Unfinished: On Venice Saved – a Q&A with Silvia Caprioglio Panizza and Philip Wilson

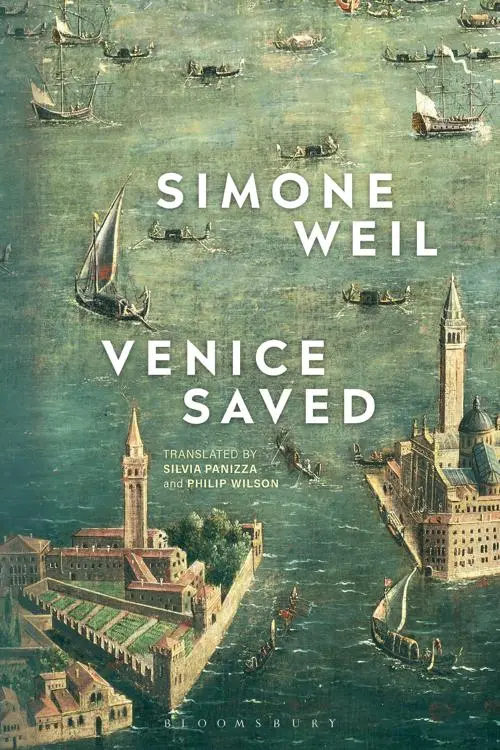

Silvia Caprioglio Panizza and Philip Wilson (interviewed by Ronald Collins)In 2019 yet another one of Simone Weil’s unfinished works, Venice Saved, was resurrected thanks to a new translation by Silvia Caprioglio Panizza (University College Dublin) and Philip Wilson (University of East Anglia). Apart from a bootleg translation that had circulated for some years, Panizza and Wilson were the first to translate Weil’s three-act tragic play into English. They include numerous revealing extracts from Weil’s notebooks that sketch out her ideas about the direction of the uncompleted play. Panizza and Wilson also add commentaries and endnotes to fill in a number of the blanks left open by Weil.

What follows are a series of questions posed by Ronald Collins to Silvia Caprioglio Panizza and Philip Wilson.

Question: You begin your acknowledgments by thanking Davide Rizza. How was he instrumental in this project?

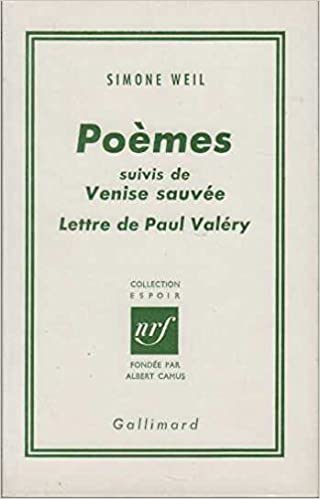

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Davide Rizza teaches philosophy at UEA and, although his research interests focus on the Philosophy of Mathematics, he is conversant with Weil’s work and Weilian scholarship. He came across Venise Sauvée in the Gallimard edition and brought it to our attention. In addition, we had learned a lot about Weil from his Philosophy of Religion lectures and from a Weil reading group that he convened. So you could call him a mediator, to anticipate a point that you make later. In addition, he offered great encouragement at each step of the journey. Translation – in every sense of the word – is something best done with others.

Other Translations

Question: In your book you note that a “translation and adaptation by Richard Rees was broadcast on BBC radio in January of 1957 . . . .” (39) What has become of that audio file? Is it anywhere to be found?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: We were only able to find the record in the BBC archive website and its listing on Radio Times. There we learned, for example, that Jaffier was played by Alec Clunes. But the program is not available to play online. It is possible that there is no recording, but we don’t know for sure.

Question: When you translated Venice Saved did you consult other translations of Weil’s other works such as Arthur Wills’ translation of The Need for Roots to see how similar words or ideas were translated?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: We decided that key terms in the English Weilian vocabulary should remain the same in order to stress the highly philosophical nature of Weil’s literature. One crucial example is ‘malheur,’ which her translators have rendered as ‘affliction’ in order to signify that Weil means more by it than just ‘unhappiness.’ She was depicting a state of complete desolation, so ‘affliction’ was our choice and Jaffier is an ‘afflicted man’ not an ‘unhappy man.’ The lexical space is occupied, and we respect that.

