From Italy: Translation as a Metaxù and a Play as an “Evocation” of Simone’s Life — An Interview with Maura Del Serra

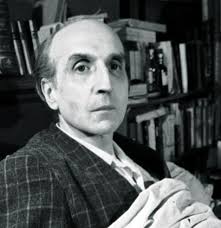

Michela DianettiMaura Del Serra, former Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Florence, has published collections of poems, plays, essays, and critical works on multiple authors as well as several translations. She translated Simone Weil’s poems (Pistoia, C.R.T., 2000), and wrote La fonte ardente. Due atti per Simone Weil (published in 1991 by the journal Hystrio and staged in Florence in 1992 and in France in 2017), based on the life and thought of Simone Weil.

In 2021 she published with Le lettere a new translation of L’ enracinement with the title Il radicamento. This is the first new Italian translation of Weil’s work after the original translation by Franco Fortini, which came out in 1954 with the title La prima radice.

In what follows she tells us about her new translation of L’ enracinement, her relationship with Simone Weil, the process of translation in general, and her exquisite play on Weil.

This interview was conducted by Michela Dianetti. Some of the questions below were made in collaboration with master’s students Annamaria Totagiancaspro and Ilaria Vrenna during Dianetti’s seminar on ‘Attention & Translation’ within the module ‘Advanced Language Skills in Italian’ at the University of Galway, Ireland. Annamaria Totagiancaspro and Ilaria Vrenna translated this interview from Italian into English, under the supervision of Michela Dianetti.

The Interview

Question 1: Let us start with the title itself — the book known in English as The Need for Roots. Franco Fortini’s first translation chose to title the book ‘La prima radice’. Can you tell us about your choice of keeping the literary translation ‘Il radicamento’? And more in general, how do you think your translation differs from his?

Del Serra: Mine was a choice of conservative philology, namely of faithfulness to Simone’s text. There are two reasons for that: the first is that the title “Il Radicamento” is also the title of the third part of the book, which is why Camus chose it as the title of the first edition in 1947. Similarly, the second reason is that the concept of “radicamento” (rootedness) is central and dialectically progressive in Weil’s book, which goes through the opposite and different types of “sradicamento” (uprootedness). On the other hand, Fortini’s title wasn’t as dynamic, but instead rather static, abstract and absolutizing. It created this sort of Old-Catholic aura, which was surely consistent with the historical period when Simone was “discovered” in Italy, in the 1950s. However, it doesn’t really conform to the progressive Weltanschaung of the book, which is both a testamentary diagnosis, and a prognosis full of prophetic hope for the possible historical and spiritual rebirth of post-war Europe.

Therefore, my translation differs from Fortini’s not only because of the obvious lexical and linguistic “modernization” – I eliminated obsolescence and corrected some mistakes. I also integrated the last part of the text (that hadn’t been found yet at Fortini’s time), which still preserves, rightfully, the original incompleteness of the text, but without ending it abruptly. Furthermore, I added an equally necessary introduction and a body of clarifying notes that can be useful to contemporary Italian readers. Fortini’s pioneering translation was lacking both the introduction and the notes.

Question 2: While translating the text, did you consult Fortini’s or other translations in other languages?

Del Serra: I only consulted Fortini’s version, and only as an external reference to the text. I deeply focused my attention (specifically as Weil intends it, as “listening/meditating/actively contemplating”) on the original French text, to create a “descant” as faithful and similar as possible to the original “voice/chant”. I didn’t want the original text to pass through an overly diffracted and distracting “chamber of mirrors” through other languages, which would have distanced me from the original.

Question 3: L’enracinement is a complex text; no doubt, it asks for a skilled and dedicated translator like yourself. When Weil was writing L’enracinement, she was working for “France Libre” and her job was to select what they received from the resistance committees and then pass that on with annotations to De Gaulle. Eventually, while doing that, she put together thoughts and responses to what she received and managed to envision, in what would then become L’enracinement, what she saw as the necessary foundations of post-war Europe.

Therefore, since the work was published posthumously, and Weil didn’t have the chance to revise it before it was published, there are various rough and difficult sections in the text. How did you deal with them? Did you leave or clarify them?

