Receptions of Weil

Question 6: You have had the opportunity to experience both the Anglo-Saxon and Italian receptions of Weil’s thinking. What do you think are the greatest differences between the two?

Fiori: Above all, I remember Patricia Little, whom I met in 1972 at Tremblay-sur-Mauldre, a long-time member of l’Association. She has edited a large Weilian bibliography and has been (and still is) collaborating with the journal Cahiers Simone Weil.

In the United States., the American Weil Society is active and has held annual conferences on her since 1981. Then there is the English translation of L’Enracinement as The Need for Roots (1952). The author of the preface in the English edition was T.S. Eliot, who was one of the first to study her and recognize her deep spirituality. Then there’s Sir Richard Rees, a scholar and translator of Simone Weil and someone whom Cristina Campo knew.

At the same time, in Italy, Adriano Olivetti was publishing La Condizione Operaia (1952) and La Prima Radice (1954) translated by Franco Fortini in his own Edizioni di Comunità. However, Attesa di Dio was released by the publisher Casini in 1954.

Perhaps the biggest difference between the two was this: above all, Italian scholars were interested in Simone’s social experience and work-life, while the English-speaking writers published relatively early on (1965, translated by Richard Rees) things like Weil’s letters. As the years progressed, I got the impression that Anglo-Saxon interest in her has waned whereas it hasn’t for Italians. In Italy, the publisher Adelphi has basically released all of Weil’s work from the editions of Cahiers in four volumes (translated and collected by Giancarlo Gaeta and later in collaboration with Maria Concetta Sala). Today in Italy there’s a tidal wave of translations being worked on and essays written with work picking up the pace in the last few years.

Maybe the most significant difference is the less passionate regard Anglo-Saxons have for Weil.

Paradoxical Concepts of Friendship

Question 7: As you noted in Storia di un’amicizia, on the concept of “friendship” Weil writes: “L’amitié ne se recherche pas, ne se rêve pas, ne se desire pas; elle s’exerce (c’est une vertu).” [“Friendship is not sought, is not dreamed of, is not desired; it is exercised (it is a virtue)”.]

I would say you could extend this to Murdoch as well. You also spoke of Murdoch’s relationship with Weil in terms of a friendship outside of time and space. In the same way, you spoke of a friendship with Murdoch, this time within the fabric of space and time. For some Weil scholars (and also those of Murdoch), a certain paradox emerges: on the one hand, there’s the academic need to conduct the most impartial research possible, and on the other hand, there’s often a very extensive personal involvement. What do you think of this dichotomy when it comes to research?

Fiori: Research isn’t something that comes to an end, rather it’s an experience to be treated patiently and respectfully. Personal involvement is a necessary implication, especially in a case like Simone Weil’s, or else it would be obsolete history. When it comes to the topic of friendship, for me, it’s similar to the main emotion between parents and children, husband and wife, and lovers. There’s a deep involvement with the person you wish, with all your heart, to paint a portrait of and to recognize in all her colors. Then again, there is the need for impartial and impersonal research. The two are indispensable qualities when searching for an understanding. They are instinctive qualities that stem from the desire to uncover a loved person, who has given you a lot, to thank them, and to spread their beauty. ‘I said instinctive, but this desire to search for an understanding you can’t feel it for everyone nor can you force it either, but you can perfect it.

A Terrible Struggle

Question 8: It’s evident even today that readers see Simone Weil as a lively source, and in some cases they find in her a kindred “vocation,” to use a term you employed referring to your Morante article. You speak of “existential friendships.” At the same time, it seems difficult to avoid associating the figure of Weil with a certain idea of solitude, in both her life and thinking. She once wrote to Gustave Thibon: “I am not a person with whom it would be good to link one’s destiny.” [Joseph Marie Perrin & Gustave Thibon, Simone Weil as We Knew Her (2003 ed.), p. XV] What do you make of that statement?