Question: Weil both translated works (e.g. Antigone) and wrote in languages other than French (e.g. English). In other words, she had a real sense of writing for “multilingual eyes,” assuming, that is, she ever gave much thought of her works becoming public.

Venice Saved was translated into Italian by Cristina Campo (a noted translator) in 1987 (Adelphi publishing), which you reference in your bibliography. In 2016 Domenico Canciani and Maria Antonietta Vito also released their edited version (Castelvecchi publishing). Earlier, in 2007, it was translated into Polish by Adam Wodnicki (Austeria Publishing). Did any of those translations and editions influence your own approach to Venice Saved?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: David Constantine once said that when translating Goethe’s Faust – a much-translated work into English – he only ever looked at other renderings after doing his own, in a form of triangulation that allowed him to review what he had done. We followed the same approach by looking at Cristina Campo when we had finished our first draft.

Translating a Philosophical and Theatrical Work

Question: You’re both translators and philosophers. And you bring your respective talents to bear on a work, albeit unfinished, that combines history and philosophy with drama. As translators you do more than present dictionary-based word-for-word literal offerings of Weil’s text – Yandex Translate can do that! Rather, you become sort of mediators. So tell us about how you mediated Weil’s unfinished work.

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: The image of the mediator is very fitting for the translator, who looks two ways – at the source text and at the target text – and becomes a co-author in the process. Mediation involves reacting to the implicatures in Weil’s writing by finding ways to recreate them for the reader in English. All translations are interpretations, which are interpreted again when they are read by new readers in what Walter Benjamin called the continuing life of the text. And interpretation certainly does demand more than competency with a dictionary, as you say. Eliot Weinberger called it a ‘reimagining’ in the wonderful book he co-authored on translation with Octavio Paz, 19 Ways of Looking at Wang Wei(2016). That book also recommends a humility when confronting the source text, which is how we understand mediation. It’s a form of attention.

Question: Permit me to push the mediation point a bit further: how, if at all, were your ideas in offering the book as you did as informed by J.P. Little’s 1979 article, “Society as a Mediator in Simone Weil’s Venise Sauvée” (Modern Language Review, vol. 65, no. 2, 289-305)?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Venice Saved operates on many levels. The ethical, the metaphysical, and the political. These levels are interdependent, but they can be analyzed separately as a matter of emphasis or perspective. Little’s essay, apart from being one of the few analyses of Weil’s play in English, long before it was available in the English language, is a very important contribution for its clear reading of the play, particularly in the political light. Little lucidly shows the similarities between the Spanish conspiracy in the play, the Roman Empire as Weil saw it, and Nazi Germany at the time Weil was writing.

All of these are for Weil manifestations of the Great Beast, the social as a force in itself, which annihilates the individuals and wants to conquer anything outside of itself. Venice, by contrast, is a city, which for Weil means the medium in which individuals can flourish, in contact with their past and their roots—precisely what the Empire aims to eliminate, as the play makes clear. These are all elements that Little rightly brings out, as well as the connection between the tragedy and The Need for Roots (where we also see how the political, ethical, and metaphysical are intertwined).

Question: On a related score: When one pauses and thinks of it, there is a dizzying quality about the task the two of you undertook in offering Venice Saved. First of all, the play derives from a 1674 work, which was then followed by a 1682 adaptation. In both instances, the offerings were partly based on actual historical events. Then there is Weil’s reworking. To add to the complexity of it all, there is the translation of her play, which itself adds an interpretive gloss onto everything. Can you give us some sketch as to how the two of you navigated these interpretive waters? What were your guideposts?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: All texts are inevitably bound up in a network of signification and translation, so we read the historical fiction by the Abbé de Saint-Réal, on which Weil drew, as well as the adaptations of Saint-Réal by Thomas Otway and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, in order to breathe the same dramatic air as Weil, so to speak, working out just what it was about this story that drew readers and writers to it, including this French philosopher. The aim was to translate as informed readers of the text, to steal a phrase from Stanley Fish. At the same time, Weil’s interpretation of the material is very much her own, with the metaphysical dimension, for example, being absent from the other two. As she does with philosophical ideas, Weil also uses literary texts in her own way.