Del Serra: As I mentioned in response to your first question, when I translate, my principle focus is constantly that which in art history is called “conservative restoration”, which is a “re-creative” faithfulness to the text, wherever it’s most needed, and as much as it’s needed, which is especially in the roughest and most incomplete passages of the book. I tried to keep these passages as they were in the original, clarifying them just enough, but without altering them excessively.

It’s a complex and delicate job of balance, led both by experience and empathy, by the mens cordis (mind of the heart), which searches for the most balanced harmony with the author’s voice – which in Simone’s case is absolutely “deep and clear”. Here I’m paraphrasing Nietzsche when he said “Whoever knows he is deep tries to be clear”, although Simone was never particularly fond of him, because of his apparent hybris, and his Germanic lack of geometrie. However, in Dante’s Paradiso, the source of this twofold quality is the “deep and clear subsistence” of the divine light, which can be attributed as well to its great human interpreters.

Question 4: In the first sentence of the book, you use the word “dovere” and not “obbligo”, unlike Fortini. Could you tell us why?

Del Serra: I chose the word “dovere”, instead of “obbligo”, for its greater affinity with the original “devoir”. It also has a greater semantic range of meaning in an ethical sense. In fact, for an Italian reader, it’s associated with the socio-philosophical Mazzinian tradition of “i doveri dell’uomo” (the duties of man). The concept of ‘duty’ is parallel to the concept of ‘right’ which instead was the ideological banner spread throughout Europe by the Enlightenment and the French Revolution. Instead, the word “obbligo” in Italian doesn’t have this same abundance of historical, ethical, and pedagogical connotations—which date back to Kant’s “moral law within me” (well present in Weil’s education)—and it feels much more limiting and restrictive, nearly punitive.

Question 5: Ros Schwartz, the translator of the new English edition of The Need for Roots, holds that not being a Weil scholar was a plus for her because she had to understand Weil’s ideas herself and this made her realize what could be hard to understand for a lay audience and what was worth glossing (See her interview in Attention). How much of your work is, instead, guided by your high understanding of her philosophy?

Del Serra: I don’t consider myself a Weil scholar. Instead, I think of myself as her ideal disciple (since I was young). Being first and foremost a poet, I think and feel with cognitive empathy (Einfühlung, in German). Therefore, my “high understanding” of Weil’s philosophy was mainly born from that devoted admiration that we feel towards the personalities of our spiritual teachers, rather than from an analytical study of her main themes. Clearly, some kind of analytical study was still a requirement and implication in my work as a reader, author, and translator. All of this owes so much to Weil’s imprinting—especially to the mystical and philosophical eastern sources, such as the Bhagavad Gita, which I had already encountered on my own when I was about twenty years old.

Question 6: Can you tell us a bit more about your encounter with Weil’s work? How did you come across Weil’s work and what struck you the most?

Del Serra: My encounter with Simone’s work dates back to the 1970s and precisely 1972, the year of my graduation. In that period, the wealth of Weilian works (yet still restricted to the elite) started in Italy through translations now greatly popular: “Attesa di Dio” (Waiting for God) published in 1972 in the Italian version of Orsola Nemi and with the empathic introduction by Cristina Campo who signed it under the mysterious pseudonym of Benedetto P. D’Angelo (later I met Cristina personally in Rome in 1976, during a visit, and we kept in touch epistolary until her death).

In 1974 I read with great admiration the volume “La Grecia e le intuizioni precristiane” (Greece and Pre-christian intuitions) (by Rusconi), which collected essays from “La Source Greque” and “Les Intuitions Pré-chrétiennes” (“The Iliad or the poem of force,” “God in Plato” and other minor writings), translated by Campo and Margherita Pieracci Harwell (a dear friend of Campo’s, who also became a dear friend to me from the 1990s). Simone Weil became ultimately crucial to me in the 80s when the publishing house Adelphi published four volumes of the “Cahiers” in the praiseworthy translation by Giancarlo Gaeta (from where I got many details, even psychological and stylistic, for La Fonte Ardente – The Ardent Spring).

Gradually, I read other works by Weil both in translation and in the original, the nine poems of the 1968 French Edition which collected them together with “Venise Sauvée.” Thereafter, I felt the urgency and the need to translate her poems into Italian. With gratitude, I read the detailed and meticulous biography by Simone Pétrement (translated into Italian many years later) and then another one (a little bit miscellaneous) by Gabriella Fiori (which today could be defined as a biopic in cinematographic terms) and various numbers of the “Cahiers Simone Weil.”

