Simone Weil: 2023 Colloquy on Decreation, Capitalism, Ecofeminism, and Sacrifice in the Cadre of Work

E. Jane Doering

Imagine being in a spatial hall overlooking a serene garden in the center of bustling Paris along with 80 other Simone Weil enthusiasts eager to share their latest insights on the French philosopher. That was the setting for the 46th annual colloquy of the French Association pour l’Étude de la pensée de Simone Weil, which was celebrating the 80th anniversary of the philosopher’s death with the topic of « Le travail : Simone Weil en débat ». The title, designed to encourage wide exploration of the ramifications of Weil’s concept of work intertwined with spirituality, invited Weil readers and scholars to two full days of presentations. We met in the Assumptionist convent, L’Enclos Rey, now transformed into a welcoming conference center in the XVième Arrondissement. Weil scholars discussed in both practical and theoretical terms a vast array of contemporary perspectives on work as a means of confronting the real in a well-organized society.

The Colloquy’s Contents

Some topics covered were the following:

- innovations in science and technology,

- the colonization of women’s work in a capitalist economy,

- the neglect of ecology, and

- Weil’s lyrical style that transmits her sense of joy in work.

The intersection of the philosopher’s thought with the writings of other French thinkers on work, such as:

- Gilbert Simondon, who focused on technology and the individual,

- Positivist philosopher Pierre Laffitte,

- Émilie Hache, specialist in pragmatic ecology and philosophy, and

- varied international ecofeminists were explored.

An invited guest: Professor Michel Miné, an experienced advocate for workers’ rights, both French and international, and a member of the French National Conservatory of Arts and Trades, compared Simone Weil’s original concept of workers’ rights to actual and potential conditions in France, as well as in the European Union.

Living Legacy: The Little Sisters of the Assumption

An austere green metal door, almost hidden in the midst of a noisy Parisian street, leads to L’Enclos Rey. A code opens this discreet barrier to reveal a worn cobblestone path leading to the former convent dormitory, on the other side of which is an extensive green space right in the heart of the teeming metropolis. This contemplative setting, once considered outside city limits, is the mother house of the Little Sisters of the Assumption, formed in 1864 at the very beginning of industrialization, to provide succor to crowds of disoriented agricultural workers and their families seeking a livelihood in the factories. The founders of the Assumptionist congregation reacted to the rampant poverty and misery suffered by these individuals adrift from their familiar rural societies by assuming the vital mission of seeing to their human needs.

Their work among the socially vulnerable continues today through the dedication of the Little Sisters and of extensive lay groups of women. So the cadre of the gathering couldn’t have been more appropriate. While space permits only a select few of the presentations to be included here, all of the talks will be published in a forthcoming issue of the Cahiers Simone Weil, a fount of cutting-edge reflections on the religious philosophy of Simone Weil. Do your colleagues a favor by having your library subscribe to this indispensable research source.

Weil Scholars & Students

Robert Chenavier, the world’s foremost Simone Weil scholar, opened the conference with the direct question of whether discussion of the notion of work has been exhausted. With his usual probing reflections and provocative queries, he continued: What is work actually? What transforms an activity into work? Is it a skill, a profession, an employment, a livelihood? He suggested that the word “work” has no precise signifier; work is everywhere, but its essence and embodiment are nowhere. Consequently, Simone Weil’s philosophical analyses, always backed up by real concrete experience, are indispensable.

Weil perceived that the abstract concept of work, born with capitalism, generated a real and hitherto unseen oppression. By working in the factory, she supported her reflections with this vital and concrete contact with the real, consistent with her conviction that all philosophy and knowledge must be embodied in action; all spirituality must pass through the body. Simone Weil, contrary to Hegel, believed that work can contribute to the ethical grounding of individuals, and she asked what must be done to effectuate and maximize this possibility. According to Chenavier, the results of her probing, which underline the whole philosophical foundation of her religious philosophy, continue to be essential to understanding the role of work for the human being.

Professor Paul Clavier, from the Department of Philosophy at the University of Lorraine, maintains that Weil’s concept of work as the spiritual center of a well-organized society was the consistent center of gravity in all her life’s work. Her critique of Marx’s conception of work provides a useful counterpoint. Weil categorically rejects Marx’s proposition that human beings produce themselves through their work, leaving no opening for considering creation from a force beyond the material universe. Only methodical confrontation of necessity in the physical universe through a knowledge of geometry can bring a sense of liberty, according to Weil; her insight counters Marx’s prideful claim that liberty is obtained by dominating necessity. Work, to her mind, requires consistent and careful thinking, followed by judicious application of thought, which inevitably entails a daily process of dying to oneself.