Question: You offer eight pages of Weil’s notes on Venice Saved and later six pages of “translators’ notes.” Both are most informative and even essential to any real understanding of the play. How did the idea emerge? How central was that to your objective?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Weil’s play is historical in two senses. First, it deals with events that happened long ago. Second, it was written for a specific historical context, in which France had fallen to the power of Hitler’s Germany. Therefore, we decided that we should offer a paratext that would enable our readers to become informed readers in their turn because the play has to be read in history if it is ultimately to make sense. We also wrote four introductory chapters: on Weil’s life; on the genesis and purport of the play; on Weil and the tragic; and on our translation. Translators become visible through their paratext.

The material and reflections we have added allowed us to reflect on the significance of the text we have translated, but also to make clear links between the tragedy and Weil’s thought, specifically her metaphysics, her political philosophy, and her ethics. It is in that context that the play makes sense, and while a reader who already knows Weil will of course find more richness in the play itself, we wanted to enable those who are just beginning to approach Weil to also see all the resonance of her literary work. It is not inconceivable, for instance, that someone whose main background and interest in literature will pick up the book, and the paratext offers that reader an entry into Weil’s world from a different door.

We are aware that some literary authors may complain that their art needs no explanation, and indeed is damaged by interpretation. In some cases, that may be true, but we don’t think that’s the case with Weil. First, as you say, the work is unfinished. Second, the tragedy is so much an expression of Weil’s thought, that it is hard for it to stand alone. After all, Weil was probably aware of a certain tendency towards didacticism in herself, as Paul Valéry noticed in her poetry.

The Play and its Origins

Question: Weil’s writing of the play traces back to at least June 1940 in Vichy, France: There in a tiny rented apartment, recuperating from a leg infection and working atop a sleeping bag spread out on a kitchen floor, Weil pondered the plot of the play. Her draft of it was based partly on a 1674 work by the Abbé de Saint-Réal (César Vichard) and partly on historical events. In 1682 Thomas Otway, an English dramatist published Venice Preserved, which was based on the 1674 work. How similar is Weil’s version to its predecessors and in what significant ways does it differ?

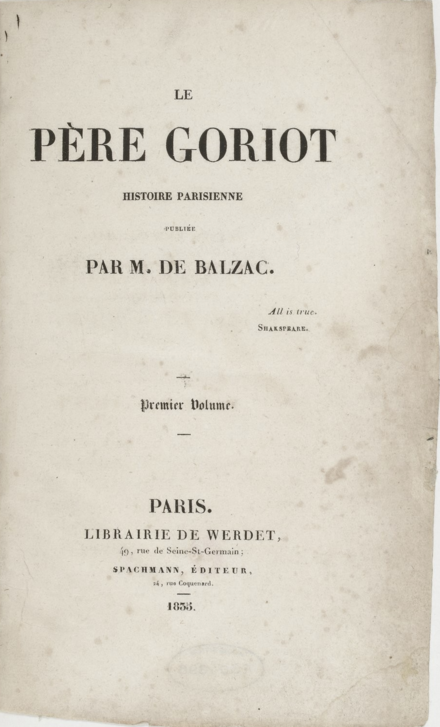

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Otway’s play has always enjoyed great respect in France. In Balzac’s 1835 novel Père Goriot, one character tells another that he has memorized Otway’s Venise Sauvée by heart. Weil knew Otway’s play and took her title from it. We came across this valuable insight in Simone Pétrement’s biography of her friend: for Weil, ‘Otway and others had not understood the nobility of the motive which, according to Saint-Réal, led Jaffier to denounce the plot: pity for the city’. Pétrement’s report gave us a way to interpret the play. What in Saint-Réal is a melodrama and in Otway is a revenge tragedy, becomes something more metaphysical in Weil. She found a story that enabled her to say something that she needed to say through literature, but she is doing something very different from her predecessors. She was also working from Saint-Réal as her source, whereas von Hofmannsthal worked from Otway in his 1905 Das gerettete Venedig(The Saved Venice).

Question: Around this same time Weil was also working on her essay “The Iliad or Poem of Force.” How does that work align, if at all, with Venice Saved?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: That is, like The Need for Roots, another philosophical work that resonates very strongly in Venice Saved, and reading the play with that essay in mind gives the play greater depth. Force is what drives the conspirators in the tragedy, and what drives the Venetians at the end. Like in the Iliad, there is no clear ‘good’ or ‘bad’ side: Weil is showing that force is a factor in human life that is very hard to resist and that it is almost impossible for anyone who possesses it not to exercise it. That’s why it is so important that Jaffier renounces his power voluntarily. And that is why he is implicitly compared to Jesus (their last words are the same), for his renunciation is, in Weil’s view, supernatural.