The splendid strength and the mystic-metaphysical impulse of Weil’s “radical” thought (also in the etymological sense) is what struck me the most about Weil’s figure and her works. Her thought can connect classical and modern sources of Western culture with the traditions of Eastern thought, conjugating contemplative thought and revolutionary action, utopia and history, creature pietas and clear political-social analysis, and blend them not only in the sense of ideal androgyny like in the case of Woolf, but rather in a very high holistic feeling. That helped me a lot to develop through time my spiritual and juvenile uncertainties and my still abstract and literary feelings. These are flaws that I consider still present in the “effusive” and theatrically redundant structure of La fonte ardente.

“Elective Affinities”: Translating Other Writers

Question 7: What about the other “affinità elettive” (“elective affinities”) of which you spoke in other interviews? You said that the authors you translated (Shakespeare, Herbert, Proust, Woolf, Thompson, Mansfield, Djuna Barnes, and Weil), were chosen based on your connection to them, almost as if the translator and the author are like two musical instruments that need to be tuned in the same key. What can you tell us about your relationship with the authors you translate?

Del Serra: Without a doubt, and pervasively, all my translations have originated based on my “elective affinity”— the Goethean Wahlwerwandschaft — with the authors. I wouldn’t say I chose them, but rather that they chose and “called” me, like some Pirandello characters in search of an author. Or, as the poet Margherita Guidacci, very dear to me, said: those who “wanted me” as a necessary accompaniment/discant to their voice, just like two musical instruments in harmony. However, translation always remains a sort of imperfect “golem” of the original—I always keep in mind Dante’s warning, when in The Convivio he claims that translating is impossible, or at least translating poetry, the one which is “per legame musaico armonizzata” (harmonized musically). The relationship with my “electors” has obviously changed with time: at first, it was determined by the appeal or rather by the challenge to fill a historical and poetical gap; that was the case for my first translation, Ballate ebraiche e altre poesie by Else Lasker-Schüler, published in 1985. At the time, there were only some older versions dating back twenty years—literally but not lyrically adequate, edited by Giuliano Baioni—and a few chosen poems in the anthologies of German expressionist poetry.

When I translated Shakespeare and Proust instead, it was the publishing house that asked me to do it, but I felt equally honored and privileged to confront two opposite “beacons” of Western literature, whom I have always loved since secondary school. In Proust’s case, Recherche was a real teenage love for me back in 1964—then integrated with all his other works—which left a deep mark on me. In Shakespeare’s case, his influence on me was more gradual, and initially I focused on the Sonnets—I still believe it’s impossible to properly translate them into Italian, despite the various versions in prose or poetry. Translating Shakespeare was as hard as exciting, as I attempted to restore the Bard’s verses in similar blank verses, and in strophic form for the Songs included in the plays and intended for singing on stage.

Similarly, an element of stylistic and internal “loving” challenge—basically a homage— was also present, although in different terms, in the “elective” translations of George Herbert and of the neo-Elizabethan Francis Thompson. There was no previous Italian anthology edition, and I felt like they were “calling me” with the sacred highness, and the lively, eloquent and powerful wit of their voice/song. Actually, I discovered Herbert through Simone’s loving fondness for his moving poem Love, which she would recite as a mantra in her last years.

Likewise, in Katherine Mansfield’s case, when in the 1980s I read the Italian translations of the corpus of her extraordinary and original short stories, I felt like I was “called” to do her (stylistic) justice. That’s because in Italian her stories were published by Adelphi in five small volumes translated by different translators, which made the collection unavoidably uneven and extremely heterogeneous. It was, for me, an energetic and passionate work of synchronization, and it led me to the production of the monologue Kass, and the translation of Katherine’s poetry corpus, never attempted or achieved before.

Even harder, but equally exciting, was the tripartite work on Virginia Woolf. I felt particularly connected with her when translating The Waves (Le Onde in Italian), precisely for its intense lyrical prose. Also, rather than a novel, it resembles a musical score for six voices/characters/instruments. In particular, I still find it impossible to reproduce the rhythmic beat of the almost Wagnerian Leitmotiv of “The waves broke on the shore”, which depicts the fatal and cyclical passing of time as a flow of consciousness. Due to an absolute lack of correspondence in Italian, I was forced to translate it with the trivial and verbose “Le onde si frangevano sulla spiaggia”. These are the Gordian knots of every translation, knots that are impossible to either untie or cut off. In Woolf’s case, I used the cor mentis (heart of the mind) more than the mens cordis(mind of the heart), given her sharp and analytical semantic precision. In 1994 I received the “Betocchi” award for the translation of the triptych The Waves, Orlando, A Room of One’s Own, and I was very proud that they stressed the diversity and peculiarity of the lexical accent I had used for each volume.

