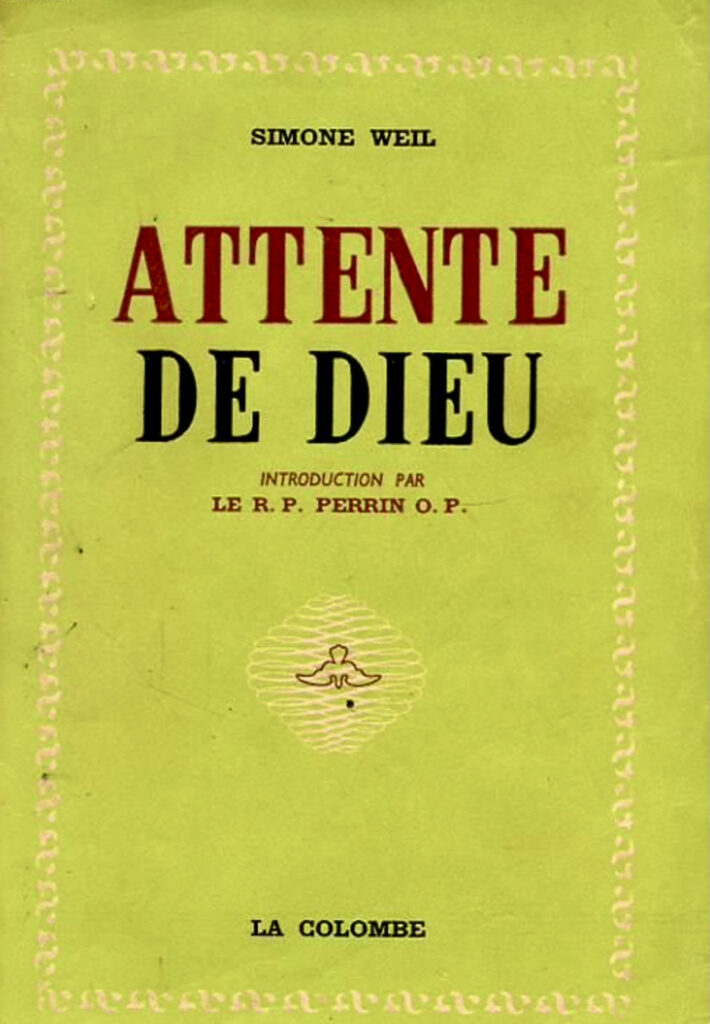

J. M. Perrin’s Preface to Attente de Dieu

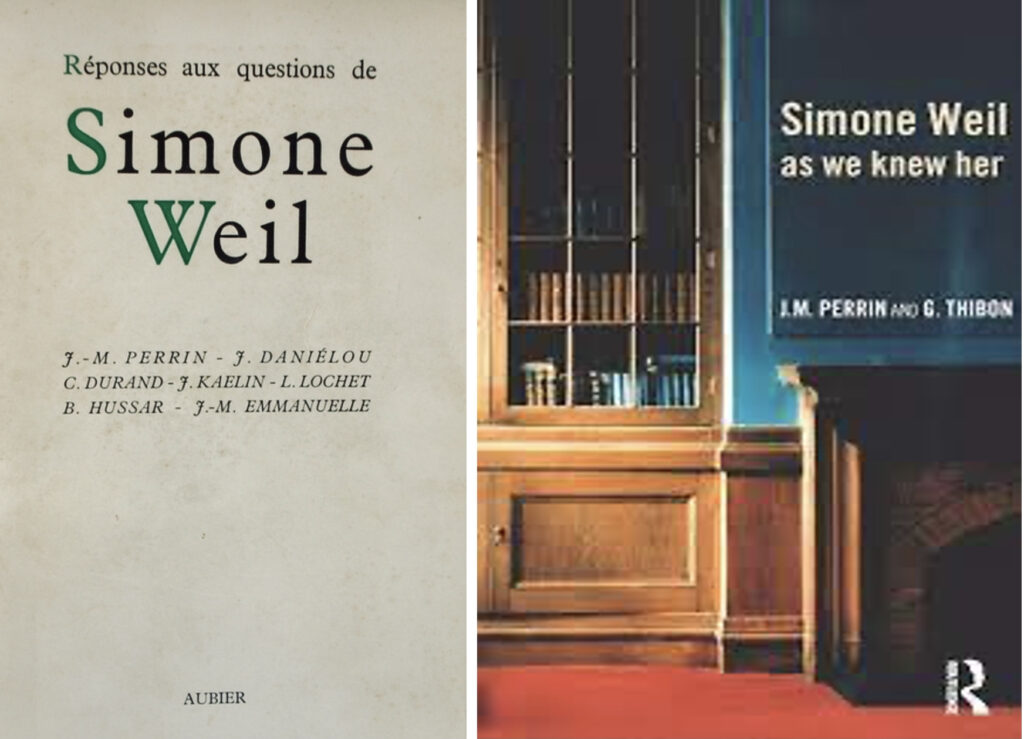

Joseph-Marie PerrinBelow is a document long lost to time, Father Joseph-Marie Perrin’s introduction to the original French publication of Attente de Dieu (Waiting for God). That Introduction appears below, translated for the first time in English by Professor Lawrence Schmidt. Professor E. Jane Doering has also written an introduction titled “A Spiritual Friendship: Simone Weil and Père Perrin.”

Preface by J. M. Perrin

These texts, gathered under the title Waiting on God, are among the most beautiful that Simone Weil left with me. They were all composed between January and June 1942; and all are related more or less closely to the dialogue that, from the preceding month of June, we engaged in together attentive to the Truth, she, drawn to Christ, I, a priest for thirty years.

In 1949, I had agreed to publish these texts and especially the correspondence – which is the most beautiful part – in order to make known the most insightful elements of her interior experience and of her personality. But the reason for this publication was special since Simone Weil had expressed explicitly the desire, at the time of our varied meetings, to give to others the possibility of entering into this dialogue. We had spoken of it often, I can assure you, and it was in this spirit that she gave me these texts and those of Intuitions Préchrétiennes. In her farewell letter to me she articulated what she was thinking: “I only want to see you get their attention. It is only you who attention I can implore in their favor. I would like the charity you have lavished on me to be diverted from me and directed towards what I am carrying in myself and which, I would like to believe, would be directed to more than me.”

I chose the title Waiting on God because it was cherished by Simone; she saw in it the vigilance of the servant awaiting the return of his master. This title also expresses her unfinished character which, because of the new spiritual discoveries that she had made, tormented Simone.

This recollection, as brief as it may be, is even more necessary since we do not have here in front of us the text when compared with the texts that are destined to be published and conceived to live in some way independent of their author. These texts on the other hand, especially the letters, are themselves, if one can express it in this way, part of herself and one cannot understand them without situating them in the context of her research, her personal development and even the dialogue in which she had been engaged.