Clavier highlights this ethic of self-sacrifice in work; work’s imperative for a daily decreation of self can bring a sense of freedom and open a spiritual space for receiving God’s grace. This quotidian descent into self-mortification without hope of compensation of any kind restores a balance that provides a bulwark against moral gravity ever present in human life. Professor Clavier makes an analogy of this equilibrium, achievable though the decreation of self, with that substantiated in the Cross: Christ’s self-sacrifice establishes a balance between the pull of inherent moral gravity and the counter force of grace. He concludes that Weil’s intuition on work, with its radical metaphysical and spiritual aspects, points to a source of true joy in work that comes with self-effacement rather than in self-fulfillment.

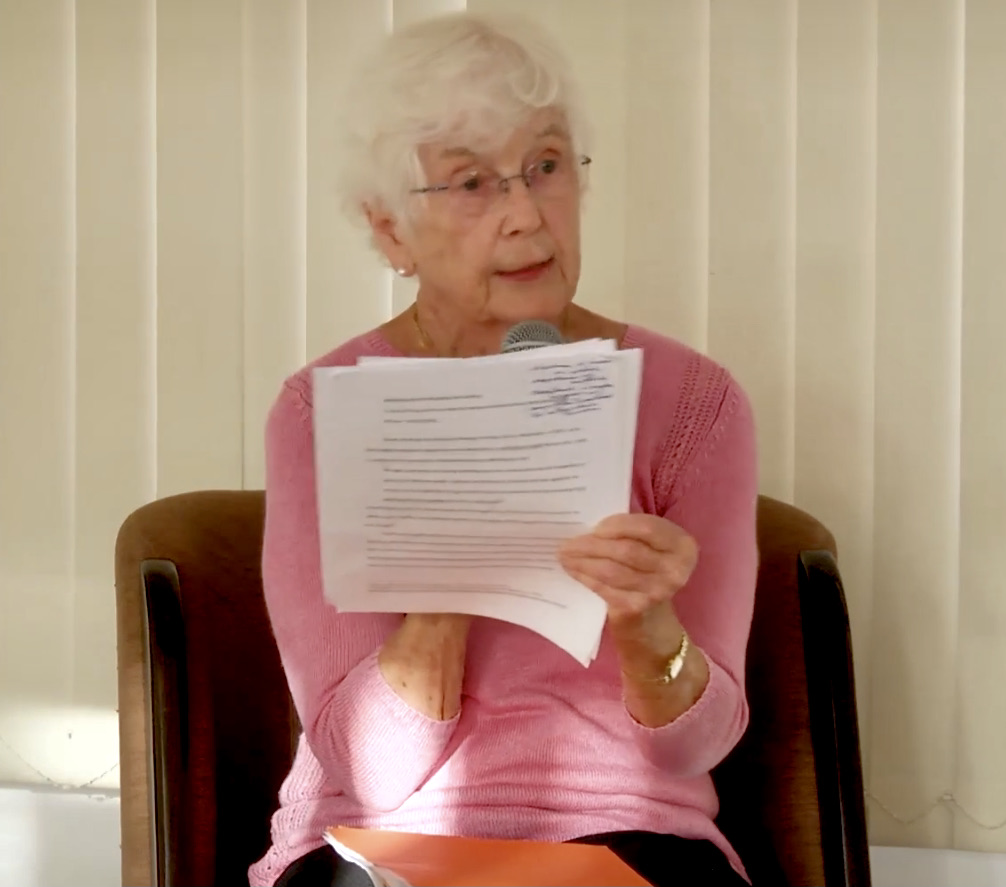

A selection of Weil’s lyric expressions of the potentiality of joy in work was collated and poetically read in the presentation, « Penser la joie au travail avec Simone Weil » by Blandine Delanoy, a student of literature and philosophy at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris. All were enthralled with her reading of a collection of citations apropos work culled from the entire corpus of Weil’s writing. One expression of moments of joy and incomparable fullness in work comes from de l’oppression in “Réflexions sur les Causes de la Liberté et Oppression: “En ces moments de joie et de plénitude incomparables on sait par éclairs que la vraie vie est là, on éprouve par tout son être que le monde existe et qu’on est au monde. » (330) (“In these moments of joy and incomparable plenitude, one knows by flashes that the true life is there, one senses throughout one’s whole being that the world exists and that one is of the world.”)