In Djuna Barnes’ case (she’s even sharper than Woolf), the choice of creating an anthological translation of her poems came from the fact that I had to abandon the “heroic” attempt to translate The Antiphon, her drama of neo-Elizabethan overtones. Its style is so difficult and feverish that it gave me an actual physical fever when I was looking for an equivalent in Italian. I felt rejected by the author and ended up abandoning the project after only a few pages—besides, there is a translation of the drama by Élemire Zolla and Cristina Campo (Adelphi), but it was never published because they thought it was still “to be reviewed”, which never happened. Djuna, instead, “accepted” my versions of her poems, but only partly, given that in the audacious edition, also containing Barnes’ first chronological biography, she mysteriously “skipped” the index of the same poems!

I found elective affinity also with some living poets (at the time, or still today) such as Michael Hamburger (in 1999 I developed the first poetic anthology in Italian) and André Ughetto—my talented French translator— (similarly in 2016 I produced an anthological edition of Poesie in Italian). With Ughetto’s translation and direction, La Fontaine ardente debuted in August 2017 in Isle-sur-la Sorgue. The last living author I translated, in 2023, was the American poet and narrator Robert Kelly, well known in the USA, but almost unknown in Italy. His poem The Cup (La Coppa), relates to the transcendentalist tradition, but also syncretistic, Zen, mythical and mystical sources. This translation represented a unique linguistic opportunity, for its “beat” generational rhythm of lyrical prose or of “on the road” pilgrimage, dense with allusions and subtexts, very hard to recreate in such a melodic and polysyllabic language like Italian. But Kelly was enthusiastic about this “gift”, and this will always be the best reward for a translator.

Back to L’enracinement

Question 8: Back to L’enracinement. Are there sections that you found particularly challenging? What do you see as the greatest challenges to translating Weil in general?

Del Serra: The most challenging part of L’enrancinement was the third and last part (the homonymous one), precisely because of the intensity of its pathos, and because of its “reconstructive” vision of the structure and the ethical-spiritual values of post-war Europe and humanity in general. It is an élan (impulse) that is both mystical and lucidly rational at the same time, expressed with the unique accuracy of a prognosis, a “prophetic” clarté (clarity) that can’t be betrayed or emphasized.

In general, however, the biggest challenge of translating Weil, as previously mentioned, was the translation of her poems. In the first three poems, the influence on Weil of the poet Paul Valéry is still visible. Instead, I find the others like La mer, Necessité, Les astres, La porte, and the extraordinary and arcane Prologue – which I always found very moving, and which I inserted (translated) in La fonte ardente as the only possible ending – as extremely intense in their evocative rhythm. I’m mainly referring to La mer, Necessité, Les astres, La porte, and the extraordinary and arcane Prologue, which I always found very moving, and which I inserted (translated) in La fonte ardente as the only possible ending.

Question 9: When Weil does her own translations, say of Greek, do you compare that against the original work she translated?

Del Serra: Yes, the comparison is instinctive and natural, maybe implicit for me, given that the Ancient Greek language is the common source and the supporting koinè of the Western civilization, very dear to me as to Simone. But for her, it was a daily practice, given her specific philosophical education which recalled her constantly “à rebours”, to the classical and pre-Christian origins of our thought, especially Platonic and Stoic. I find that her translations and quotations (dispersed in the two respective essays “God in Plato” and then fragmentally in the Notebooks) are very beautiful, lucid and crystal clear, a lovingly faithful mirror both intimate and objective. The Ancient Greek was her ars magna, her alchimie du verbe, today we would say her etymological ecology, the house, the domus aurea of her rootedness in the Being and in the world.

Question 10: One could argue that Weil’s use of the word homme (man) as a generic term for “human being” is problematic for a contemporary audience that appreciates non-discriminatory language. How did you face the question about either being faithful to the author or meeting the new generations’ expectations?