The precociousness of her intelligence guaranteed her success in school. At the lycee Duruy she did her year of philosophy so that she could continue her education with Le Senne. At Henri IV she prepared for the competition for entry into the École normale and came under the profound influence of Alain. She was nineteen years old when she entered the École Normale and twenty-two when she passed her aggregation: 1928-1931.

Simone Weil was born in Paris on the third of February 1909. She received no religious education: “I was raised by my parents and my brother in a complete agnosticism,” she wrote to me (Letter IV). One of the dominant characteristics of her childhood was a compassionate love for the afflicted; she was about five years old when the first world war and the mentorship of a soldier helped her to discover misfortune. She wouldn’t eat a single piece of sugar so she could send everything it to those who were suffering at the front. To understand the extraordinary character of this compassion – which will be one of the dominant traits of her life – one must remember the material well-being, the largeness of breadth of mind and affection with which her parents constantly surrounded her.

During her school years, she demonstrated that she was (antitala) against those who practiced Catholicism; she was even anti-religious enough to have a falling out with a fellow student who was converting to Catholicism. She approached her life of teaching and her human relationships with a complete agnosticism, not wanting to deal with the problem of God and not being able to resolve the enigma of destiny. During this period, she got involved with the syndicalist movement and the Proletarian Revolution. From that point on she never stopped working with those movements though she never at any time joined any party. She would never speak to me of the important persons whom she had the occasion to meet or to help, nor of the role that she had to play. She knew what I thought; if a priest can think himself linked to all human progress, he should hold himself as far as possible from every political question. For her, however, it was the love of those afflicted that dominated. One of her companions in the social struggles, a young worker, told me: “She never participated in politics,” and he added: “If everyone was like her, there would no longer be any affliction.” This compassion for the afflicted is one of the essential traits of her profound life.

