“Translations of Beauty: Simone Weil and literature” — the 2022 American Weil Society colloquy at the University of Notre Dame (Part I)

E. Jane Doering“Today, what would Simone Weil say of a “spiritual direction” usurped by the vilest of publications and media that impose on us a daily reading of the world?”

Robert Chenavier‘s keynote speech (March 17, 2022)

Introduction

Note: The brief summaries that follow are designed to encourage further discussion with their authors and others.

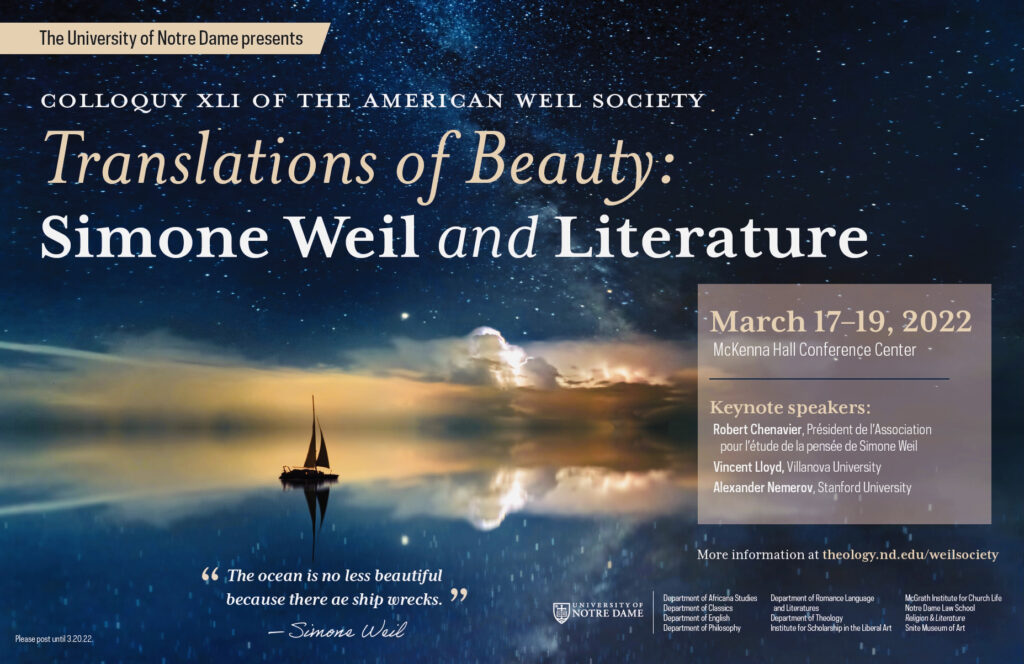

The 2022 AWS colloquy “Translations of Beauty: Simone Weil and literature” opened on the campus of the University of Notre Dame (March 17-19, 2022) welcoming close to 100 participants, virtual and in person. Robert Chenavier, editor of the Simone Weil: Oeuvres complètes (Gallimard Press, Paris) and of the quarterly Cahiers Simone Weil, set the tone by speaking on Simone Weil’s theme: “The Responsibility of Writers: The true relationship of good and evil.”

Dean Sarah Mustillo‘s gracious welcome to the American Weil Society included a heart-warming encouragement on the multi-faceted teaching of Simone Weil’s thought in the College of Arts and Letters. Since 2005, faculty in seven different departments, teaching 35 undergraduate courses, plus seven on the master’s and doctoral level, have deepened awareness of Simone Weil’s thought for close to 400 students. Present colleagues and students increased these numbers by participating in this latest colloquy.

With this reassurance that the efforts of Simone Weil scholars are not proceeding in a vacuum, we discussed two dozen papers exploring Simone Weil’s engagement with literature and its relation to truth and evil over three days, with related topics pursued on the three consecutive Fridays by Zoom. The categories of literature transmitting the beauty of Weil’s thought included biography, autobiography, autofiction, narratives, poetry, drama, and journaling. The gamut extended from ancient works: Homer’s epics, “Antigone,” and “Electra” to “King Lear” to modern poetry by George Oppen and Adrienne Rich and modern fiction by Walker Percy, Elsa Morante, and Kevin Brockmeier. All were probed for echoes of Simone Weil’s search for the truth, which needs an appropriate transmission for each point in time. Additional presentations on themes of ecology, silence, politics, Wittgenstein, and contradiction enriched our discussions.

The Significance of Silence in Literature as an Expression of Truth

An elegant atmosphere was created in the interstices of intense thinking by harp music at our opening reception, the students’ Voices of Faith Choir singing before Dr. Vincent Lloyd’s address and an engaging choral reading composed by Professor Ann Astell and read by students in her philosophy and her theology seminar, co-taught with Alexander Jech. The choral reading focused on Weil’s love of folktales that illustrate critical concepts of her religious philosophy.

