Simone Weil’s Summary Notes “Concerning the Pythagorean Doctrine”

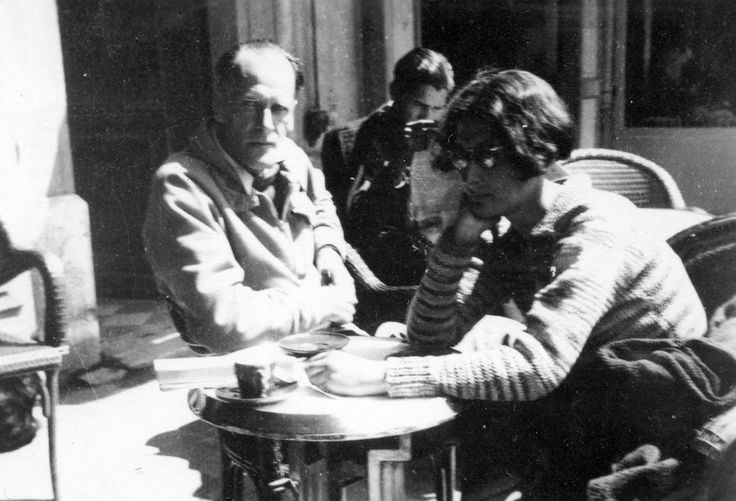

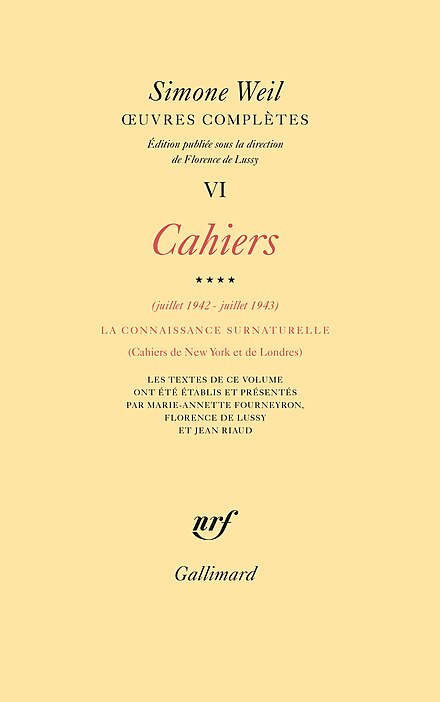

Translated and introduced by D.K. Levy and Marina BarabasWe present below a new translation of summary notes Simone Weil made from a lengthy essay she wrote and sent to her friend and spiritual mentor, the Dominican priest, Joseph-Marie Perrin. The notes might serve as an aid to readers of that important essay “Concerning the Pythagorean Doctrine” (hereafter CPD in Simone Weil: Basic Writings).

“Concerning the Pythagorean Doctrine”

Simone Weil’s essay on what she called the Pythagorean doctrine may well be the most illuminating of her thinking, especially of her philosophical metaphysics. The essay shows the place Greek thought enjoyed in her thinking and her understanding of salvation as expressed in the language of Christianity. In it, Weil first presents a cosmogony borrowed from the Pythagoreans and elaborated by Plato, especially in his work Timaeus. She also adds Greek Stoic ideas to develop a conception of cosmic harmony as the basis of the order underlying the possibility of human experience. We should, she thinks, welcome and bring ourselves into accord with this order in our own lives. This would be for us a kind of salvation: a salvation that existence and the material world afford to us.

Weil then sketches a parallel cosmogony using Christian ideas and texts in the Gospels. She transposes the Greek principle of cosmic harmony to a conception of the harmony in the triune God, whose love and providence sustain the cosmic order on which every element in human experience depends. Weil is explicit (in a side note possibly addressed to Perrin, CPD, page 290) that her way of explicating material existence means that human beings do not have to await the Incarnation for their redemption or salvation. The existent, material world already contains salvation as a potential destiny for every human being through harmony with the cosmic order. In addition, Weil also finds within material existence explanations for suffering and sin.

The essay on the Pythagorean doctrine therefore does more than provide a metaphysical foundation for her thought. This same doctrine is also an account of how our unique, human faculties allow, at the limit, each of us to become attuned to the cosmic order of reality. Such an attuning will show itself in actions, which themselves accord with the cosmic order, whether conceived along Greek or Christian lines. The attuning that takes place in an individual does so by an intermediation between the individual and the cosmic order. The intermediation itself occurs by means of intermediaries. These intermediaries, when they are used in intermediation, create a connection from the natural world of existence to the supernatural—to the mode of pure being. These connections mediate between the natural and the supernatural. Under the right conditions, that mediation is apprehensible by human beings. Weil sets out how all such mediations by means of an intermediary together form a kind of ladder leading to contact with the supernatural, with the cosmic order.