Le Puy was the locale of her first teaching assignment. It was there that she began to give free rein to her real communion with the misery of others. In order to have the right to claim unemployment insurance, the workers were subjected to hard labor; she saw them breaking rocks in the streets. Like them and with them, she wanted to handle the pick. She accompanied them on some protest or other to the municipal officials. In order to live, she satisfied herself with the amount equal to the daily unemployment allocation, distributing to others the surplus of her resources. On the day that she received her salary one could see at the door of the young philosophy teacher a line of her new friends. One even saw her later try hard to give generously of her time—this from time that she snatched from her passionately loved books—to play cards with some of them, to sing with others, and to make herself one of the gang.

***

However, Simone was far from feeling satisfied. In reality, who was she to love (since compassion is a torment)? In 1934 she decided to take on, with all its difficulty, the workers’ condition. She knew directly the fatigue, the rebuffs, the oppression of work on the production line, and the anxiety of unemployment. For her, it was not just an experience but a real and complete personal embodiment. Her “worker’s diary” is a poignant witness. The test was beyond her strength. Her soul was almost crushed by this knowledge of affliction; she would remain marked by it all her life.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Simone – who had largely taken part in strikes on the ground (articles of the Proletarian Revolution) – did not hesitate to take off for the Barcelonan front. An accident, caused by her awkwardness (she burnt herself with boiling oil), forced her to leave almost immediately. She scarcely mentioned this event except to bear witness to it to one or another of her fellow soldiers.

In 1938, she assisted at the holy week ceremonies at Solesmes, and a few months later she had a great illumination that changed her life: “Christ came down and took possession of me.” It is difficult to determine exactly the date of this event because she kept it a jealous secret; none of her personal papers spoke of it. It seems that none of her close friends knew of it aside from Joe Bousquet in a [12 May 1942] letter to whom she referred to it, or to myself, because she told me in words or writing. What is evident is that in the middle of the tentative elements of her research, and of the meandering of her thought, she never returned to it. In the experience of this unknown feeling, she developed an entirely new view of the world, its poetry, and its religious traditions and especially on the action in the service of the afflicted where she intensified her efforts.

Then came the war. She did not leave Paris until the capital was declared an open city. At that time she set out for Marseille. The administrative decision regarding the Jews affected her. In June 1941, she came to see me. In one of our first meetings she spoke to me of her desire to take part in the work of the farm labourers. Without difficulty, I realized that it was not a question of an unreflective idea but of a profound desire. I then asked Gustav Thibon to help her undertake this project; thus she passed several weeks in the Rhone valley and knew the hard work of harvesting grapes.

How to explain her months in Marseille? Her extreme reserve and her soulful modesty, that she concealed under the inflexible and monotone discussion of ideas, prevented her from speaking about herself or her activities. Regardless, could she remain unnoticed?

***

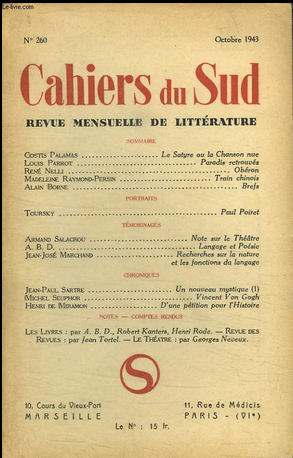

As for her literary activities, she was in contact with the contributors to the Cahiers du Sud and she wrote under the pseudonym of Emile Novis (an anagram of her name). She wrote several important articles, which notably included “The Iliad or the poem of force,” “the agony of a civilization seen through an epic poem,” “in what does the Occitanian inspiration consist,” not to mention several of her poems. More importantly, most of her time was dedicated to translations of Plato, to some Pythagorean texts which appeared under the title Intuitions Pre-chretiens, and to the composition of essays which in part constitute this book. She read these texts to some friends in intimate meetings where she dedicated herself to communicating her love of Greece and especially the realities achieved by the great mystics.

As casual readings of choice, at this time, it is rather remarkable that she was attracted to the memoirs of Cardinal Retz and D’Aubigne’s Tragiques.

Reading and writing did not fill up her life; her mind’s inclinations and the desire for compassion that characterized her could not leave her a stranger to the life of the most wretched. She sought them out and spent time with them in order to know them well and help them. She was particularly interested in the Vietnamese who had been displaced and were waiting to be repatriated; she argued about the injustice of their fate and knew how to maneuver things so that she was able to have the director of the camp dismissed.

In one situation, this love of others saved her life: arrested for Gaullism, she was interrogated for a long time and threatened with prison “where she, a graduate of philosophy, would spend time with prostitutes.” She accepted this by responding: “I have always wanted to experience this milieu, and in order to enter it I have never thought there could be another means than this: prison.” Hearing these words the judge gave a sign to his secretary that he should release her as a crazy woman!

