The Language of Limitation as the Key to Simone Weil’s Understanding of Beauty and Justice

Lawrence E. SchmidtThat which limits is God. ‘God is the measure of all things.’ It is God who prevents the sea from encroaching further than it should. We must do like him in the case of our own interior sea. We have got to become perfect obedience because we are not God. Christ, considered as man, was never anything else but perfect obedience. The non-limited principle in us must be obedient to what is the limiting principle, like the sea. This limiting principle comes from outside us. (N, I, 394)

Simone Weil argued throughout her life that the language of limitation (and obligation) rather than that of freedom (and rights) must color our understanding of all transcendental realities including beauty and justice. A proper conception of limit is the very principle of order in “the manifested world” (SN-F, 79). This principle was derived from the cosmologies of pre-Socratic thinkers like Anaximander and Philolaus.

According to Anaximander, an Ionian of the 6th century B.C., all things emerge out of the apeiron, or “unlimited,” and assume form precisely in being subjected to limit. The ontology of limit was later developed within the Pythagorean school (IC-PD, 151-201). Simone Weil elaborated on the content of this development in her lengthy discussion of Pythagoreanism which, according to Simone Pétrement, she wrote while she and her parents were on their way to New York and were quartered in a camp at Aïn-Seba on the outskirts of Casablanca. “In two large halls they slept on the cement floor, wrapped in their blankets” (P, 468). Every day Weil’s parents secured a chair for her so that she could write the essay in which she explained the importance of limitation.

An encounter with beauty and art

In a fragment she wrote a little later and which was included in Sur la Science (SLS, 275), Weil explained what she meant by limitation: “Only God (or whatever name one may choose) is without limits. (Under another aspect, relation is the law of the manifested world, and only God is without relation.) Man, who is of the world and who has a part in God, puts the unlimited and the absolute into the world, where they are error; this error is suffering and sin, and all human beings, even the most ignorant, are torn by this contradiction” (SLS, 250).

Weil argues that the experience of beauty makes it possible for human beings to recognize and accept the reality of the world, and to love it. The recognition of the beautiful consists of loving simply that a thing should be, “not wanting to tamper with it…” The beautiful calls forth consent to what is with all its limitations. Everything which exists, she observes, is, “by the chains of necessity subordinated to limit,” but “the very enslavement, which is necessity, or law, upon the plane of the intelligence, is beauty upon the plane immediately above, and is obedience in relation to God.” (IC-DL, 101). The beautiful confronts us with something to which we can ascribe no scrutable purpose, which, in fact, may even cause us to suffer, but which we nevertheless know to be good. This encounter calls forth consent to what is. In Weil’s words, “it is the beauty of the world which permits us to contemplate and to love necessity” (IC-PD, 190).

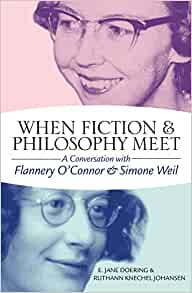

Jane Doering and Ruthann Knechel-Johansen have recently explained how Flannery O’Connor’s artistic vision corresponded in many respects to the account of beauty and art that Weil proposes (WHP). O’Connor wrote that “the novelist writes about what he sees on the surface, but his angle of vision is such that he begins to see before he gets to the surface and he continues to see after he has gone past it. He begins to see in the depths of himself, and it seems to me that his position there rests on what must certainly be the bedrock of all human experience — the experience of limitation…” (MM, 131-132).

One of Flannery O’Connor’s most remarkable stories is entitled “A View of the Woods.” Among other things the story is a kind of allegory of the great modern progressive society. It opens with the two main characters, Mr. Fortune and his granddaughter Mary, sitting on the hood of a Cadillac watching while a “machine systematically ate a square red hole in what had once been a cow pasture.” In the story’s first line of dialogue, Mr. Fortune says to Mary, “any fool that would let a cow pasture interfere with progress is not on my books” (TCS, 335). As the story unfolds we see that Mr. Fortune’s own daughter and her “idiot” husband are indeed among those who are “not on his books.” Mr. Fortune owns the land his daughter’s family lives on and he slowly parcels it out for development. He prides himself on his vision of progress and the story depicts, time and again, his ability to dismiss the protests and laments of his own family simply by going over, in his head, his grand idea of the future. This idea drives him onward carrying him to some inevitable destination.