The idea, which Weil explores in the essay, that force can take hold of anyone, including individuals with moral sensibility and the capacity to care, is shown in the tragedy by the presentation of the Venetians as civilized and refined, yet capable of cruelty and torture; in Pierre, capable of great love and loyalty to Jaffier, who is yet one of the leaders of the conspiracy. In ‘The Iliad or Poem of Force’ Weil talks about a ‘seesaw’ of force, for no one ever holds it securely, and in Venice Saved those who wield it at first are those who suffer from it; and the Venetians, who were so close to being victims that we can already hear their screams, end up being the torturers.

Returning to Jaffier’s end, there’s a third point, made by Weil in “The Iliad or Poem of Force”, that is crucial to understand force and its ethical import: force turns those subject to it into things, mere ‘matter’ as Weil puts it. That’s why it is so easy for, say, the Venetians to hurt even Jaffier, because they no longer see him as a subject. And that view is passed on to the victim, who no longer sees himself as a subject either. That is one way that affliction is reached. But Jaffier, by willing his own fate through renunciation, is able to overcome it.

On Friendship, Heroes and Villains

Question: The concept of friendship in this play is, to say the least, a most complicated one. Given that, what in Weil’s mind constitutes a betrayal of that, and how does that then inform her notion of friendship?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Weil took friendship extremely seriously – well, like everything else – and she wrote some intriguing remarks on it. She took it to be a kind of miracle, something that one is graced with but also that one should exercise. It is ‘not to be sought, not to be dreamed, not to be desired’. These are also exhortations to herself and speak to her own fear of losing that solitude that allowed an intense, honest attention which company dispersed. But in true friendship, a true meeting of souls if you like, solitude and attention can be preserved. Given the great value she placed on friendship, your question is a cogent one: did Jaffier really betray something so important, indeed miraculous?

On the one hand, we can say he only intended to betray Pierre’s plans to make use of force, and did his best to secure his friend’s safety. On the other hand, the Venetians have in their turn betrayed Jaffier, who has to hear the screams of Pierre as he is tortured. Given that Pierre was also unaware of Jaffier’s intentions, dramatic tension arises from the fact that there is no good choice for Jaffier.

That is why we need to remember that saving Venice was not, for him, a choice, but an act of obedience.

Question: Is Jaffier a hero or villain? In one respect, he is a hero for saving Venice. In another respect, he is a villain for first conspiring and then putting into motion the attempted destruction of Venice. What do you think?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Simone Weil was not interested in displaying a problem of ordinary morality. The categories of hero and villain both seem ill-fitting for Jaffier. Weil writes in her notes to Act II, for example: ‘Make it clear that Jaffier’s change of heart is supernatural.’ Before, Jaffier is simply exercising force in the ways that those in power do. After his conversion — and in this context we think this is a more appropriate word than ‘decision’ — he submits to a different kind of power, that of obedience. His vision of Venice shows him the impossibility of destruction and possession. Therefore it is not a ‘good will’ that we are talking about, which is what we attribute to heroes or morally good people. It is something different.

On Innocence & Beauty

Question: The Violetta character is a curious one. Following the murderous male plotting in Act 1, Violetta appears in Act 2 as an innocent: “Oh! I wish it were tomorrow!” is how she makes her appearance (67). How significant is she to the play, both in terms of her gender and her relationship with Jaffier and also with Venice?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: We have to confess that we were both a little irritated by the character of Violetta. Gender portrayal is one of the respects in which Otway’s play seems more successful: his female characters have agency and depth, while Violetta, the main female character in Weil’s play, is a personification of the beauty of Venice. We don’t know whether we are missing something important here, or whether Weil would have worked more on this character had she been able to, but currently, it is difficult not to feel some discomfort when she appears.

Question: No single work of Weil’s better dramatizes the concept of beauty than Venice Saved. Throughout the play beauty wars with evil, and suffering is never too far away. And then there are these words from the lips of Jaffier spoken early on in the play:

“When I see that city so beautiful, so powerful, so peaceful, and when I think that in one night, we, a few obscure men, will become its masters, I believe I’m dreaming” (74).

Later on there is this line from Violetta:

“How lovely on this sea are the rays of the day” (113).