And since we are considering her underground activity, it must be said that Simone dedicated herself to the distribution of Temoignage Chretienne; she preferred this engagement to others that existed at that time. Later, to get herself parachuted into France, she took advantage of the links which united her with the organizers of the movement; she wrote on this topic to Maurice Schumann: “I believe that by far it is the best element in France at this moment. May nothing unfortunate happen to it.”

However, her deep preoccupation was with the religious question. For a long time, she examined the Gospels, discussed them with her friends who loved to meet her at Sunday mass. Frequently, she came to see me and, to have more solitude, assisted during the week at a morning mass. At this time that she wrote to me: “My heart has been transported forever, I hope, into the Blessed Sacrament on the altar.” This spoke a lot about the living silence of our churches as it exerted such an attraction to her.

Thus the weeks and the months in Marseille passed quickly. In March 1942 I was relocated to Montpellier, but I came back often enough to see her several times before her departure. This lengthy period was the occasion of her most beautiful letters. On the 14th of May she sailed off with her parents.

When she arrived in New York, she used all her connections and her old friendships to get herself brought back to France; she threw out appeals like this: “I beg of you, bring me back to London; don’t let me despair from sadness here.” “I appeal to you to take me out of the moral quandary in which I find myself which is far too sad.” “I entreat you to get for me a number of useful sufferings and dangers, which will preserve me from being consumed with sterility by sadness. I cannot live in the situation I find myself in at this moment. That places me quite close to despair.” (to M. Schumann)

Her love of the disinherited never left her. “I explore Harlem,” she wrote to one of her friends [Dr. Louis Bercher]. “Every Sunday I go to a Baptist church where, except for me, there isn’t a single white person.” She entered into contact with black girls, invited them to her place. And the same friend who knew her well told me: “It is certain that if she had stayed in New York she would have become black.”

However, her heart was in the universe. “The affliction spread out on the surface of the earth obsesses me and crushes me to the point that it wipes out my faculties and I cannot regain them and relieve myself from this obsession which provides a large portion of danger and suffering. It is then a condition for which I have the capacity to work.” (To M. Schumann.)

London, where she arrived at the end of November, imposed a cruel deception on her. She had only one goal: to obtain a difficult and dangerous mission, to sacrifice herself usefully either to save other lives or to accomplish an act of sabotage. She asked for it aloud and insisted on it in writing. “I cannot stop myself from being ashamed, the indiscretion of beggars. Like beggars I only know how to, in the place of arguments, declare my needs.” It was an imprudent request. She thus dedicated herself to certain intellectual work. She passed many hours in her office, making do with a simple sandwich, staying there overnight when she had let the hour of the last subway train pass, sleeping with her head propped up on the table or stretched out on the ground.

When she begged with insistence to obtain [a dangerous] mission, she noted: “The effort that I make here will be in a short time stopped by a triple limit. The first is a moral limit because of the sadness of feeling myself out of my place, believing ceaselessly I will finish in spite of myself, I fear, clogging up my thought. The second limit is intellectual. It is evident that at the moment of going down to the concrete, my thought is going to be left without an object. The third limit is physical because my fatigue is increasing.”

(credit: J Cabaud, Simone Weil (1964))

The event, alas, had to prove her correct. In April she had to acknowledge the reality [of our situation] and have herself admitted to the Middlesex hospital. The care that she received could not restore her health because of the extreme weakness caused by both her fatigue and her privations. She wanted to go to the countryside thus arranged to be transferred to the sanatorium at Ashford where she died on the 24th of August 1943.

From these texts of the weeks preceding her death, it seems that she remained at a great distance from the Catholic faith in its fullness at many point. She profoundly felt that only death would transport her to the truth from which she understood herself so distant. She always fixed her attention on the points that remained obscure in order to receive the light; the large lines that dominated her life, lines that she had become aware of during the months of Marseille and which are like the depth of Attente de Dieu.

J.-M. Perrin

Translation copyright © 2022: Lawrence Schmidt. Several attempts have been made to identify the copyright holder of the French text of the Preface. Anyone having credible information concerning this should contact the editors. Hyperlinks and photographs have been added to the text.

Professor Schmidt is grateful to Eric Springsted and E. Jane Doering for their assistance in translating the preface.

Related

- Eric Springsted, “God in His Mercy: A Letter to Father J.M. Perrin, May 15, 1942,” Parabola, vol. 33, no. 2 (2008), pp. 48-56.

5 Recommendations