Professor Robert Chenavier, a world-renowned French Simone Weil scholar, spoke on the philosopher’s idea that literature of the highest order is an expression of truth that can only be created with a proper orientation of the spirit. Writers expressing the true relationship between good and evil, applying the plenitude of attention to their object, can reveal pure values of Truth, Beauty, and Good. Mature writers, turning their attention toward the Truth and the Good, craft the conditions for the eventual “descent” of pure genius, as opposed to “demonic geniuses” who lack the perspective for a truthful expression of good as related to evil. Their ultimate recourse should be silence, which was the final choice of French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Chenavier concluded with a pertinent question: “Today, what would Simone Weil say of a “spiritual direction” usurped by the most of vile of publications and media that impose on consumers a daily reading of the world?” [video of remarks here]

Speaking from Italy, Noemi Sanchez of Paraguay developed two opposing aspects of Weil’s theme of silence: one, multi-dimensional and transcendental, that allows access to reality and the other, mono-dimensional and sourced in the worldly action of Evil, that hinders the elevation of the individual. Outlining Weil’s concept of the divine and ontological foundation of silence, Ms. Sanchez considered the ethical impact of both types of silence on social life according to Simone Weil.

Julie Daigle reflected on the meditative practice of journal writing by both Simone Weil and Henry David Thoreau, which honed their art of seeing—through attention for Weil and awareness for Thoreau—and led to political resistance. She points out that they wrote in silence, solitude, and receptiveness to their own thought, using a poetic language that added a prophetic tone, each maintaining a certain personal silence.

Ed Chan Stroud from Oxford charted a connection between affliction, beauty, and trauma, in which the “hiddenness” of the beauty of the Eucharist made manifest through love, can play a healing role for trauma-affected individuals. His reflections began with Simone Weil‘s description of how “only God, present in us, can really think the human quality unto the victims of affliction, can really look at them with a look differing from what we give to things, can listen to their voice as we listen to spoken words.” Stroud calls for a space to be made for the silenced narratives of the afflicted to be heard.

The Classics and Slavery

Mindful of the significance of silence in literature, other participants explored trauma, suffering and words not uttered in the ancient dramas “Antigone” and “Electra” as well as in “King Lear,” all works of literature ardently admired by Simone Weil. Her focus on Homer’s Iliad was a springboard for keynoter Dr. Vincent Lloyd of Villanova University, to juxtapose Weil’s two antithetical concepts of slavery; the one viewed as an external physical and psychic use of force and the other as an internal consent for full obedience to God. She condemns the former in her harsh critique of oppression in colonialization and extolls the second as the willing death of self, using the Passion as a model. Noting the use of Homer’s Odyssey in Black thought, Professor Lloyd tested Weil’s analysis of slavery against the idea of slavery as expressed in recent Black literature and incorporated into the writings of Black theologians.

Cristina Basili from Spain provided a critical perspective of Weil’s interpretation of the character of Electra, in view of Weil’s philosophical analysis of trauma, of extreme suffering and of individual and collective liberation. Thus, Basili offered evidence for Weil’s conceptual relevance for contemporary political theorists and opened new ethical and political configurations. Pascale Devette compared two philosophic interpretations of love in “Antigone;” that of Simone Weil and that of Martha Nussbaum, who considers Antigone to be cold, closed, and excessively pursuing an impersonal and single-minded passion. Weil’s reading of Antigone, on the contrary, reveals a rare and demanding form of love, which is consubstantial with her love for others and echoes her concept of an impersonal love

Lucy Grinnan chose Weil’s examples of Antigone and Joan of Arc as models of the process by which the afflicted create beauty and become sources of spiritual inspiration She sees their sacrificial openness to affliction and truth as analogous to Simone Weil’s front-line nurses and all three as models for Weil’s call for a new sainthood.

Sr. Ann Astell applied Joan Dargan’s process of “thinking poetically” to Weil’s description of King Lear as “the direct fruit of the pure spirit of love.” She argued that Weil’s sustained meditation on King Lear between 1938 and 1943 furthered her philosophical investigations of affliction, gravity, ingratitude, justice, human dignity, and speaking truth in her late writings. Weil, attending Donald Wolfit’s celebrated performance of the play in London in January 1943 while suffering over the denial of her plan for an elite corps of nurses, would have noted that both Cordelia and the Fool are named nurses in that production and that their words of wisdom are met with silence or mockery.

The poetic style

In contrast to the Ancients, two modern poets confronted each other metaphorically in Matthew Kilbane’s talk on George Oppen and Cynthia Wallace’s presentation on the poetry of Adrienne Rich. Wallace skillfully navigated Rich’s virtual love/hate engagement with the French philosopher’s thought by portraying the way Rich, simultaneously, accepted and spread Weil’s words of wisdom, yet struggled against her embrace of a cruciform Christianity. Espousing Weil’s ethics and politics in a thoroughly desacralized frame, Rich models a secular literary feminism that does justice to Weil’s provocations yet questions the philosopher-mystic’s decreative impulse. Kilbane illustrated Oppen’s poetic style of taking concepts or passages out of context, such as Weil’s image of a nail whose point is applied at the very center of the soul to dramatize the mystery of extreme affliction. Another poem of Oppen’s claims to be inspired by a phrase of Weil’s that is suggested, but never mentioned in words. Kilbane opined that the suggested phrase’s provenance might be The Need for Roots, which took on a talismanic significance for Oppen, as he struggled against the 1960s counterculture.