Those are the last lines of the play. So where does that leave us so far as beauty is concerned?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Beauty is certainly one of the keys to this work. We spend some time reflecting on it in Chapter 3 of the book: ‘Weil and the Tragic.’ And the early passage you quote, Jaffier’s words, is very telling of both what is going to happen and the meaning of beauty. Jaffier is indeed a dreamer for thinking of possessing beauty, in a pejorative sense (let’s keep in mind that reality and truth are normative in Weil).

As Weil understands it, beauty invites desire but defies possession. And that’s when desire is transformed into love. So at the beginning, Jaffier already knows that beauty cannot be possessed, in a kind of tragic irony, and his capacity to be affected by beauty prefigures his later conversion. In Waiting on God, Weil discusses beauty as one of the “forms of the implicit love of God”. Beauty is not just aesthetic, it is not an enjoyable pastime for a refined sensibility. It is the most accessible manifestation of the order of the world – an order, for Weil, determined by God. So what may seem superficial – sacrificing everything for a vision of beauty – is instead a manifestation of respect and indeed love for reality as a whole.

Between Gravity and Grace

Question: One senses that Jaffier, the hero of the play, finds himself in a sort of tug-of-war between the natural and the supernatural, between gravity and grace. In that regard, you quote the following passages (51-52) from Weil’s notes on the play:

It is necessary to give form to the sentiment that it is the good that is abnormal. And this is how things are in this world. We do not realize this . . . . Abnormal but possible: this is the good.

Evil should also be shown to be vulgar, monotonous, dismal, and boring.

Things in the form of values are unreal for us. Yet false values also remove reality from perception itself by means of the imagination that envelops it . . . .

In light of that, how is this rending of Jaffier resolved and where, philosophically speaking, does that leave the reader? . . . or is the matter never resolved?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: It’s interesting to read your question through Weil’s notion that God has withdrawn from the universe. In a striking parallel with the work of Isaac Luria, she asserts that it is possible to come across light in the darkness and to achieve a temporary victory from time to time. The saint is an exception, but one that is worth dwelling on. Weil was fascinated by the figure of Prometheus, who sacrificed himself to bring fire to humanity and was cruelly punished by Zeus. She wrote at length about him in the Cahiers and also composed a poem about him. Prometheus and Jaffier are defeated, but their defeat can offer hope to the world. Venice will need saving again and again. (At the time of writing, it seems to be threatened by the rising waters of climate change.)

The Unfinished Life

Question: The work you presented in your translation was an incomplete one since Weil never got around to finishing it. And with all due respect to the great value of your work, the natural tendency when reading the “finished project” is to treat it, at least implicitly, as a completed work with the reader filling in the imaginative gaps. How serious of a problem, if at all, is this? Then again, might it be seen as an invitation for the reader to engage Weil? What say you?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: All literature, whether finished or not, asks readers to fill in the gaps – as Wolfgang Iser states – by attempting to construct the mind of the perceived author. So in this sense, Venice Saved is just an extreme case of a general phenomenon. We see the incomplete state of the text as iconic rather than as problematic: it represents a writer who died in the middle of a world war, whose work was unpublished, whose reception was uncertain.

Venice Saved can now be continued, not completed, in three ways: translation, reading, and performance. It is an event that makes demands on its readers. (Incidentally, we know of two performances that are to take place in 2022, one in English and one in German.) The state of the text also allows the reader a unique insight into Weil’s literary methods – her views on poetry, for example – and is therefore literature in history in a different sense.

Question: In so many ways, Venice Saved seems to touch and test every neural element in our central nervous systems. It does so in persistent back-and-forth, good-and-evil ways. And yet, at the end so much seems, like her life and the play itself, unfinished.

In what larger sense might this be seen as the motif of Weil’s entire life and philosophy? What do you think?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: We think Weil would have cautioned us against seeking completion, aiming for a satisfying and perfect unity. What would completion even look like? The idea that complete unities are human fantasies is one of the thoughts that Iris Murdoch, one of Weil’s keenest readers, took to heart, and which opens her Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals (1992).

Venice saved . . . from what?