Fiori: It’s closely tied to the previous one. Simone’s statement is born from her longing for perfection, tied to her awareness of having a mission: overcome the bad within her and the world and save it. A terrible struggle — whom to share it with? There was no other option but to continue on alone. Her pride prevented her from hoping.

There is a reason for her solitude. Her views were tied to her sadness in the face of the world’s evil. Of course, she was alone, as a genius and a woman. She had a difficult character. If I had met her in real life, we probably would have argued. I wouldn’t have managed to understand her prophetic thoughts, which enrich us today and will enrich us for many years to come. Woman-genius: two grounds for loneliness. She had a genius for understanding present and future events which made her a stranger, someone incomprehensible to others. As a woman, she became even more of a stranger by her absolute lack of diplomacy (which she shared with André, and about which his wife Eveline said “Il n’est pas diplomate pour deux sous”). She wouldn’t allow for any compromise. Her destiny: who could share it with her? From here, it followed the impossibility of uniting her destiny to anyone else’s, all made worse by an antipathy for herself as a woman.

On Baptism, Contradictions and “the Virtue of Hope”

Question 9: In your opinion, how important is it that Weil never got baptized?

Fiori: I will reply with the words that Pope Paul VI said to Gustave Thibon and which Thibon wrote in his memoirs: “I am sorry I could not canonize her as she was not baptized.” A great disappointment I share deeply. She would have been revered by many who would have begged for her to cure the soul thirsting for light.

Question 10: You wrote: “She has been able to preserve all the complexity of her contradictions”: What did you mean exactly? Could you tell us a little more?

Fiori: It was mainly about the major contradiction between her great love of Christ and the impossibility of her getting baptized. Maybe there’s a lot here about her inability to make herself happy, a complacency in sacrifice. Today, this saddens me and I find that such a capacity to conserve, to save all of her contradictions, is related to an excess of pride, a lack of hope. The fact that she has been able to preserve all her contradictions is connected to her character and her independence.

As I think about it more deeply after many years, I’m sad about this tendency of hers that prevented her from joining in on mass (she remained “on the threshold” like the catechumens) and all the rites of the Catholic faith. All of this could have provided some comfort and consolation in the face of the suffering of the world that affected her so greatly. She missed the “virtue of hope,” maybe the most difficult to practice out of the three theological virtues.

“I’m a philosopher and I’m interested in humanity”

Question 11: In the chapter of your biography titled, “Loneliness in London,” you paint a realistic, though dark, picture of Weil’s demise. But soon enough Gustave Thibon resurrected her in the form of a book she never wrote and thereafter she became something of a saint-like figure. What is your sense of all of this? Does it not seem rather unWeil?

Fiori: The generous grounds for not wanting to separate herself “from the immense and afflicted mass of non-believers” is what makes her sacrifice beautiful and at the same time is what affirms her faith. In this respect, Simone Weil is unique and provokes gratitude and emotion. The insurmountable obstacle that got in the way of her getting baptized was the pride of her loyalty towards herself, towards her own questions which she experienced violently.

They found her unconscious in her room and brought her to Middlesex Hospital. She had worked for the world, for those of yesterday and those of today, and the result of her work was l’Enracinement.

Dr. Roberts used to go crazy with his difficult and touchy patient. He was quite bitter about his incurable patient and never wanted to agree to an interview about her. The letter I wrote him asking for information was the only one I ever had returned intact. From the hospital, Simone was sent to Ashford, in the Kent countryside, near London. Upon entering the room prepared for her she said: “What a beautiful little room to die in.” To the question of “Religion” on the entry form she answered: “I’m a philosopher and I’m interested in humanity.”

Weil’s way of thinking was a new manner with which to question one’s self about God, Christ, and religion. New but at the same time ancient, reconnected to Medieval times for the beauty of the cathedrals. She didn’t feel worthy to take communion, moreover, sometimes she wouldn’t even enter the church but would attend Mass from the door, like the catechumen. Perrin defined her as “mystic ante litteram.” If she had been baptized, Pope Paul VI would have canonized her (he looked back on not being able to do so with regret). Giuseppe Roncalli, when he was an apostolic nuncio in Paris, once said: “How I love this soul” and he wrote a letter to Simone’s parents. Though he would have liked to have met them, it never happened.