These intermediaries are nonetheless mere material objects here below in the realm of existence. Geometry—with its material approximations of ideal shapes that can lead to necessary truths—is the example to which Weil turns in this essay and elsewhere, but strictly speaking it is no better than any other intermediary. So it is that the material world itself contains mechanisms for mediation, transparent images of cosmic truths, and the ladder to salvation, if only the right faculties are brought to bear upon them. As Weil writes, “Human thought and the universe constitute in this way the books of revelation par excellence, if the attention enlightened by love and faith knows how to decipher them.” (CPD, 293). Weil’s essay might for that reason be fairly described as a digest of her philosophical thought, given in a form that makes it a prism for separating her metaphysical and religious thinking.

The summary notes

Weil left Marseilles with her parents in May 1942 en route to New York. They had just under three weeks in Casablanca while they waited for their passage to New York. There Weil wrote this long essay over about two weeks before sending it to Father Perrin. Weil had left all her working notebooks in France with Gustave Thibon and so had to write this long Pythagorean essay without the benefit of drawing from the notes in her notebooks.

Probably before sending the essay, Weil made summary notes of its content in her new working notebook. This is notable because it was not her practice to summarize essays she had written, even long essays such as “Forms of the implicit love of God.” Many of Weil’s essays were distillations, the reworked formulations of ideas that had only been germinal in her working notebook. That is, most often she took ideas from her notebooks, elaborated them, and made them more cogent.

Being without her notebooks, one explanation for her making the summary of the essay might be that she wanted to record her ideas afresh in the new working notebook she had just started. The terseness of the summary notes militates against accepting this explanation as being at most partial. Her notes follow the structure of the essay quite closely, right down to numbering five of the forms of mediation outlined and explicated in the essay. With that in mind, a second explanation for the summary might be that Weil wanted to record the structure of scattered ideas that she had long nurtured in her notebooks but had never distilled and formed into a single articulation. That process—the writing of the essay—had perhaps inter-related her ideas to form a new complex or whole that she believed would be cogent to a reader other than herself. If that is right, then another explanation for making the summary notes is that Weil wanted to add this inter-related complex of ideas to her notebook for later consideration.