Thoughts on Translating “Homme”

Del Serra: In Simone, the noun “homme” has undoubtedly the general and universal sense of the “human being” (like the German Mensch and the Gitano Rom), this according to the linguistic male-dominated tradition that goes from the classical world to the first part of the 20th century. After all, it is well-known that Simone lived a conflicted relationship with her own femininity and also because of her immeasurable admiration for her brother André. In fact, in her juvenile letters to her parents, she signed herself as “votre fils numéro 2” (analogically, the Prologue is thought and expressed in the masculine form, according to the Greek-classical and Socratic tradition of the relation between Teacher and Disciple).

Equally known is Simone’s conflicted and antithetical position regarding her homonymous and psychological feminist “double”, Simone De Beauvoir, a conflict that I represented as a confrontation in La fonte ardente. Therefore, I think that the “philological” faithfulness to the linguistic auto-representation of Simone is an essential and absolute priority over the non-discriminatory expectations of the contemporary audience.

Simone’s linguistic choices, as those of any author, should be traced back and related to the Zeitgeist of their age, with a respectful accuracy by the translator, without adapting to the more or less common expectations of the readership and contemporary feminists’ “cancel culture”. I believe that Weil’s readers can take on this historical-philological projection that I adopted in order to translate her, and that they can become translators themselves, as requested by their being lectores in fabula.

Question 11: You once said, in relation to being a translator and a woman, that ‘these two nouns ultimately form only one, since the feminine is by its essence an element of mediation and therefore of translation’ (In AA.VV., Armonie di donna, Pistoia, Banca di Credito Cooperativo, 1995 – here). Can you tell us a bit more?

Del Serra: I meant that the feminine is in her nature holistic, sympathetic, fluidly “interconnected” with several levels of existence and natural, human, and cultural experience — the well-known empathy, and the ability for nourishment and care. The feminine “I care” of the woman makes her a “pontifex”, a metaxú, to use a substantivized adverb dear to Simone and reclaimed by Cristina Campo “in medio coeli”. The woman is a “traduttrice elettiva” (an elective translator) both in the linguistic sense and in the psychological and spiritual ones. This element of intuitive connection (in the etymological sense, thus non-sentimental) between the height and the depth of experience, between the attention to daily life signs and the ones of the “great systems” brings the woman very close to the nature of poetic, artistic, mystic and scientific experience. This relates to what Jung said in his later years “I don’t need to believe, I know.” I mean that the esprit – feminine mind – is an attentive esprit de finesse, nourished and not contradicted by the esprit de geometrie, which favors, as also in my case, the suffered synesthetic ability to “feel the incense that burns” as a Japanese Zen Quote says, and therefore to translate kindred authors. The poet, as Umberto Saba said, is at the same time man and woman, Petrarca and Laura.

Translating as Mediating

Question 12: You mentioned the Weilian word ‘metaxù’. Can you tell us a bit more about your poetic vision of translation as a bridge between languages, like poetry is a bridge between the visible and the invisible? And what kind of bridges did you build from within L’enracinement from French into Italian?

Del Serra: Translating is mediating. This is implicit in the etymology of “translate”: trans-ducere, to ferry an author from an inner land into another, creating a sort of third ideal author. There is much mystery in translating, as in every conception and generative process. That is the result, as Plato said of eros, of poros and penìa, abundance and deprivation in its impulse, in its desirous gift that is also a deep need and deep identification of the self into the Other.

I believe that the judgment on the kinds of bridges or the “plural bridge” that I built, or at least tried to build, translating “L’enracinement”, is up to the Italian lector in fabula rather than me. I wish I laid a lasting bridge, linguistically faithful without being a hasty “calque” of the original. Using the oxymoron that every reliable translator needs, I hope my translation is one “faithfully unfaithful” and also useful to the Italian reader thanks to the mentioned corpus of clarifying footnotes, which are about historical events, and historical, philosophical, and literary figures mentioned by Weil in the text, and also essential introduction. I hope to have built a bridge where the Italian reader can live while building others, in harmony with Simone’s thoughts and experience. Her life and philosophy were, and still are today, a necessary bridge for Europe and the contemporary West, which still suffer from discord and violence (personified in the goddess Eris by the Greeks). This brings us back to the concept of “force” and to her essay on the Iliad and to the antithesis between La pesantêur et la grâce (title mistakenly translated and still not corrected in Italian as L’ombra e la grazia – Shadow and Grace – instead of La gravità e la grazia – Gravity and Grace).