“The others’ suffering clutched my solitude”

[GF continued] Work colleagues and old friends like Maurice Schumann came to see her as did her landlady, who was very fond of her because of the care Simone had taken in helping her son with his studies. The Catholic priest invited to preside over her funeral service missed his train and didn’t attend. Her grave was in the Catholic section, it was a pauper’s grave, a grave in the poor people’s area, subject to disappearance as others could be buried on top of her.

Leslie Paul fixed that and bought a grave for 12 pounds. A theologian, poet, and Anglican minister, he first met Weil in 1938 (when I met him he told me he had walked the same road as Simone). Leslie gifted me a small rhus-typhina plant, which is still in my garden. He wrote the only comprehensible reflection on the woman Simone Weil in his poem, “Lady whose grave I own.” [see Leslie Paul, Journey to Connemara and Other Poems (Outposts Publications, Walton-on-Thames, 1972).] Here, after conjuring an impossible Simone struggling with husbands and prams, he posed the final question: “Was this the real affliction, / The cross you had to bear,/ That you were simply what you were?”

When I visited the grave in 1975 I found the words of an unknown writer, “la mia solitudine l’altrui dolore ghermiva fino alla morte” (“The others’ suffering clutched my solitude”) (in Italian), signed C.M. Nobody ever found out who it was and the message has since disappeared.

I also remember the sweet old man who visited his wife’s grave every day. He told me many visitors came for Simone, “Ah! The brave young lady.” Even if we weren’t talking about Weil, it was as if she was still hanging around us, protecting us.

Iris Murdoch thought that Simone wanted to “transform humanity.” During the last phase of her life in France, Simone spent time with a group of scholars and teachers and Father Perrin was their spiritual leader. Madeleine Marcault was one of our dear friends; she lived in Florence for a long time because her father taught at the French Institute, the “Grenoble,” which my mother and I also used to visit. She converted to Catholicism and became Franciscan of the Third Order. She also used to attend those meetings in Marseilles organized by Father Perrin together with Weil. In these meetings, Marcault recalls that Weil “seemed so unhappy, as if she just wanted to die.” That’s what Marcault told me. She portrayed Simone with a sense of incurable anguish, that would probably be still the same if confronted with today’s world. Such sensibility is rare.

[Back to Thibon]

In that sense, what Gustave Thibon wrote about Weil points to an understanding one needs to have; it’s not far off from her, no. It’s not far because Simone wrote [in Écrits de Londres] that sanctity is “le minimum pour un chrétien” [“the minimum for a Christian”]. I think that in her painful prayer (later collected in “Connaissance Surnaturelle”), where she asks for everything to be taken away from her to be given to others, she was certainly aspiring to sanctity.

The book (Gravity and Grace edited by Thibon) that gathers Weil’s thoughts had and still has the great merit of putting us in violent contact with Weil. This book was needed when it came out and was avidly read. We need it again today. It allows the reader to know of a unique, passionate, particular, and genuine thinker. Never before was the pesanteur (gravity) that drags us down and rules the earth ever more accurately explored or ever better described so as the grace that descends if we pray on our hunger for the good, of which Simone always wrote of in her work.

Simone’s “violent” and “volcanic” side: “You can’t argue with her”

Question 12: You wrote that your biography is not so much a study as it is an immersion because Weil is too eternally young and violent (“éternellement jeune et violente”). This insistence on Weil’s “violent” side appears a few more times as when you mention that Alain taught her to channel the violence that she felt in herself through writing. Or when you note that the character of Renaud in Venice Saved is a portrayal of the “volcanic” side of her personality.

Could you tell us more about this side of Weil and how you think it may have influenced her philosophy?