Joy also has a place in the rereading of Simone Weil from the point of view of ecofeminists who value woman’s role in the subsistence—or the sustaining—of the human race, which is par excellence a confrontation with necessity. Maÿlis Dupont, sociologist and director of experimental programs dealing with ecological and social transitions in the ESS (Economie Sociale et Solidaire), enhanced the position of subsistence feminism with Simone Weil’s claim that meeting necessity full on is not a retraction of being but rather an experience of the fullness of existence.

Addressing our time of ecological crisis, Dupont Interspersed Simone Weil’s criticism of work under the capitalist and industrialist regime with insights from a wide variety of ecofeminists, who deplore that what has been termed progress has been regression. Worldwide domination of capitalism and of the politics of development has led to the exhaustion of the earth and a diminishment of its livableness. Natural sources of energy are being exhausted, the search for new sources is expensive, and women’s ability to stem this regression has been severely limited.

Highlighting the insights of Geneviève Pruvost, sociologist of work, with whom the term ‘subsistence feminism” gained significance, and of philosopher of pragmatism Emilie Hache, among many others, Ms Dupont gives an overview of different perspectives on the current crisis from ecofeminists. Ecofeminism has its source in the cross-section of ecological struggles and of women’s endeavors to defend their role within the worldwide capitalist regime, the efforts needed to survive in it, as well as to redefine it as a means of existence. She sees harmony in the theories of Simone Weil and the ecofeminists.

Women see a juncture between the materiality of the world—viewed as necessity—and spirituality. Separating them is incomprehensible. They see the earth as a living being that guarantees their survival and that of their children. Subsistence work, that of production and reproduction of life, in caring for the aged and the sick, managing the household with all its ineluctable chores, has become alienated and degraded. Such work should be a synonym for security, a good life, liberty, autonomy, self-determination, preservation of the means of existence, economic and ecological, and a diversity of biological culture, not just based on monetary value.

Work done by women in the household, however, and by the mother of a family is made invisible, naturalized, and absent from the real conscience of industrial society. Human beings are reproduced, uniquely, thanks to work and food, thanks to care that nurtures them, and to love and tenderness. Ms. Dupont sees that feminists have much to offer in re-examining the potentialities in the inherent natural affinities of women and their bodies, particularly in this time of crisis, all of which is akin to the heartfelt quest of Simone Weil to analyze and alleviate oppression in all its forms.

In a similar vein, Robert Chenavier extends Weil’s perception of the new form of oppression seen in the workplace as not limited to that of one class oppressing the other but of purposeful domination in order to maintain the social relationship between those who command and those who obey. He claims that her analyses go beyond those of Alain and of Heidegger. Alain’s perception was limited to the pre-industrial experience, although his forward-looking view of decentralizing the workplaces had promise.

Weil’s goal of keeping the conquest of capitalism in collective and methodical work but without the oppression, differed from the theories of Heidegger, and in fact had no common measure with what one could read at that time. Material and social conditions of its actualization determine her conclusions, while Heidegger’s remained more on paper. In many ways, his focus on theoretical conjectures about work separates her thought from his, which she would probably, according to Chenavier, have categorized as illusory. Work, for her, was never glorified as a manifestation of a people’s community that would be all classes working together in harmony. Neither contemporary French nor German philosophers offered perspectives that could nourish her unique probing of the roots of oppression found in industrialized work nor her goal of elevating the position of the workers to allow them to reflect on the methods and goals in the production process.

With the very rich contributions of a dozen Weil scholars who opened up new avenues of research regarding Simone Weil and her work, the answer to Robert Chenavier’s initial question as to whether we have exhausted the topic is clearly “No.”

The full list of presenters and their topics is on the Association’s website.

Our own Emily King gave a presentation on Simone Weil and her Notebooks that was greatly appreciated. If you would like to contact any of the scholars for further discussion, please write to Marie-Noêlle Chenavier for their email address.

Next Colloquy

Better yet, brush up on your French and plan to give a presentation in the 2024 colloquy that will take place in Arles, France, on the topic of Simone Weil & Marxism. More specifics to come.

E. Jane Doering, University of Notre Dame, Indiana (Emerita), is a member of Attention’s Advisory Board.

Recommend