The story itself grinds forward to its horrible conclusion (the killing of Mr. Fortune) with the ruthless logic of a Sophoclean tragedy. But at the point when we begin to sense the full dimensions of the darkness rushing in like flood waters, there is an extraordinary moment of stillness. Mr. Fortune sitting alone in his room goes back and forth to the window. The third time at the window “[t]he old man stared for some time, as if for a prolonged instant he were caught up out of the rattle of everything that led to the future and were held there in the midst of an uncomfortable mystery that he had not apprehended before” (TCS, 335). This moment is rather like those in the Iliad that Weil describes as moments of grace. It is a fleeting moment of recognition; in terms of the plot, it changes nothing. It would be a gross understatement to say that this story does not end happily, but the “uncomfortable mystery” is nevertheless established as part of the truth of the story.

In the experience of mystery we discover, that we are limited; we discover that we do not belong to ourselves. According to one’s perspective, this realization may be a source of raging frustration or sublime wisdom. This is intimated in O’Connor’s observation that “limitation and possibility mean about the same thing.” (TSPG, 7)

In the perception of beauty, in the contemplation of nature or great art, we see that the concordance of necessity and good exists on another plane from the one in which we know them to be contraries. Because Weil was so deeply sensitive to the reality of human suffering, she could not tolerate any confusion of these planes. She writes, “each phenomenon has two causes, of which one is its cause according to nature, that is, natural law; the second cause is in the providential ordering of the world, and it is never permissible to make use of one as an explanation upon the plane to which the other belongs” (IC-DL, 97). The beautiful, then, in revealing the full dimension of the paradox that is the relation of necessity and good, brings us to the threshold of consent. It allows us to accept what is as a sacrament, a mediation between the human and the Divine.

An “uncomfortable mystery”

Justice, on the other hand, moves us as human beings to accept obligation and limit in the relationship to another individual and to the collectivities that form the context of our social relations. Justice is not possible where a human being continues to see her or himself as the center of the universe, for such an illusion of perspective blinds one to the recognition of limits. So justice must have its ground outside the world, in that order of reality that appears to us as an “uncomfortable mystery.” The assertion of the self, bound up as it is in a web of illusion, must necessarily manifest itself as a denial of reality and, in particular, of the full existence of the other.

The failure to grasp the essential nature of limit in the order of reality results from an improper reading of the world. Such an improper reading is what lies behind human injustice. Conversely a proper reading binds one to a deeper moral principle that Weil spoke of in terms of obedience. In her Notebooks Weil made the following entry: “Reading. Just as in a piece of bread we read something to eat, and we set about eating it; so in such and such a group of circumstances we read an obligation; and we set about performing it” (N, I, 249). Weil, as a Platonist, associated the proper perception of reality with virtue. To perceive reality and to consent to it involves a sense of the real relationship of things. It involves being transported out of the basic animal narcissism that seeks to affirm its own powers by denying otherness.

A theoretical and spiritual impasse

There is, however, in addition to natural narcissism, another mechanism that militates against “the union of contraries.” This one functions on the political level. It is that matrix of illusion, ideology, power-struggle, oppression, and myth that so often constitutes the mechanism of social life. In her contemplation of the political Weil seemed to arrive at a theoretical and spiritual impasse: the human heart perpetually yearns for justice while in the social world necessity reigns supreme. With a series of mystical experiences at Assisi and Solesmes she began to find a way through this impasse toward a doctrine of grace. But the consent that issues in the openness of the soul to grace cannot come about without taking the full measure of evil in the world. As Weil wrote, “only he who knows the empire of might and knows how not to respect it is capable of love and justice” (IC-IPM, 53). The empire of might stands most firmly as an obstacle to the full recognition of the existence of the other. The network of distortions, lies, and illusions constituting the empire of might militates, on the level of politics, against consent, against “the union of contraries.”