Fiori: Too eternally young — young and violent. Yes, that’s how I see her. She was not an aesthete, she wanted to be clear; she wanted to understand the evil that unfurls between two poles, the indifference and the excess of partisanship, and the fanaticism of it all (Alain was her supreme teacher in this). Her philosophy was tied to her being, both sensitive and violent. I’ll say it again: Eveline Weil used to say this about her husband André: “Il n’est pas diplomate pour deux sous” (“He is not two cents of a diplomat”). And that was how Simone was too.

We are back at the “she wanted to change the world.” The sensibility and also the strength of the convictions that permeated her genius can help us in regard to how we want and are able to change the world around us, at least a little. She wanted too many things to change, and quickly. Here, impatience took over, and even a certain authoritarianism: the volcanic side of her nature which was also very proud. “You can’t argue with her, she always wants to be right” Lévi-Strauss once said. Even so, she attracts us and speaks to our hearts and minds. Her scope is vast, of many interests, scattered for all of us like a sowing of seeds. She is fascinating; she takes us out of cliché. Let’s listen to her when and as much as we can if only because we stand to learn something new.

You can’t take her like an object and place her in front of you to study. At least it was like that for me: you live with her, you talk to her and you suffer together about the suffering of the world. That’s why it’s immersion. From when I was young, from age 24, from my first encounter with Waiting on God, she’s been by my side, and I’ve felt her presence throughout my life. If I think back to my past, I’ve always been alongside her. There is that willingness to spread knowledge about the matter of human relationships, this yes, and in prayer, and trying to learn her great lesson of “attention.”

Her attention is like a sky that soothes the peaks of her passion for understanding, which is the essence of her vulcanism, pure passion. Weil’s attention guides her in sharing her discoveries with us. The greatest among her discoveries is the “needs of human beings”. And in order to satisfy these needs, she conceives the idea of a new Constitution.

“It’s true: she did let herself starve to death”

Question 13: The next question is from Professor E. Jane Doering, I’ll put it to you exactly as it was forwarded to me:

Ms. Fiori, thank you for your willingness to answer our questions concerning the subject of your “inner biography” of Simone Weil, which gives us some original perspectives. We are grateful for your work. I use it in my classes on this important French philosopher.

I’m interested in your reasoning that presented Simone Weil’s death as a suicide despite all the other opinions explained later in the same chapter. This position is important as to the impression it leaves in the minds of students. If you were to rewrite your biography, would you take the same position as to this complex and ambiguous death? If so, why?

Fiori: I think Simone died in her sleep on the 24th of August 1943. The news was given to André who told his parents. In the papers, they wrote that she let herself starve to death. And it’s true: she did let herself starve to death. She would constantly say: “I can’t eat while children are starving because of war.” Déodat Roché, who had met her when she was in Marseille, told me when we met: “If you don’t eat you get malnourished and you die.”

The problem with food had begun in the last stages of breastfeeding which Selma Weil wanted to continue on with although she was heavily sick with the flu. It seems that Simone said in her last few days: “If I only had a nice juicy peach, or purée like my mum used to make, I’d eat now.”

When Simone Weil went into her room in Ashford, after frustrating Dr. Roberts, who was resentful of her childish cheekiness and her desire to not be cured (here’s the agony of her loneliness also as a woman) there was nothing more that could be done, and she knew it too (“what a lovely little room to die in”). And let’s not forget the impression Madeleine Marcault had when she met her in Marseille: an unhappy woman who just wanted to die. She didn’t love life; she was tormented by the ills of the world, by the impossibility of changing it.

Because of this, I would still start my book like that, with the newspaper headline. As for the rest, I think we’re not able to understand, and that we won’t ever be able to understand until the end.

Attesa di Dio: “I had never read a book like that before”

Question 14: The first book of Weil’s you state having read is Attente de Dieu, thanks to a recommendation by a family friend. This event dates back to the 1960s, right? From that first reading, what touched you the most? What definitively left its mark and why?