Spiritual friendship in biography, autobiography and autofiction

Brenna Moore and E. Jane Doering, from the Universities of Fordham and Notre Dame, gave examples of how spiritual friendship, seen as a gift stemming from God’s implicit love for his creation, can be the germinal source of fine literature both in the form of biography and of autobiography. Dr. Moore recounted the immediate and intuitive sense of Simone Weil’s profound spirituality gleaned by Marie-Magdalena Davy in their first brief meeting. Davy then transcribed Weil’s spiritual insights by writing the first biography of Weil in English and by forming an international Simone Weil house. On a parallel plane, the spiritual friendship between Simone Weil and her Dominican mentor Joseph-Marie Perrin was the causal factor in Weil’s composing her spiritual autobiography for him in epistolary form. Père Perrin included her private letters to him in the collection of “Waiting for God,” saying that he considered them among her most beautiful writings. Without this singular friendship and his deep respect for Weil’s closeness to the supernatural, no one would have had access to her unique experience with Christ expressed in Weil’s beautiful literary form.

Contrary to Weil’s epistolary expression of the spiritual impersonal within herself, sought by means of decreation, autofiction aims for the personal that transcends itself through a formal interrogation of the self, according to Peter Morgan of Harvard Law School. Since several modern novelists in the autofiction genre use Weil as a reference in their works, Morgan sees Weil as a useful subject and foil for an enriching interrogation of the genre. Similarly, Alexandra Sweny of Concordia University in Quebec chose Chris Kraus’ “cult-classic” I Love Dick to apply decreation as a literary technique to autofiction as it moves beyond the confines of the first-person narrative. Sweny maintains that Chris Kraus’ fiction is deeply indebted to and structured by Weilian thought, in particular her concept of decreation. Walker Percy’s anti-hero Lancelot is a portrayal in the most devastating terms of failed decreation and therefore a botched redemption, according to the analysis by Michael Jewell of the Colorado School of Health. In his analysis, Percy’s protagonist fills “an emptiness in [himself] by creating one in somebody else,” and thus embodies Weil’s view of emptiness and false divinity, without which one is unable to give attention and love to another.

Dino Alfier of London sees in the main protagonist of Kevin Brockmeier’s novel Illumination an incarnation of the anguish inseparable from knowledge of the simultaneous existence of affliction and of God’s love. Alfier points out the conundrum inherent in God’s withdrawal, allowing pernicious affliction to exist, and in the act of attention, which also requires withdrawal, but combined with love creates a new being. Seeking to assuage the distress, he reflects that although humans do have the knowledge, it is far from perfect knowledge.

Michela Dianetti, from the University of Rome, now in the Department of Italian Studies at the National University of Ireland, Galway, comments on the dichotomy between Weil’s idea of force turning the human being into an impersonal being and l’impersonnel approached through self-effacement. The first, resulting from destruction, and the second, from decreation, are both central in Elsa Morante’s novel La Storia, in which all human beings are equally at the mercy of chance, since no one escapes being subject to necessity.

For access to any full paper or to start a dialogue with other Weil scholars, you can find their emails through their university or inquire through the AWS website.

Part II of the AWS Colloquy Summary will take up the other presentations on questions of Justice, theology, Giotto, translation of Weil’s works, contradiction, philosophy, and ecology.

Sample Audience Responses

Below is a sampling of some of the many reactions from participants:

“Thank you for organizing such a great colloquy. Everyone was so supportive (but not uncritically so) of each other’s point of view, which is not always easy to do when so many different angles are put on the table. I felt very welcome. It was wonderful to see how relevant Weil’s thought can be in areas I never associated with her philosophy, such as gender politics, and environmental activism. Being new to Zoom, I was a little anxious about presenting virtually, but everything ran so seamlessly, and the in-person attendees were so generous in often giving precedence to the virtual attendees.”

“It was wonderful to be in person for my very first AWS conference. It was a model of hospitality and collegiality around our shared interest in the endlessly fascinating Simone Weil. Despite this singular focus, the conference was expansive in the best way. The scholars were truly international, presenting in English but working in multiple languages, and we covered a staggering range of topics including race, literature, friendship, and human rights as they relate to Simone Weil’s life and thought. It was focused yet open and energizing, and I’m so grateful to have gone! Thank you hosts!”

“I was particularly grateful for the keynote lecture by Dr. Vincent Lloyd, “Are We All Slaves? Weil, Homer, and Black Thought.” An aspect of Weil that makes her so compelling as a philosopher of social justice is her ability to say things that others may not, to push boundaries, and to creatively think beyond norms. As Weil scholars, I believe it is our responsibility to hold Weil to the same standard that she herself held others and to think through the problematic aspects of her work with attention, love, and unrelenting critique. Weil’s use of the term slave is important in this respect, and it is encouraging to see the American Weil Society pushing on these questions in her work.

E. Jane Doering is on Attention’s Advisory Board and the co-author (with Ruthann Knechel Johansen) of When Fiction and Philosophy Meet: A Conversation with Flannery O’Connor and Simone Weil (2019).

2 Recommendations