Marie-Magdeleine Davy and the Memory of Simone Weil

Brenna MooreThe first book in English to be published on Simone Weil was Marie-Magdeleine Davy’s 1951 The Mysticism of Simone Weil (translated by Cynthia Rowland). It was a slim volume of 84 pages published by Rockliff Press in London and then by Beacon Press in Boston. Davy was a French scholar of mysticism and active in the resistance to Nazism. Notably, she had also been an acquaintance of Weil’s.

Her book was based on a 1950 French article Davy wrote in the journal, L’âge nouveau, “A Propos de Simone Weil.” Most of Davy’s works were published in her native French, and her Weil book appeared as Introduction au message de Simone Weil later with Plon publishing house in 1954.

Davy met Weil at the home of Marcel Moré sometime in the late 1930s. Soon after Weil’s death in 1943, Davy was part of the early effort of family and friends, especially Weil’s mother, who gathered Weil’s papers. They began to circulate accounts attesting to Weil’s experiments with solidarity and the unusual depth of her spirituality.

Davy had been friendly with Weil’s parents. She felt that the other writers who were beginning to solidify Weil’s reputation did not have it quite right. For example, Davy was critical of Marcel Moré’s 1950 article in Dieu Vivant that focused on Weil’s alleged obsessive anti-materialism and the extremities of her diet.

Yet Davy also thought that Fr. Joseph-Marie Perrin’s 1950 preface to the collection of her writings he edited, Attente de Dieu, was too timid, cautious, too familiarly Christian, and missed Weil’s expansiveness and radicalism. She wanted to set the record straight. Two more books by Davy on Weil followed her first, and countless essays and articles.

Spiritual Radiance

Davy’s depiction of Weil often veers away from the content of her ideas and towards the spiritual impact Weil had on others. Weil “shed” as Davy put it, “a spiritual radiance” around herself. “No character of our age has created such an intensity of spiritual radiance as Simone Weil.” She “carried within herself a flame,” Davy continued, “that scorched others. She disturbed the tranquility of things and troubled the security of bourgeoisie society.”

“She lived in a dimension of such profundity that few beings can reach it. When one lives in such a dimension, time no longer exists; in its place there is a tapestry, upon which everything can be read, the past, current events and what will happen. She simply knew. It was the end of wandering. When I speak of wandering, I mean Adam and Eve, full of fear and condemed to wander without any direction. She understood that Christianity was to be lived internally, that the external does not count. All values can then be attained, even those involving one’s country and the world.” — Marie-Magdeleine Davy

Quoted in Gabriella Fiori, Simone Weil (University of Georgia Press, 1989) 307.

It wasn’t, however, all hagiographic; Davy was a rare scholar of Christianity who reckoned seriously with anti-Semitism during and immediately following the war. Davy wrote, early on, that Weil’s greatest shortcoming was that in her life she never truly understood her own Jewish heritage.

Davy often described how one had to experience Simone Weil, in some way, to “get” her. To that end, Davy undertook a particularly creative and massive effort to make Weil known to the world – a place entirely outside the world of discourse and writing, however, and one aimed to recapture something more experiential.

Maison Simone Weil

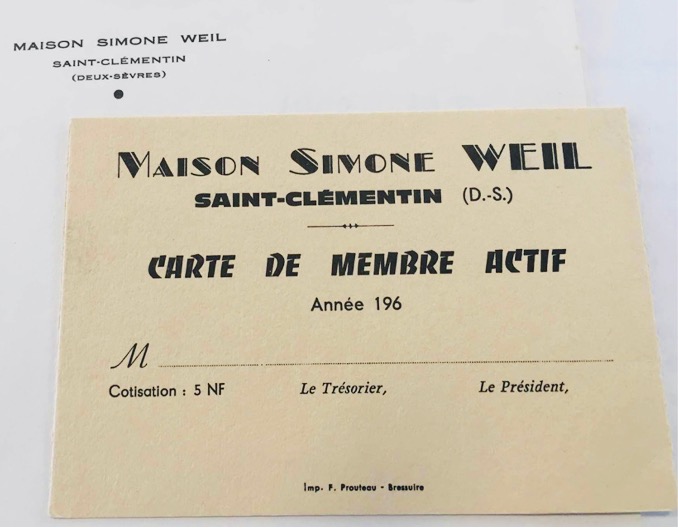

In the late 1950s, Davy inherited a large chalet from a relative, an old twenty-two-bedroom estate in the French countryside called La Roche aux Moines. In time Davy turned the chalet into a dormitory for international students who enrolled in a new summer program Davy created in honor of her late friend. In 1962, Maison Simone Weil was born. Students from all over the world – some received a scholarship, some paid a fee – came to hear lectures on topics like existentialism and the arts. Others listened to lectures on “the sense of the sacred.” Yet others gathered to hear talks on “spirituality.” It was a utopian experiment in cosmopolitan spirituality, one inspired by Weil and endowed with the optimistic atmosphere of the global 1960s.