Fiori: A friend of ours, the lawyer Ugo Fortini (a great reader always at the forefront of anything important that was being released) spoke to us about Attesa di Dio, available in Italy from 1954. He described it as “an extraordinary book by an incredible woman, Simone Weil.” He’d lost his wife Vittoria to the bombing of Florence in 1943. Just that day, she’d gone to Florence with her sister from the countryside to where they’d been evacuated. Vittoria had a strong Catholic faith; they were happy and in love. Then, he, an agnostic, wanted to experience her faith and in Attesa di Dio he’d found a companion in her “similar situation.” He explained it to us so well that I (then about 24) was deeply moved and wanted that book. Although I had been immersed in French culture, as I said, since I was a child, I didn’t know Simone Weil.

At the time we were hosting a friend, five years older than me, who was studying for the state teaching exam. She wanted to buy me a present so I asked her to get me Attente de Dieu as a present. I had never read a book like that before that dealt with the root problem of faith but also expressed Christian faith.

“Human relationships interested me”

Question 15: Could you tell us something about your work on your thesis when you were still a student?

Fiori: I did my thesis on John Galsworthy’s The Forsyte Saga. My emphasis was in literature and philosophy, specializing in contemporary literature. I particularly liked the novel, the title was La saga dei Forsyte come crisi e trasfigurazione del vittorianesimo. I discovered it myself with the help of classmate Enrico Andreini, who later became my husband, but is no longer with us.

Human relationships interested me, it was my hope they would be vividly lived: all about friendship, understanding, sharing the days, readings, discoveries, chatting, confiding in each other, and in writing letters to one another. That’s what I wanted in life and also with the authors (I also believed a lot in women’s writing) I came to know through their characters. This wasn’t very well understood by either my thesis tutor or his assistant. I’m very subjective in my method of working and I believe in a friendly relationship with the author because every character in a novel mirrors them. Characters are for them their closest friends. This was what inspired my thoughts when I was a teenager. And then which influenced my books, from Weil’s biography to my book on Anna Maria Ortese.

Question 16: In your article for Cahiers you noted that your favorite book by Morante is L’isola di Arturo (1957). Morante’s notes on Weil’s books seem to be taken at the beginning of the 1960s, a decidedly difficult year for Morante due to her separation from Moravia and the death of Bill Morrow. Also Giorgio Agamben, in an interview with Repubblica, reports to have introduced Morante to Weil’s life and work around 1963/64.

You quite rightly speak of a “prehistory” in the Weil-Morante relationship. Do you think, however, that when Morante was working on L’isola di Arturo she had already come across Weil’s philosophy? Alberto Moravia (Morante’s husband), for example, already refers to Weil in 1952 commenting on the film Roberto Rossellini’s Europa 51. What do you think about this hypothesis?

Fiori: Your hypothesis seems correct to me. Europa 51 portrays a Weilian woman. On the other hand, the marriage of Elsa Morante and Alberto Moravia was a profound union; the celebration of the wedding in a religious ceremony celebrated by Elsa’s spiritual consultant was strongly desired by her. The choice of deepening her knowledge of Simone isn’t an obvious or common thing.

On Weil, Murdoch, and Morante

Question 17: Cesare Garboli, in his introduction to Morante’s Pro o contro la bomba atomica, mentions what he defines Morante’s progressive surrender to la pesanteur as something connected to a sense of guilt. You spoke about this in your article on Weil-Morante. Did you also find this tendency of Morante’s towards “la pesanteur” in Murdoch?

Fiori: I think, if I remember well, that Murdoch took la pesanteur (gravity) for granted. In fact, she didn’t even consider it. Iris Murdoch described her characters and their relationships without judging them. She portrayed them through the reality of their own feelings: there’s goodness, there’s malice, there’s generosity, and there’s selfishness, although often more malice and selfishness than goodness and generosity. One moves forward in life and in their feelings (human relationships are always at the forefront for her), faltering, making mistakes, often failing more than succeeding. But there are also very good people (like the mother in An Unofficial Rose) who generally suffer a lot because they haven’t been either loved or understood (the adolescent child, unfair and mean, rebels against the mother, like most of Murdoch’s adolescents).