The very nature of human will is to assert itself wherever possible; the strong do as they will and the weak suffer what they must. In social and political terms, the weak, the poor, the marginal, for all intents and purposes, cease to exist as persons. Weil observes: “He who has absolutely no belongings of any kind around which social consideration crystallizes does not exist.” To be non-existent in this sense means to be absolutely disregarded, to suffer in silence. Nothing less than supernatural justice can bestow upon such people the sense of their own humanity. “Supernatural justice, supernatural friendship or love,” Weil writes, “are found to be implicit in all human relationships where, without there being an equality of force or of need, there is a search for mutual consent….” This “search for mutual consent” is so outside the normal range of human impulses that it can only be understood as “an imitation of the incomprehensible charity which persuades God to allow us our autonomy” (IC-PD, 177).

Consent to the being of the other is, as we have seen, a form of mediated consent to limit; it is also an imitation of the kenosis of God and is thus an act of renunciation or decreation. Through the Cross we are led into a spirituality of self-limiting rather than self-fulfillment. To be decreated does not mean that we are annihilated but that we are diminished into God, diminished as fragile bodies, as anguished souls and as social beings starved for recognition. We cannot decreate ourselves. It happens. Disappointments and failures, betrayals and inattention, spiritual emptiness in the presence of material abundance, crushed or crashing careers, family members unworthy of our sensitivity and care, sickness and aging in spite of our exercise programs and vitamin treatments, and finally death which does have dominion–all these strip us of our individuality. And we resist but must finally submit to the renunciation of self.

The role of attention

This is where attention comes in. It always involves the renunciation of self and consent to limit. The attention, Weil writes, is creative. But at the moment when it is engaged it is renunciation. Attention always consents to the autonomy of the other. This presupposes denial of oneself. “By denying oneself, one becomes capable under God of establishing someone else by a creative affirmation…One gives oneself in ransom for the other. . . . It is a redemptive act” (WG-F, 158). Attention bestows reality on the other, or rather, through our act of attention, God bestows fullness of being even where the social reality denies it. We find in Weil’s writings an account of justice which pertains not to the way in which people orient their will or predispose themselves to act toward each other, but, first and foremost, to how they see the other, and how they see themselves in relation to the other. If people see a world with themselves at the center, they will not see what is at stake in their relations with others; they will not see limits.

This is why, for Weil, the language of modern political and moral theory was ultimately inadequate: it was grounded in the language of the will. The basic assumption of modern liberal thought is that each individual seeks, by calculation and contrivance, to extend his own claim, to realize his own narrow interests, to self-actualize. This language gives rise to the illusion of being without limits. In the society in which we are living, ‘the rattle of everything that leads to the future” is more deafening and frenetic than ever. It constitutes for us the very matrix of myth and illusion that, for the heroes of the Iliad, took the form of the self-perpetuating violence of war. Accordingly it is a principle of limitlessness that blinds us to the true nature of reality. There is a sense of vertigo in the pace of technological development, expanding markets, the proliferation of new forms of media and advertisement.

The limits of liberalism

Weil thought that the language of “rights” was a prime example of the inadequacy of modern liberal discourse. Liberal theory, particularly in its Lockean form, starts from the conception of a person essentially as an autonomous property holder. The language of “rights” corresponded to this conception. “The notion of rights” Weil contends, “is linked with the notion of sharing out, of exchange, of measured quantity. It has a commercial flavor, essentially evocative of legal claims and arguments” (SWA-HP, 81). This is intrinsically inadequate. The real problem, for her, with the notion of rights is that it does not capture the sense in which a human being is both limited and limit. As a precondition of any kind of political justice, limits must be observed within the social world. Weil writes, “any imaginary extension of these limits is seductive, so there is a seduction in whatever helps us to forget the reality of these obstacles” (SWA-HP, 72). The language of rights ultimately obliges this human desire to obscure the truth of limit.