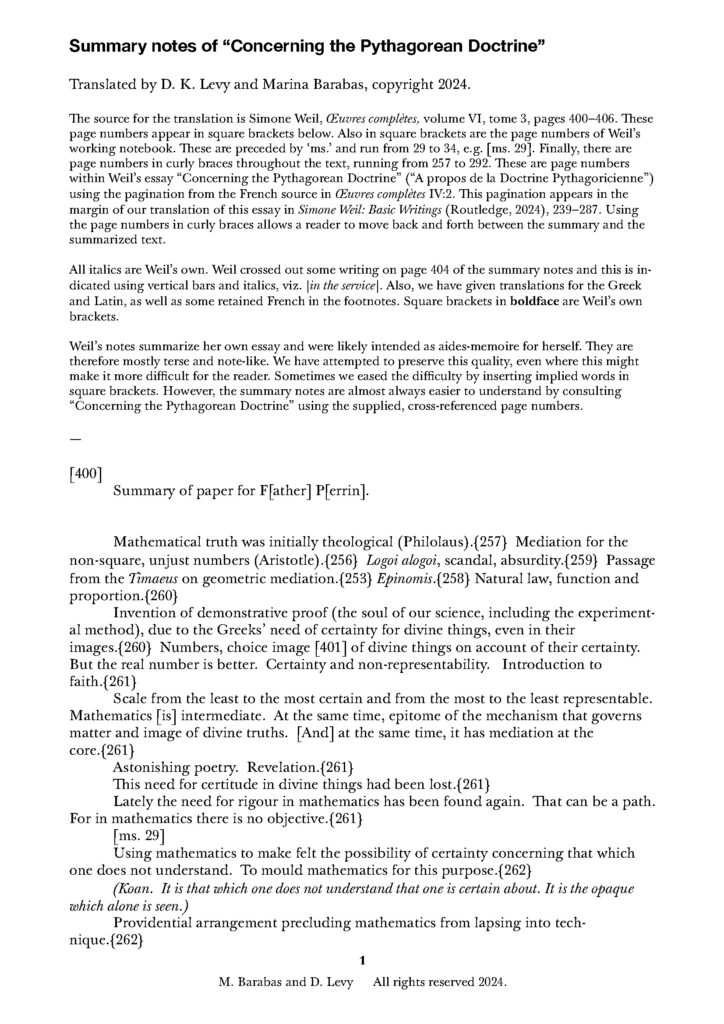

For the reader today, the summary notes she made afford several helpful possibilities. First, the summary is itself a guide to those ideas that Weil considered most interesting. An idea she omitted from the summary is probably one she judged neither novel nor interesting. Second, the summary is by its nature synoptical of the whole essay, providing a view of its overall structure and the movements in thought she intended for a reader. With the summary notes and the essay in hand, a reader can move out from the detail to survey the bigger picture before returning to the elaborated detail. It is to this end that we have added cross-referenced page numbers from the essay at the corresponding points in the summary notes. Third, in some cases a central point Weil wants to make in the essay is presented naked—shorn of context—in the summary notes, thereby making it easier to grasp. That is, in the summary notes her formulations are sometimes more direct, albeit more compact.

Certainly, reading Weil’s summary notes will not substitute for reading the essay. The notes can help a reader. However, they are not the only work connected to the essay “Concerning the Pythagoreans.” Alongside that essay, included in our Simone Weil: Basic Writings, we also published a translation of a first, short attempt she had made on her essay—titled “Sketch of the ‘Commentary on Pythagorean texts’.” The “Sketch” places more expository emphasis on the theological interpretation of geometry, while the summary notes put the emphasis on the inter-mediation in all things that are central in the completed essay. A reader who makes use of both will have two additional perspectives on the ideas in her essay that are so central and important to Weil’s thought.

_________________________________________

Weil’s Summary Notes

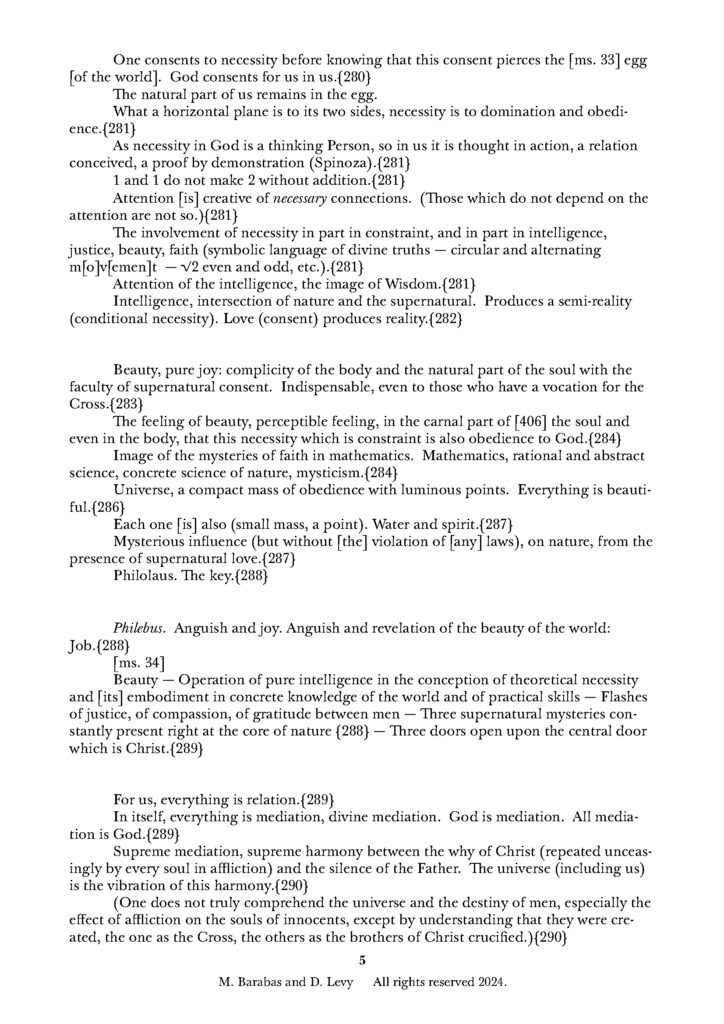

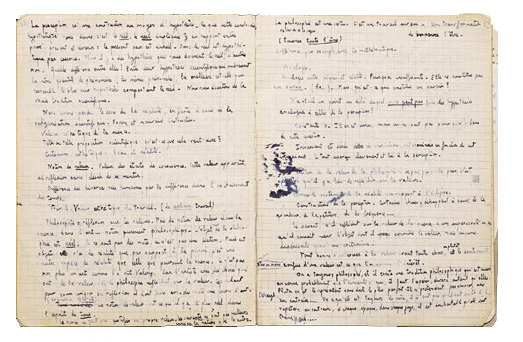

[The photographic image below is a random sample of Weil’s notebook entries.]

- Translated by D. K. Levy and Marina Barabas; introduction by Levy. See Levy and Barbas, eds. and trans., Simone Weil: Basic Writings (Routledge, 2024).