Advice to Students

Question 13: Lastly on translation, do you have any advice for the students who participated in this interview, and who want to pursue a career as a translator?

Del Serra: My advice can only be this: study and listen deeply to the authors you propose to translate. Study their life, their experiences, their specific language or idiolect within their native language, their inner music with its personal, historical, and spiritual consonances and dissonances. Be faithful, with the necessary — and only apparent — “infidelities”, by which I mean creative adaptations on your part, to the extent that they are required by the text of the authors you choose. That is, let yourself be chosen and called by the authors who “want” you and call you, renouncing the others who might fascinate you but who you do not “feel”, or who are not congenial to you in your native language and in the language of your soul. But if some translation is commissioned for you, don’t refuse to put yourself to the test anyway.

I thank you and hug you all as future pontifices, together with your talented and passionate tutor Michela Dianetti.

The Play’s the Thing

Michela Dianetti: La fonte ardente is a play written in 1985 by Del Serra that came out in 1991; it was staged in Florence at “Teatro di Rifredi”.

While Liliana Cavani, in her script for a movie on Weil, Lettere dall’interno (see my Attention interview with her here), represented a more political Weil, one who gave up teaching to work in the factory, you chose to represent her life from the controversial point of her death. It reminded me of the way Gabriella Fiori decided to start her biography (see Attention here, in particular, Jane Doering’s question).

In La fonte ardente we see the woman, and the philosopher, and especially the impossibility of fully understanding her way and the simultaneous magnetic attraction that her life and thought have on us readers. In the play, we see Weil in conversation with multiple characters and we see both the impossibility and the attraction shine in her relationships with each of them — namely, her mother Selma, her teacher Alain, her friend Albertine, and figures such as Bataille, Daumal, De Beauvoir, Trotsky, and Roncalli, etc.

Question 14: When did you start to think about a play on Weil? What was that pushed you to write a play about her?

Del Serra: As already mentioned, La fonte ardente was my very first script for theatre, after decades of poetic and essay writing. This was also about the same time when I started working as a translator. But the decision didn’t come from my first encounter with Simone and her work (in the 1970s and early 1980s), although this was a time when I read a great number of biographies and studies dedicated to her. It wasn’t like I had this thought or made a decision to dramaturgically “structure” my passionate discovery of her, throwing in everything I knew and loved about her (to the point that I would strongly identify with her). Instead, the only appropriate word to describe what happened is the very romantic yet irreplaceable concept of “inspiration”, or in a more sacral and classic way, it was an “epiphany”.

One day in 1985, while I was on a bus to Florence to give a lecture at the University, the two characters of the doctor and the nurse of the Ashford Sanatory literally appeared to me, and I mentally heard him reciting the first verse: “Buongiorno cara Jennifer, come va stamattina?/E la nostra paziente, quell’apostola esausta/dell’autodistruzione, ha superato la crisi?” (Good morning dear Jennifer, how goes it today?/And our patient, that exhausted apostle of self-destruction, did she get through the seizure?) — and she replied melancholic: “No dottore, alle quattro di stamattina è morta” (No, doctor, she died this morning at 4am), and so on. At that point, I only needed to write down the incipit, and then, as soon as possible, I would’ve continued listening to the scene taking shape, almost magically. I was obviously still using my intellect when building the scenes, but as if under dictation, always guided by what Dante called the “intelletto d’amore” (intelligence of love), which “notices” and writes down what it communicates, it “dictates within”.

A few days later I was confined to bed, and I kept writing even with a high fever for a few days, with all the books scattered on the bed. I worked with a sort of enthusiasm or creative rapture. It was a very long and complex, but also exciting translation, or rather an orchestration of figures, of voices turned into characters with their historical and inner world recreated around and through me — person, soul, mind, and the converging experience between poetry, intellectual life, and daily life. There was also the projection of the civil history of Europe and Italy in the 1980s, which were still the “Years of Lead” and of ideological crisis, not too dissimilar from Simone’s in the 1930s and 1940s. I remember that, apart from my husband, I only had the poet Mario Luzi reading the manuscript. He was a sort of fatherly figure for me, and his comment (to my surprise) was: “Good job! I didn’t think you were capable of this.”