On the other hand, obligation as a principle in human relationship, and in the larger social world, is grounded “in a reality outside the world, that is to say, outside space and time, outside man’s mental universe, outside any sphere whatsoever that is accessible to human faculties” (SWA-DS, 221). The human longing for good that is “never appeased by any object in this world” corresponds to this transcendent reality. Central to Weil’s critique of rights was the observation that “rights are always found to be related to certain conditions,” whereas “obligations alone remain independent of all conditions” (NFR, 4). Weil’s language of obligations unearths two different aspects of the human experience for which modern political and moral philosophy has no words. The first is the experience of injustice as something more than just the thwarting of one’s will, or the disregarding of one’s legitimate claims, but as something akin to a “sacrilege.” The second is the sense of being bound unconditionally to another in a way that is not simply to be understood in terms of utility. Both of these experiences represent dimensions of the “uncomfortable mystery.” They direct our attention to the truth of limit. The language of rights emerged from the liberal assumption that the essence of a human being is her/his freedom. Weil’s language of obligations, on the other hand, is founded upon an ontology of limit from which it may be deduced that it is in fact a higher “good” for human beings to know that they are limited.

A new language of justice

With the concepts of limit and obligation, Weil invokes a new language of public life that expresses, in the clearest terms, an account of justice that goes far beyond that of modern humanism because it contains within it an answer to the question: to what end? It is the task of language, art, religion, a certain kind of science, and an inspired politics to draw attention, in public terms, to this deeper level of concern. Because good, beauty, and truth are given only in “lightning flashes . . . moments of pure intuition” -(N, 156), a public language of good becomes crucial for us though we may often fail to notice its absence. Good always evokes the language of limitation as the key to our understanding of the beautiful and just.

Lawrence E. Schmidt is Associate Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto (Mississauga). His books include Historical Process and Hermeneutical Method in the Theologies of John Macquarrie, Schubert Ogden and Wolfhart Pannenberg(ICT Press, 1976) and The End of Ethics in A Technological Society with Scott Marratto (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2008). He has also authored numerous scholarly articles on Simone Weil, among others.

The above remarks were presented as a paper at the annual colloquy of the American Weil Society (24 April 2021).

Sources

E. Jane Doering & Ruthann Knechel Johansen, When Fiction and Philosophy Meet: A Conversation with Flannery O’Connor & Simone Weil (Macon, Ga., 2019) (WHP)

O’Connor, Flannery, Mystery and Manners (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1969) (MM)

_______, “A View of the Woods,” in The Complete Stories (New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1969) (TCS).

_______, as cited in Wallace, Bronwen, The Stubborn Particulars of Grace (Toronto: McLelland and Stewart, 1987) (TSPG)

Pétrement, Simone, Simone Weil: A Life (New York: Schocken Books, 1976) (P)

Weil, Simone , Gravity and Grace (New York/London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 2002) (G&G)

_______, “Fragment: Foundation for a New Science” in Science, Necessity, and the Love of God translated by Richard Rees (London: Oxford University Press, 1968) (SN-F)

_______, “The Pythagorean Doctrine,” in Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks, (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1987) (IC-PD)

_______, “The Iliad, Poem of Might,” in Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks, (London and New York: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1957) (IC-IPM)

_______, “Divine Love in Creation,” in Intimations of Christianity Among the Ancient Greeks, (London: Ark Paperbacks, 1987) (IC-DL)

_______, The Need For Roots, (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1952) (NFR )

_______, The Notebooks of Simone Weil (England: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1956) (Arthur Wills trans.), Vols. I & 2 (N)

_______, “Human Personality,” in in Simone Weil: An Anthology, edited with an introduction by Sian Miles (London, Virago Press, 1986) (SWA-HP)

_______, “Draft for a Statement of Human Obligations,” in Simone Weil: An Anthology, edited with an introduction by Sian Miles (London, Virago Press, 1986) (SWA-DS)

_______, “Forms of the Implicit Love of God,” in Waiting for God, (New York; Harper Colophon Editions, 1973) (Emma Craufurd, trans.) (WG-F)

4 Recommendations