Nothing has ever been published on Maison Simone Weil – it was only when I was going through the materials at Marie Magdeleine Davy’s archive that I first learned of it. I found elaborate plans for the meal schedules, countless files of correspondence arranging the logistics for speakers, the stationary emblazoned with Weil’s name, photos of students in conversation, and tender notes from program alumni keeping in touch with Davy.

When we think of the “influence” that thinkers like Weil and other philosophers have had, we often look to the history of ideas; we track signs of thought, or even style, in books and articles (or even political ideologies) and date them. But some, as Davy tried to explain to us about Simone Weil, do not so entirely locate themselves at the level of conscious philosophical reflection. Experience was key for Davy. She wanted to capture some of that for others, the young people who came to Maison Simone Weil.

Experiencing the Radical Weil

Perhaps such experiences helped Davy express something she couldn’t always put her finger on. Simone Weil was a kindred spirit, a fellow traveler of the inner life, someone like her who intensely identified with those suffering during the war and was deeply drawn into spheres of the world few women at the time had entered: Davy in Catholic monastic theology, and Weil in philosophy, even military and factory work.

Davy and Weil never called themselves feminists. Nonetheless, they lived their lives in radical separation from mainstream norms available to women at the time. For Davy, Weil was a brilliant thinker, reader, and writer, but her appeal was not simply cognitive. There was “The expression in her eyes,” as Davy once put it. The allure of Weil came to Davy early on, which might explain why she never felt quite satisfied with books or essays in telling the Weil story. Davy was after something else. That perspective should prompt those drawn to Weil’s life and legacy to consider other paths beyond the mere written word.

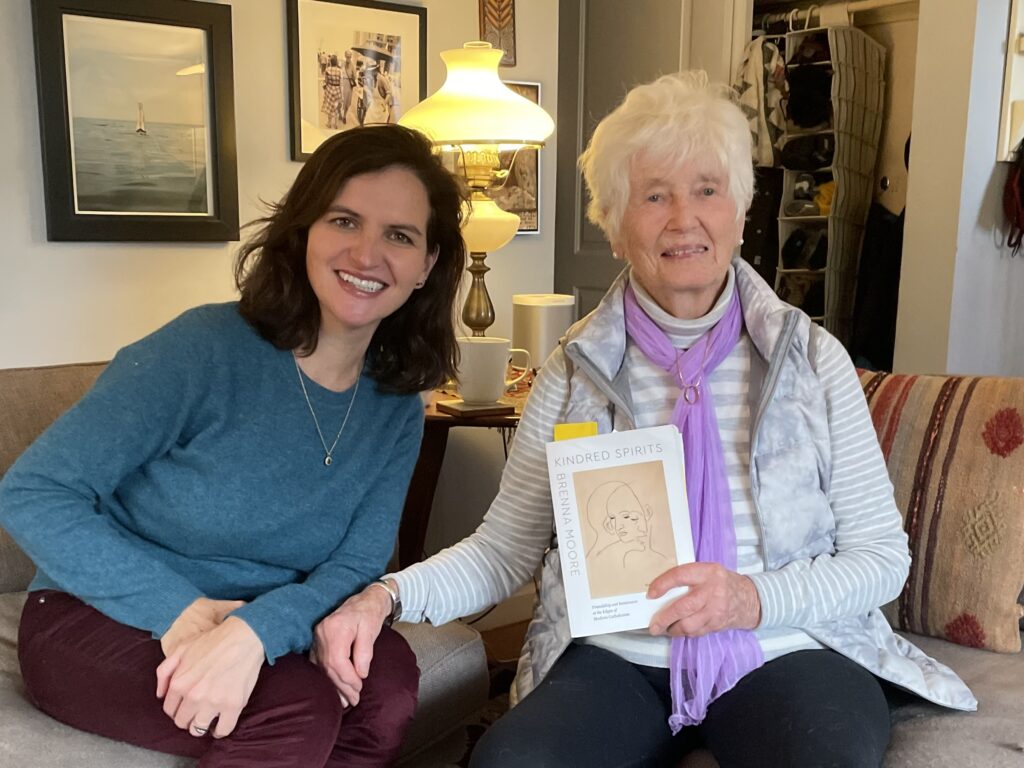

Brenna Moore is a professor in the Department of Theology at Fordham University. This essay draws from chapter 4 of her new book, Kindred Spirits: Friendship and Resistance at the Edges of Modern Catholicism (2021).

6 Recommendations