Question 18: Personally, I believe what binds Weil, Murdoch, and Morante together is an affinity, as you call it, “vocazione per la verità.” But what do you think is the biggest difference between Murdoch’s reading of Weil and Morante’s? And in a wider context, which major differences would you perceive between the two women and their poetry?

Fiori: I know too little about Iris Murdoch’s reading of Weil. To me, it seems that Morante is more profoundly taken by Weil. You just have to read her profound and touching poem Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini. Weil, as a woman and as a contemporary thinker, is a perfect example of Morante’s “felici pochi” (the Happy-Few).. She can give us a lot of perspective about life around us, of the pain in our time, which she fully suffered (“sorelluccia inviolata / ultima colomba dei diluvi stroncata”).

Elsa Morante lives together with Simone Weil, she would like to have the strength to follow her principles in life, “but it’s not possible.” Iris Murdoch doesn’t pass any moral judgments; ultimately she thinks it’s impossible to change human beings, to change life events which are usually self-inflicted. Major differences between the two poets: I find that animals and nature are more present in Elsa Morante, at least in relation to L’isola di Arturo. Of Murdoch, I remember much more about the inside of houses and cities.

Other major differences between the two women: Elsa Morante still has a childlike innocence to her, more a sense of nature, and more love for animals than Iris Murdoch who is more of a city person. Morante is more instinctive than Murdoch (let’s think of Arturo, who is herself, and of Nunziata, an extremely young mother, who has a solitary and unaffectionate husband). In life, Elsa Morante seems more cautious and aloof, quite melancholic and reserved, settled in her convictions and denials (such is the way she came across on the phone). For Iris Murdoch I described the impression I got when she came to my house and when I went to hers; she’s more cheerful and carefree than Morante, very strong-willed and determined in her work as a writer (I don’t know her as a philosophy tutor). She’s less poetic and instinctive than Morante.

“A different kind of woman”

Question 19: Why did you choose to define Weil as a “different kind of woman”? In what key sense was she different?

Fiori: In building my opinion, her psychoanalyst cousin Raymonde Weil played a part. She was orphaned early on in life and spent a lot of time in the Weil household. Simone felt very sorry she’d lost her mother and saw her as an unfortunate little sister she had to protect. When, however, as a teenager, she began to speak about dances and clothes just like the other girls, she “couldn’t talk to her about it” and Simone didn’t care in the slightest.

Her genius always gave her colossal thoughts since she was a child, nurtured by her sensibility; it made her want to change the world more. Then there was her willpower, which she began to form after Alain’s first judgment of her class work (as he was giving back corrected homework he said: “I have illegible work here”). That prompted her to create nice handwriting (childish looking). In her Cahiers, we find references to male geniuses, for example, Leonardo, who in France they call “Vinci.” Her life choices — from the first, becoming a laborer, to the last, proposing to parachute into France for a dangerous mission — reveal her desire to neglect herself as a traditional sort of woman. Alain, who had her as a student at Lycée Henri IV to prepare for École Normale Supérieure, defined her as “far superior to anyone of that generation.” She used to say that for a marriage to work you needed two saints or at least one. “My sister wanted to change the world” is what André had told me. To the very end, that is what consumed her short life and made her feel the urgent need to leave us a new World Constitution, which, in order to write, she locked herself in her London office.

Frailty, Force and Feminism

Question 20: It seems to me that criticisms of sentimentalism, pessimism, and masochism, on the one hand, and misogyny on the other hand, turned against all three thinkers (Weil, Murdoch and Morante). Furthermore, in Murdoch’s and Morante’s novels women are often represented as things, animals, or plants.