Question: From Weil’s perspective, what exactly was saved when Venice was preserved at the play’s end? The new day – that day of “bliss” on the eve of the “feast [that] will fulfill every desire” (113) – came to pass but only at some great cost: betrayal (official and personal), death, and Violetta’s ignorance of all that transpired. Given that, what had Venice really gained other than, to put it rather cynically, a stay of execution? What do you think?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: It matters that the Venetians never knew they were briefly the objects of force because the victims of force are objectified not only in the eyes of those who wield power but also in their own. The inhabitants are preserved, not only physically, but in their being. Then there are two other kinds of preservation. One is the beauty of the city, which has the metaphysical significance that we have talked about. The other is the social order represented by Venice, which stands in opposition to ‘the social’ or the Great Beast, and the possibility of rootedness which the Spanish no longer have. That possibility expresses Weil’s hope in relation to the situation in Europe in the 1940s, and her project in the Need for Roots, as we were saying.

On Translations & Forthcoming Weil Projects

Question: There is a new translation of The Need for Roots forthcoming by Ros Schwartz (Penguin). Generally speaking, what advice might you offer to her as to how to approach the task of translating Weil? What, for example, do those who translate Weil into English need to be especially attentive to?

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Ros Schwarz has a fantastic reputation and we’re really looking forward to reading her work. Venice Saved is largely in verse of course, and we wanted to find a way of representing in English a very different form of writing poetry: an English verse influenced by Weil. Whether that insight is helpful to future translators, we don’t know, but the emergence of new translations must be telling us something about the literary nature of Weil’s writing. She was not just passing on information. She has unique poetics that is clearly seen in her verse play and her poetry but that is also there in the prose. You have to meet her thought halfway and a literary translation will respect that.

Question: You have a new Weil project at hand. What is it and what can you tell us about it?

Might it have had anything to do when you wrote this?

“Her poems are unavailable in English translation, although they clearly mattered to her, as illustrated by her letter to Valéry, by her disappointment that Valéry did not seek a meeting with her to discuss things further and by a letter to her parents in which she writes that it would be ‘nice to produce . . . a few copies of the collection of poems’ . . . .” (47)

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Yes, we are fascinated by the literary Weil, by someone who read widely in French and World Literature and who also needed to turn to literature in order to express what she could not express through more conventional ways of writing philosophy. (Francophone culture of course has a noble tradition of philosopher-authors, from Voltaire to Simone de Beauvoir and beyond.)

The Gallimard edition includes her poems, so we approached Bloomsbury with the project of a companion volume to Venice Saved that would offer the poetic output of Weil. They are bringing the book out next year, we are happy to say. It will offer nine poems as well as some verse extracts from Venice Saved, plus a story written when she was eleven and an essay about a Grimm tale composed while she was preparing for university entrance. Again, we’re writing notes and introductory material. We’re really excited that space allows for a bilingual edition so that the French source texts will face our translations, something that will allow readers with French to encounter what Weil wrote, while all readers will be able to track key terms and compare the shape of source and translation.

The poems are being translated as poems in their own right rather than as prose summaries, out of respect for Weil’s stylistic choice. Poetry mattered to Weil – she wrote a poem about Prometheus, for example, whom she saw as a redeemer-figure, as we said above – and her poetic work deserves an Anglophone audience. Slowly the mosaic is being built up that will enable Weil to be represented in the twenty-first century that has desperate need of her vision.

Collins: Thank you Silvia and Philip for taking the time to answer my questions about Venice Saved and your creative and constrained role in bringing it to life for our English-speaking audiences. And do keep us posted about the release of your next book.

Caprioglio Panizza & Wilson: Thank you for asking such interesting questions that are clearly based on an informed reading of our translation.

Recommended Reading & Viewing

In addition to J.P. Little’s essay mentioned above, some other worthwhile commentaries on Venice Saved include:

- Jacques Cabaud, Simone Weil: A Fellowship in Love (New York: Channel Press, 1964), 197-202.

- Yoon Sook Cha, Decreation and the Ethical Bind (New York: Notre Dame, IN: Fordham University Press, 2017), 65-102.

- E. Jane Doering, Simone Weil and the Specter of Self-Perpetuating Force (University of Notre Dame Press, 2010), 142-150.

- Gabriella Fiori, Simone Weil: An Intellectual Biography (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press 1989), 184-188.

- Simone Weil Bibliography: University of Calgary (listing commentaries in other languages)

- Philip Wilson, “Literary Translation: an Overview,” Turjuman Project, YouTube (Sept. 4, 2020)