Dialectical Sides of Weil’s Evolution

Question 15: Your knowledge of Weil’s philosophy is vast; you manage to make her philosophy shine from within the narration of her life relationships. Why did you choose to recount her through these specific relationships? Why Bataille, why Trotsky, and Roncalli, for instance?

Del Serra: I wouldn’t say “narration”, but rather “evocation” of Simone’s life and pivotal meetings, each of which represents historically and symbolically a dialectical side of her evolution and her personality. This way, besides the “narrative voice” of the mother Selma (who was for the rest of her life the loyal keeper and archivist of her daughter’s work), it was natural and nearly automatic for me to introduce Alain and De Beauvoir for the years of scholastic apprenticeship, representing respectively the father-teacher figure and the “shadow” or “reverse” of Simone.

Then Bataille was like an incarnation of the maudit surrealism (that Simone hated), based on the cult of the subconscious; Trotsky was the “archetype” of the revolutionary Russian soul and the ambivalence between power and persecuted exile, which is Simone’s own ambivalence towards politics, and eventually her disappointed abandonment of militant union activism.

Bousquet and Daumal represent the mystical and esoteric side of surrealism—with the pagan charm of Bousquet’s confining disability, and with Daumal’s premature and deadly illness, of whom I made a sort of male paredroof Simone. Through him, she discovered Eastern thought. Also, I slightly romanticized the loyal friend Albertine, making her Bousquet’s woman and symbol of devoted psychophysical care. As for Roncalli—whose innovative presence in the Catholic Church had a huge impact on me when I was a teenager — when he was the Apostolic Nuncio in Paris in the 1940s, he read part of Simone’s work, admitting and exclaiming: “Oh yes, I love this soul!”. His final meeting with Selma in the closing part of my play felt equally natural (it didn’t happen historically, but it is ideally real), since he was the perfect recipient to introduce the Prologo.

Question 16: The episode with Simone De Beauvoir, also recounted by De Beauvoir herself and Simone Pétrement, is always the most informative, I believe, if one wants to get a hint of Weil’s personality in a nutshell. Here is an extract from the play, where you present Weil in conversation with De Beauvoir:

SIMONE:

Non è facile, è vero,

essere nata donna, avere corpo di luna

e amare il sole. Lo so. Ma so anche

che il desiderio del bene è già il bene,

che si diventa quello che si ama: e mi sembra

che coi falsi valori tu getti via la stessa

radice del valore, l’invisibile patto

fra lo spirito e il mondo, fra il corpo e le sue membra,

fra verità e bellezza.

SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR:

Ma dove e come vivi?

Sei davvero “indigesta”, me l’avevano detto.

{Translation}

It’s not easy, it’s true,

To be born a woman, with a moon-body

And to love the sun. I know. But I also know

That to desire the good is already the good,

That we become what we love: and it seems to me

That with false values you throw away

The root of value itself, the invisible pact

Between the mind and the universe, between the body and its limbs,

Between truth and beauty.

SIMONE DE BEAUVOIR:

What planet are you on?

You are really “indigestible”, they warned me.]

Question 17: Do you want to add something to this passage for us?

Del Serra: De Beauvoir’s proud and “superhumanistic” feminism and her ideological elitism of bourgeois origin prevent her from empathetically “seeing” beyond her own libertarianism and understanding the concrete problems of the people (” I can see you’ve never been hungry” says Simone). De Beauvoir’s problem was and still represents that of the entire European “gauche” of the twentieth century (and beyond), the ideological and divisive abstractness also in her very oppositional feminist thought. Instead, the “indigestible” Simone offers directly her whole person, working in the factory and teaching as an apostle of the lived thought, and as a direct consciousness of the identity of the Other beyond the ego. This is an inner process that is difficult to carry out in any historical time and filled with impossibilia generated by self-defense and the incomprehension of others, which obviously made her come across as “imbuvable” due to her ethical and spiritual, stoically revolutionary, rigor which this process required.

Renewed Interest in Weil’s Work

Question 18: As you said, Weil was often ‘indigesta’ both to her friends and to her readers. Nonetheless, her work continues to be translated, scholarship keeps being formulated, and people keep getting inspired by her and her philosophy. Do you think we are “understanding” her more than before? Now that some time has passed, and that, as she would have it, we’ve placed “distance” between us and her thought” Or maybe is it that our times are dangerously resembling hers and therefore we inevitably gravitate towards the richness of hope (that ‘fonte ardente’) that is her philosophy?