How, if at all, would you connect this with Weil’s philosophy and the idea of frailty as opposed to “force”? How might we reply to those who saw in this a certain “sympathy” for masochistic or misogynistic views that are incompatible with the modern struggle for equality?

Fiori: Simone Weil pays continuous attention to her fundamental choices, which are unique for a woman of her social status — for example, her work in the factory. She takes these thoughts as the foundations for her project of a new world constitution. She lives for her ideas and they feed her principles for a reconstruction of the world. Weil’s idea is that frailty is the real force, in this acceptance of the human condition, linked to the acceptance of enduring pain. Frailty is forgiveness. “The modern struggle for equality” doesn’t interest any of the three thinkers, who definitely follow, it seems to me, the path imagined, which is full, especially in Weil’s case, of difficulties for women. Expressing their vision of the world, that is what motivated them and they did it at all costs.

Question 21: On the same theme, you wrote about Weil: “Her mythical figure of a woman is Violetta in Venise Sauvée.”Tell us a bit more.

Fiori: Violetta, a mythical female figure, was protected and cared for by Weil like a nice dream; she is part of her deep femininity, I think. It is what she couldn’t be and didn’t want to be in life.

Attentive Wonders

Question 22: You spoke at a book presentation once, in quite a Murdochian manner, about the dryness of our present times and mentioned the idea of “wonder.” Could you say something about the connection between wonder and Weil’s idea of attention? And between inattention and dryness?

Fiori: Living with “attention” means discovering the “wonder,” meaning truly listening to the continuous questions that things, situations, and people pose to us. It’s not easy, but we can try. Life tests us perennially in that sense. Every encounter, even a fleeting one, is a discovery. If we fail, the result is complete indifference, which is linked to great dryness.

Conclusion

Question 23: To conclude, do you have any advice for young Weilian scholars who find themselves trying to speak about transcendence, the absolute value of justice, the good, and beauty in a modern world so often alien to all of these concepts?

Fiori: My advice is to continue to study Weil, take courage from her despite everything, and love and desire the Good. We must also try to overcome evil (superficiality, indolence, pessimism), first in ourselves in order to have or increase our knowledge of the existence of evil in the world. This is the work of attention and of the sensibility in observing our world, in the consciousness of ourselves and others. It is important to recognize our own culture and understand the reasons behind its literary and artistic taste and of the past and the present. Finally, we must build patiently, one day at a time, in order to have a better future.

Bibliography

- Campo, Cristina. Sotto falso nome. Milano, Adelphi, 1998

- Cristina Campo: la disciplina della gioia : con le lettere a John Lindsay Opie, a cura di Maria Pertile e Giovanna Scarca. Villa Verucchio, Pazzini, 2021

- L’Europa di Simone Weil : filosofia e nuove istituzioni, a cura di Rita Fulco e Tommaso Greco. Macerata, Quodlibet, 2019

- Fiori, Gabriella. Simone Weil : biografia di un pensiero. Milano, Garzanti, 1981 (3. ed. 2006)

- _______, Simone Weil : una donna assoluta. Milano, La tartaruga, 1991

- ______,. Simone Weil : une femme absolue. Paris, Éd. du Félin, 1987

- _______, Anna Maria Ortese, o dell’indipendenza poetica. Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2002

- _______, – Graziosi, Mariolina – Marchetti, Adriano. Simone Weil : poesia e impegno. Milano, UNICOPLI, 2003

- Negri, Federica. La passione della purezza : Simone Weil e Cristina Campo. Padova, Il Poligrafo, 2005

- Perrin, J.-M. – Thibon, Gustave. Simone Weil, telle que nous l’avons connue. Paris, La Colombe, 1952

- Weil, Simone. Gateway to God. Ed. by David Raper with the collaboration of Malcolm Muggeridge and Vernon Sproxton. London, Fontana, 1974 [contiene la poesia di Leslie Paul]

About the Interviewer

Michela Dianetti is Attention’s foreign correspondent for Italy and a graduate student at the University of Galway.

5 Recommendations