Del Serra: From a historical-biographical and documentary point of view, certainly today the knowledge and study of Simone’s work (almost entirely posthumous) have grown and taken root in the West. If not yet among the general public, more notice is given to her person – often to her “character”, the subject of some films starting from the 1990s – and to her work which extends from her historical time into ours and in a universal sense goes beyond it.

The historical distance, and even more so the recent “spectacularizing” and commodifying globalization of virtual society, risk making her a fake, an elitist one, a “radicalizing” or utopian myth, the absolute opposite of what she felt she was. Instead, hers was a search and a universal prayer on the move, supported by a deep love for knowledge and all humanity, with its violence, misfortunes and pesanteûrs.

In fact, Weil’s was a “hopeless faith”, which allowed her what the ecclesiastical religious called “the discernment of spirits”, that is, the ability to clearly distinguish good from evil, the illusory and pleasant dream from the “hard and wrinkled” reality, as she defined it, with the same “heretical” concreteness typical of mystics. This prevented her both from accepting baptism and from being accepted and canonized by both Jewish and Catholic orthodoxy, perhaps making her a luminous outsider forever. In this extreme sense, we do not know her better today, indeed the constant noise, the media, and the consequent disaffection to meditative reading are greater obstacles than in her time, even if the circles of scholars and enthusiasts can spread and communicate more rapidly with each other, thanks also to the reliable presence of the Weil complete works published by Gallimard.

Question 19: I’d like to conclude by quoting another passage from your La fonte ardente that might sum up all we discussed until here.

SIMONE:

No, non mi sono mai creduta in missione.

Sbagli se credi questo. Ho solamente cercato

di liberare il me dall’io, e di farne

un noi di forza e di sostanza, e offrirlo

come arma minima a chi non ha lingua

per pensarsi soggetto della storia. Non spero,

ma ho fede in questo: è la radice stessa

della rivoluzione: conoscenza unitaria

delle parole e delle cose: fare

parole e dire cose, con la mano e la mente

fuse, senza più il muro fra chi pensa e chi esegue,

quel muro di oppressione e d’illusione che porta

alla rovina l’Occidente stesso.

{Translation}

No, I’ve never thought of myself as on a mission.

You are wrong if you think this. I only tried

To free myself from the I, and to make of it

A “we” of strength and substance, and to offer it

As a minimal weapon to those without voice

To think of themselves as subjects of history. I don’t hope,

But I have faith in this: it is the root itself

Of revolution: unified knowledge

Of words and things: making

words and saying things, with hand and mind

Merged, with no more a wall dividing those who think and those who execute,

That wall of oppression and illusion that leads

The West to its ruin.

Question 20: I hope that this brilliant and beautiful play could see the light again on stage, and hopefully, one day be translated into English and performed to be enjoyed by a wider audience.

Del Serra: I would like to close with Simone’s (and mine) anti-narcissistic and empathic hope contained in the last quoted passage of La fonte ardente: to unite thought and action in “saying things” and “making words” that awaken the conscience and the individual and collective responsibility, the “we” and the “you” antithetical to the “I” today which is more dominant and aggressive than ever in individuals and nations. To testify as much as we can against the flatly narcotizing doxa and in favor of beauty and of alètheia, the truth within and above us, today much denied and feared in favor of the lie and the force that oppresses above all those “without voice”, that is, those without spiritual and social rights. It is important that those of us who “have the word” use it with creative and “fighting” fidelity, as a sword, shield, and gift together, remembering that in Greek “poiein logon“, literally “making the word” also means “giving the word” to someone and being aware of its testimonial power, so hindered by the false dominant powers.

I join Michela’s hope for La fonte ardente to find, after the French one, an adequate translation, perhaps by a poet, and to be staged in English (hopefully by a translator who respects its metric and stylistic texture) re-offering Simone’s thought and life also to the vast English-speaking audience, which has now become an international koinè, a bridge language like Greek and Latin once were. Simone, who loved the richness of all these languages, and also of Italian, as much as that of her mother tongue, will be present, and I with her, in each of them and in any other that welcomes her.

Michela Dianetti is the Italy correspondent for Attention.

6 Recommendations